UUPC A __________________

advertisement

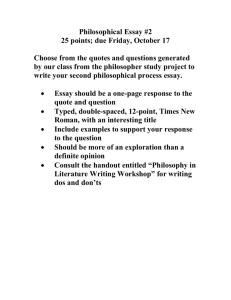

UUPC APPROVAL __________________ UFS APPROVAL ___________________ SCNS SUBMITTAL _________________ CONFIRMED ______________________ BANNER POSTED ___________________ CATALOG ________________________ Florida Atlantic University Undergraduate Programs—COURSE CHANGE REQUEST DEPARTMENT: COLLEGE: COURSE PREFIX AND NUMBER: PHI 1933 CHANGE(S) ARE TO BE EFFECTIVE (LIST TERM): CURRENT COURSE TITLE: HONORS FRESHMAN SEMINAR IN PHILOSOPHY TERMINATE COURSE (LIST FINAL ACTIVE TERM): CHANGE TITLE TO: CHANGE DESCRIPTION TO: CHANGE PREFIX FROM: TO: CHANGE COURSE NO. FROM: TO: CHANGE CREDITS FROM: TO: CHANGE GRADING FROM: TO: CHANGE WAC/GORDON RULE STATUS ADD*__X___ REMOVE ______ CHANGE PREREQUISITES/MINIMUM GRADES TO*: CHANGE COREQUISITES TO*: CHANGE GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS ADD*______ REMOVE ______ CHANGE REGISTRATION CONTROLS TO: *WAC and General Education criteria must be clearly indicated in attached syllabus. For General Education, please attach General Education Course Approval Request: *Please list existing and new pre/corequisites, specify AND or OR and www.fau.edu/deanugstudies/GeneralEdCourseApprovalReq include passing grade (default is D-). Attach syllabus for ANY changes tominimum current course information. uests.php Should the requested change(s) cause this course to overlap any other FAU courses, please list them here. Departments and/or colleges that might be affected by the change(s) must be consulted and listed here. Please attach comments from each. Faculty contact, email and complete phone number: Amy McLaughlin, amclaugh@fau.edu, (561) 799-8586 Approved by: Date: ATTACHMENT CHECKLIST Syllabus (see guidelines for requirements: www.fau.edu/academic/registrar/UUPCi nfo/) Department Chair: ________________________________ _________________ College Curriculum Chair: __________________________ _________________ College Dean: ___________________________________ _________________ UUPC Chair: ____________________________________ _________________ Syllabus checklist (recommended) Provost: ________________________________________ _________________ Written consent from all departments affected by changes WACPrograms approvalCommittee (if necessary) Email this form and syllabus to mjenning@fau.edu one week before the University Undergraduate meeting so that materials may be viewed on the UUPC website prior to the meeting. General Education approval (if FAUchange—Revised October 2011 necessary) Harriet L. Wilkes Honors College PHI 1933: Honors Perspectives on Science INSTRUCTOR Amy L. McLaughlin; phone/voice mail: 561-799-8586; email: amclaugh@fau.edu Office: HA 125; office hours: Tuesday/Thursday 1–3 pm, Wednesday 2–4 pm, and by appointment. REQUIRED TEXTS I.B. Cohen and R.S. Westfall, Newton: Texts, Background, Commentaries William Coleman, Biology in the Nineteenth Century Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species Stillman Drake (ed.), Galileo: Dialogue Concerning Two Chief World Systems Edward Grant, Physical Science in the Middle Ages John Losee, A Historical Introduction to the Philosophy of Science Richard Westfall, The Construction of Modern Science INFORMATION ON THE WEB Electronic copies of this syllabus, other class handouts, and links to other relevant sites may be obtained from the class web page, which may be accessed through MyFAU. COURSE DESCRIPTION AND OBJECTIVES The course is intended to provide students with an understanding and appreciation of the nature of science by exploring conceptual, historical, and philosophical aspects of the development of the physical and the biological sciences mainly from the early17th century to the late-19th century. The course centers around three key figures: Galileo, Newton, and Darwin. Key scientific concepts and theories developed and supported by these figures are considered in detail through their own writings. Also considered are their expressed views on central philosophical issues such as scientific method, the meaning of concepts, the structure of theories, the nature of evidence, and the existence and influence of metaphysical presuppositions. Secondary sources are used in order to explore the historical contexts in which these key figures developed and gained acceptance for their scientific ideas (contextually relevant issues include social, political, economic, and religious factors as well as writings of other key figures in science and philosophy at the time). REQUIRED WORK The course is writing intensive in nature and serves as one of two “Gordon Rule” classes at the 2000-4000 level that must be taken after completing ENC 1101 and 1102 or their equivalents. You must achieve a grade of “C” (not C-minus) or better to receive credit. Furthermore, this class meets the University-wide Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) criteria, which expect you to improve your writing over the course of the term. The University’s WAC program promotes the teaching of writing across all levels and all