Research on Violence, Resistance, Safety and Prevention

advertisement

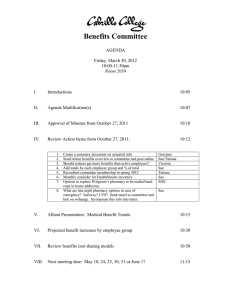

Research on Violence, Resistance, Safety and Prevention McGill Centre for Research on Children and Families Catherine Richardson/Kinewesquao, Ph.D University of Montreal Centre for Response-Based Practice December 2, 2015 My Background -Metis with Dene, Cree & Gwichin ancestry -Raised on Coast Salish territory, Vancouver Island -A counsellor/family therapist, anti-violence worker -Professor Univ. de Montreal, Social Work -Mother of three teenagers -Co-director Centre for Response-Based Practice & Network of Spiritual Progressives, Quebec Overview of Research Involvement -CIHR Promoting Health Through Collaborative Engagement with Youth in Canada: Overcoming, Resisting & Preventing Structural Violence. -mixed race Indigenous arts-based PAR youth group in Montreal (with Dr. Elizabeth Fast) -street-involved Trans/gender fluid arts-based PAR youth group in Vancouver with RainCity Housing -SSHRC Metis well-being after experiences of child welfare in Canada (book in progress) -Metis identity… The Relationship Between Cultural Stories and the Sense of Self (book in progress) -Member of RIV – Responses to Interpersonal Violence Network -Islands of Safety I worked, for over a decade, with Metis Community Services on Vancouver Island, 1995 - 2011 In 2011, 451,795 people identified as Métis in Canada. They represented 32.3% of the total Aboriginal population and 1.4% of the total Canadian population. 4 -We begin with a shared analysis of violence, resistance, responses & accurate language and social context. -”Just because people have problems doesn’t mean there is something wrong with them/us.” (A Wade) History & Evolution of the RB Ideas • Systemic thinking…. The problem is not situated in the person, it is between people, in the social world • People appreciate fairness, justice and situating their experience in context • Feminist contributions, an analysis of power imbalances • Social justice • Human agency as part of human dignity Four Operations of Language Work Together To Benefit Perpetrators & the Status Quo Conceal Violence Blame, Pathologize Victim Obscure Responsibility Conceal Resistance The Four Operations of Language in Response-Based Practice Reveal the Violence & Oppression Contest Clarify The Blaming of Responsibility Victims Clarify Resistance • Resistance is a response to, not an effect of . . . • Interviewing methods for elucidating and honouring individuals’ responses and resistance to violence and oppression • Distinction between responses and effects (stories of resistance or stories of pathology/illness) • Applies to social interaction in general, and to forms of adversity other than violence Response-Based Contextual Analysis S. Bonnah, L. Coates, C. Richardson, A. Wade (2014) Social Material Conditions Responses to Social Responses Situation Interaction Social Responses Offender Actions Victim Responses & Resistance Making clear the war on women! 12 Understanding Victim Resistance Those darn socks Boot laces Scrubbing the floor – leaving the corner undone Account 1: Contrasting Accounts of Male to Female Violence Sue and Tom had been dating for five weeks. One night they had an argument on the way home from the pub. Tom complained that Sue was cold and not interested in sex. Tom stopped to urinate in the bushes and asked Sue to stop and wait. He caught up to Sue at Sue's apartment. Tom wanted to come in. He pushed the door open and forced his way in. Tom pushed Sue hard against the wall, called her a nasty name, and punched a hole in the wall inches from her face. Tom grabbed Sue and punched her in the ribs, twice. Tom kicked her in the ribs, then left the apartment. Account 2: Contrasting Accounts of Male to Female Violence Sue and Tom had been dating for five weeks. One night they had an argument on the way home from the pub. Sue complained that Tom was rude and drank too much. Tom complained that Sue was cold and not interested in sex. When Tom stopped to urinate in the bushes, Sue kept walking. Tom asked Sue to stop and wait, but she refused. By the time Tom caught up to Sue, they were at Sue's apartment. Sue told Tom he could go to his own place, but Tom wanted to come in. Sue insisted that he go to his own place. He pushed the door open and forced his way in. Sue told him to get out. Tom pushed Sue hard against the wall, called her a nasty name, and punched the wall inches from her face. Sue ducked underneath his arm and ran for the phone in the living room. Tom grabbed Sue and punched her in the ribs, twice. Sue rolled onto her side, gasping for breath. Tom kicked her in the ribs, then left the apartment. Sue found the phone and called her best friend. Social Responses to Victims and Offenders How family, friends, professionals, and larger society (media, police, child protection, courts) respond when violence is disclosed. A majority of victims report receiving negative social