THE JEANNE CLERY ACT COMPLIANCE, COLLABORATION AND TRAINING Martha M. Walters

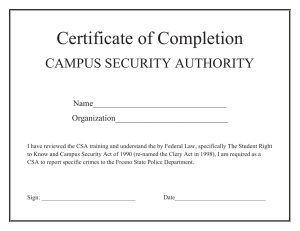

advertisement