disciplines. Writing-to-learn activities have proven effective in developing critical thinking skills, learning discipline-specific content, and understanding and building competence in the modes of inquiry and writing for various disciplines and professions. If this class is selected to participate in the university-wide WAC assessment program, you will be required to access the online assessment server, complete the consent form and survey, and submit electronically a first and final draft of a near-end-of-term-paper. A significant portion of the work in this course requires regular attendance, class preparation, and participation in class discussions. In addition, students must submit several written assignments. In class writing exercises will be assigned as appropriate to facilitate student understanding, and there will be some short out-of-class writing assignments as well. Grades for these short writing assignments will count as part of the preparation and participation component of the grade. In addition, students must write two philosophical essays, and complete two take-home essay examinations. The exams will include essay questions that require analysis, synthesis, and reflection. As part of the examination process, each student will be required to rewrite the reflective essay on the first exam. For the first philosophical essay (7-8 pages; about 2000 words), students will be required to write a paper proposal, which will be discussed and reviewed in a class workshop devoted to aiding students in developing their paper projects. The second philosophical essay will undergo a similar process. Also, the second essay must be a revision and extension of the first, written so as to accommodate instructor’s comments and the student’s own considered reflections on the first essay. As an extension, the second essay must be 30-50% longer than the original, incorporating relevant elements of the course material covered after the first essay assignment. See the end of this syllabus for the criteria that will be used to evaluate philosophical essays. The final grade is determined according to the following weighting of assignments: Attendance, Preparation, and Participation……... 20% Essays………………………….……………….. 20% (each) Exams…..………………………………………. 20% (each) COURSE GRADING POLICIES FAUchange—Revised October 2011 Students will receive substantial feedback on all of the written assignments for which students receive a grade, in addition to feedback on many assignments during special sessions in class designated for discussing and reviewing written work. Essays and exams are graded on a 100-point scale. Any written assignments that are received after the stated deadline will be assessed steep penalties (less than 12 hrs. late = 10%, less than 24 hrs. late = 20%, etc.). A letter-grade for the course is determined by calculating the weighted average using the weights above, which is then converted to a letter grade according to the following scale: A (94-100); A– (90-93); B+ (87-89); B (84-86); B– (80-83); C+ (77-79); C (74-76); C– (70-73); D+ (67-69); D (64-66); D– (60-63); F (0-60). Borderline cases will be assigned the higher grade only if there are academically justifiable reasons for doing so. Criteria Used in Grading Philosophical Essays A Outstanding (all of the following): (i) The essay is well organized, contains no significant grammatical or spelling errors, and is written in a coherent, highly effective style. (ii) The essay provides strong evidence of a deep understanding of the relevant principles and arguments. (iii) The essay contains a powerful, insightful argument for a clear and interesting thesis. An insightful argument is one that goes beyond merely repeating points made in class, and is developed on the basis of significant insight into the author’s work. A powerful argument uses plausible and relevant premises in support of an interesting conclusion, and is clear enough so as to avoid potential reasonable misunderstandings. B Above-average (all of the following): (i) The essay is well organized, contains few significant grammatical or spelling errors, and is written in an effective style. (ii) The essay provides evidence of a significant understanding of the relevant principles and arguments. (iii) The essay contains an insightful argument for a clear and interesting thesis, but the argument is not as powerful as that in an essay deserving an A. C Average (all of the following): (i) The essay is fairly well organized, does not contain too many grammatical or spelling errors, and is written in a satisfactory style. (ii) The essay provides evidence of a fair understanding of the relevant principles and arguments under discussion, though this understanding may be rather superficial. (iii) The essay contains an argument for a relevant thesis, but the argument does little more than repeat points made in class and usually makes only a poor attempt to clarify so as to avoid misinterpretation or misunderstanding. D Inadequate (any of the following): (i) The essay is poorly organized, contains