responses Examples: What does “positive” and “negative” mean? Family, Friends, Police, Court, Child Protection Marginalized, disadvantaged people are more likely to receive negative social responses: LGBTQ, Aboriginal, Refugee, Disabled The quality of social responses may be the best single predictor of the level of victim distress Victims’ Responses to Social Responses Victims respond physically (epigenetically, hormonally), emotionally, mentally, socially, spiritually – to positive and negative social responses Victims who receive POSITIVE social responses: - tend to recover more quickly and fully - are more likely to work with authorities - are more likely to report violence in future Victims who receive NEGATIVE social responses: - less likely to cooperate with authorities - less likely to disclose violence again - more likely to receive diagnosis of mental disorder How to stop violence • Provide positive social responses upon disclosure, responses that…. – Stop the violence – Make the person safe – Let the person know they are valued and worthy of care – Show them that violence is not a viable social tool The Islands of Safety Team Cathy & Allan Cheryle Henry Family Therapists The 19 Team Members Jeff Smith Music therapist Audrey Chartrand SW Grant writer Erica Briggs Researcher Islands of Safety is…. -An orchestrated positive social response to victims of violence -An intervention for Metis & Urban Aboriginal families referred to the Ministry for reasons of violence -An Indigenous systemic-family therapy, feminist-informed, dignity-centered safety planning process -Committed to including dads, extended family & mothers with a focus on maternal Child Welfare & Legislation • The model is used in accordance with the British Columbia Child and Family Services Act, Section 15, Mediation, Traditional Dispute Resolution • Fits with recent shifts to a Collaborative Practice mandate • Referrals come from the Ministry of Children and Family Development child protection workers or Aboriginal agencies Consultation Process • Phase One involved a process of community consultations with mothers, fathers, social workers, agency workers, advocates, family group conference facilitators, administrators, cultural teachers, elders • Metis elder Maria Campbell shared Cree and Metis teachings, that form the central theme, layers of blankets representing “Islands of Safety” , a metaphor depicting the creation of safe spaces in a violent culture. Dignity • Focuses on what we already know, believe think and do • Allows maximize freedom in appointments, topics of discussion • Always asks permission, renegotiates each time • Makes the spirit of safety explicit • Treats people as responsible, choice-makers, acting with deliberation 24 Dignity involves…. • • • • • • Manners Social protocols Avoiding humiliation in all encounters Repairing social harm & embarrassment Daily acts of kindness & caring A collective response to humiliation Dignity Through Attending to Language • Contesting the Colonial Code of Relations, Decolonization • Contesting the Parallel Objectifying Practices • Reversing the Four Operations • Awareness of embedded pre-suppositions & Avoiding Advice-giving • Talking about responses to acknowledge the activity, action and agency of the individual and contest accusations and diagnoses of passivity. Structure - Four Stages 1. Agency referral 2. Preparation & pre - planning meeting 3. The “Islands of Safety” meeting - a one day process (with similarities to FGC, but with an accentuated attention to safety where there has been violence) 4. Follow up meeting Safety Criteria • The perpetrator has demonstrated . .. – that no immediate threat exists, as evidenced by others and those who have been harmed – a willingness to discuss the specific aspects of the violent behaviour – responsibility for the violent actions, acknowledged the actions as wrong, apologized to those harmed & taken steps to restore safety and recovery for the victim – a desire to become accountable, via a counsellor or third party – a desire to participate in child safety planning and contribute to child safety The Safety Conference The Safety Conference Introduction to the Day Round One Round Two Round Three Round Four Private Family Safety Planning Time Closing the Meeting Follow Up Meeting • Held approximately three weeks after the initial meeting • Communication team attends, consisting of the mother/non-offending parent, a facilitator, the child protection worker • Assess ongoing community supports to ensure family safety • Plan for closing the file Interviewing For Accurate Accounts Identification Responses & Resistance to Event Possible Change Social Responses To Event & To Family Responses to Social Responses Event Dignity Dignity Safety Dignity 39 Islands of Safety is an orchestrated positive social response to violence & a means to restoring dignity. Thank you for listening! UNIVERSITÉ DE MONTRÉAL wwww.responsebasedpractice.com cathyresponds@gmail.com