numerous spelling or grammatical errors, or is written in a weak style. (ii) The essay shows a poor understanding of the relevant principles and arguments. (iii) The essay has a poorly formulated and poorly supported thesis, or contains little to no philosophical argument. F/NC Unacceptable (any of the following): (i) The essay is poorly organized, contains numerous spelling and grammatical errors, lacks general coherence, or is very confused in its expression. (ii) The essay shows a considerable lack in understanding of the relevant principles and arguments, or dramatically misses the crux of the assignment. (iii) The essay has no clear thesis, offers little to no support for the thesis, or is guilty of plagiarism. (The minimum punishment for plagiarism is zero on the essay; the maximum punishment is expulsion from FAU.) ACADEMIC INTEGRITY/HONOR CODE Enrollment in this course constitutes agreement to abide by Florida Atlantic University’s academic integrity code (http://www.fau.edu/ctl/AcademicIntegrity.php) as well as the Honor Code of the Wilkes Honors College (http://www.fau.edu/divdept/honcol/academics_honor_code.htm). If you are uncertain what constitutes a violation of code of academic integrity or the honor code, consult with the instructor before handing in any papers. Please note that any source of ideas not your own must be acknowledged and all sources consulted must be credited – where quotations or paraphrases are used the appropriate page number or equivalent must be noted; where no quotations or paraphrases are used but the work nevertheless was consulted this usage must also be noted. FAUchange—Revised October 2011 Special Needs: Both FAU and the Honors College are committed to proving opportunities for students with special needs. Please see the university policy on the Students With Disabilities Act: http://www.osd.fau.edu/Rights.htm NOTE OF HONORS DISTINCTION: This course differs substantially from non-Honors courses in a number of ways. First, the writing component of the course is more demanding, and is designed to foster care and attention to writing as well as assisting students in preparation for upper-division college writing and for work on the Honors Thesis. Students will be exposed to vocabulary of a specifically theoretical nature, and will be expected to comprehend these new concepts and to deploy these new terms in their own critical thinking and writing. Students will be expected to not only study the philosophical and scientific literature and familiarize themselves with the history and the ongoing critical and scholarly conversations invoked in these works, but to engage philosophically themselves with the texts both in historical context and from the perspective of their current worldview. Most importantly, this course will reflect the interdisciplinary nature of Honors education and will inculcate critical attitudes and skills that will allow students to develop theoretical connections between various elements of their studies across disciplines and to forge for themselves new pathways for discovery. COURSE OUTLINE Below is a tentative schedule of readings, lectures and assignments. The actual schedule may deviate from this outline, and additional readings may be assigned as seems warranted by class discussion. The readings are the materials to be read in preparation for class on the corresponding days. Day Mon Wed Mon Wed Mon Wed Mon Wed Mon Wed Date 1/8 1/10 1/15 1/17 1/22 1/24 1/29 1/31 2/5 2/7 Readings Losee, chapters 1-5 Grant, chapters 1-3 Mon 2/12 Wed Mon Wed Mon Wed Mon Wed Mon Wed 2/14 2/19 2/21 2/26 2/28 3/5 3/7 3/12 3/14 Mon 3/19 Wed 3/21 Losee, chapters 9-9.2 and 10 Mon Wed Wed Mon 3/26 3/28 3/28 4/2 Coleman, chapters 1-3 Wed 4/4 Mon 4/9 Wed Mon 4/11 4/16 Pages Content 1-38 Aristotle through Medieval Period 1-35 500 A.D. - Medieval Period MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. HOLIDAY 36-90 Mechanics 5-41 41-85 Heavenly and Earthly Bodies 85-113 114-173 173-222 Terrestrial Mechanics 222-275 Grant, chapters 4-6 Galileo, The 1st Day Galileo, The 2nd Day PAPER WORKSHOP—bring paper proposal to class for discussion and review (First Essay due Friday, 2/16) Losee, chapters 6-8 Westfall, chapters 1-3 Westfall, chapters 4-6 Westfall, chapters 7-8 Newton, part 4 39-85 3-64 65-119 120-159 165-218 Saving Appearances, Galileo through Newton Dynamics and Mechanics Chemistry, Biology & Organization of Science Newtonian Mechanics Optics SPRING BREAK Newton, part 5 Newton, part 6 219-250 251-296 Rational Mechanics System of the World Review of Materials on Exam 1 (Exam 1 due Friday, 3/23) 86-117, 132-142 1-56 Scientific Method Biology and Organisms Rewrite of Essay from Exam 1 due Coleman, chapters 4-5 Coleman, chapters 6-7 57-117 118-166 Transformation and Human Biology Experimentation PAPER WORKSHOP—bring paper proposal to class for discussion and review (Second Essay due Saturday, 4/7) Darwin, introduction and chapter 1 Darwin, chapters 2-3 Darwin, chapters 4 and 14 FAUchange—Revised October 2011 53-100 Variation 101-129 130-172, 435- Variation and Struggle Natural Selection, Conclusion Wed 4/18 Mon 4/23 Wed 4/25 Losee, chapters 14 and 17 460 197-209, 236251 Scientific Progress & Evaluative Standards Review of Materials on Exam 2 (Exam 2 due SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Achinstein, Peter (ed.). Scientific evidence: philosophical theories and applications, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Achinstein, Peter. Particles and waves: historical essays in the philosophy of science, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. Barker, Peter and Roger Ariew (eds.). Revolution and continuity: essays in the history and philosophy of early modern science, Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1991. Ben-Chaim, Michael. Experimental philosophy and the birth of empirical science: Boyle, Locke, and Newton, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004. Berman, Morris. The reenchantment of the world, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981. Blake, Ralph M., Curt J. Ducasse and Edward H. Madden. Theories of scientific method: the Renaissance through the nineteenth century, ed. by Edward H. Madden. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1989. Campbell, Mary B. Wonder & science: imagining worlds in early modern Europe, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999. DeWitt, Richard. Worldviews: an introduction to the history and philosophy of science, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2004. Donovan, Arthur, Larry Laudan, and Rachel Laudan (eds.). Scrutinizing science: empirical studies of scientific change, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. Earman, John and John D. Norton (eds.). The cosmos of science: essays of exploration, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997. Feingold, Mordechai. The Newtonian moment: Isaac Newton and the making of modern culture, New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. Gould, Stephen Jay. The mismeasure of man, New York: W. W. Norton, 1981. Grant, Edward. Much ado about nothing: theories of space and vacuum from the Middle Ages to the scientific revolution, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981. Henry, John. The scientific revolution and the origins of modern science, New York: Palgrave, 2001. Hesse, Mary B. Revolutions and reconstructions in the philosophy of science, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980. Keller, Evelyn Fox. Reflections on gender and science, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985. Krüger, Lorenz.. Why does history matter to philosophy and the sciences? ed. by Thomas Sturm, Wolfgang Carl, and Lorraine Daston. New York: De Gruyter, 2005. Kuhn, Thomas S. The Essential tension: selected studies in scientific tradition and change, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977. Latour, Bruno. We have never been modern, trans. by Catherine Porter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. Lloyd, G. E. R. Magic, reason, and experience, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979. Machamer, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge companion to Galileo, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Machamer, Peter K. and Robert G. Turnbull (eds.). Studies in perception: interrelations in the history of philosophy and science, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1978. Machamer, Peter, Marcello Pera, and Aristedes Baltas (eds.). Scientific controversies: philosophical and historical perspectives, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Mandelbaum, Maurice. Philosophy, history, and the sciences: selected critical essays, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984. Margolis, Howard. Paradigms & barriers: how habits of mind govern scientific beliefs, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. North, J.D. and J.J. Roche (eds.). The Light of nature: essays in the history and philosophy of science presented to A.C. Crombie, Hingham, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1985. Pomper, Philip and David Gary Shaw (eds.). The return of science: evolution, history, and theory, Lanham, MD: Roman & Littlefield, 2002. Rickert, Heinrich. The limits of concept formation in natural science: a logical introduction to the historical sciences, ed. and trans. by Guy Oakes. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Strong, Edward W. Procedures and metaphysics: a study in the philosophy of mathematical-physical science in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Merrick, NY: Richwood Pub. Co., [1976] 1936. Wilson, Catherine. The invisible world: early modern philosophy and the invention of the microscope, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995. Wilson, Fred. The logic and methodology of science in early modern thought: seven studies, Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1999. Zinsser, Judith P. (ed.). Men, women, and the birthing of modern science, DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2005. FAUchange—Revised October 2011