Perl Major parts of this lecture adapted from 26-Jul-16

advertisement

Perl

Major parts of this lecture adapted from

http://www.scs.leeds.ac.uk/Perl/start.html

26-Jul-16

Why Perl?

Perl is built around regular expressions

REs are good for string processing

Therefore Perl is a good scripting language

Perl is especially popular for CGI scripts

Perl makes full use of the power of UNIX

Short Perl programs can be very short

“Perl is designed to make the easy jobs easy, without

making the difficult jobs impossible.” -- Larry Wall,

Programming Perl

2

Why not Perl?

Perl is very UNIX-oriented

Perl does not scale well to large programs

Perl is available on other platforms...

...but isn’t always fully implemented there

However, Perl is often the best way to get some UNIX

capabilities on less capable platforms

Weak subroutines, heavy use of global variables

Perl’s syntax is not particularly appealing

3

What is a scripting language?

Operating systems can do many things

copy, move, create, delete, compare files

execute programs, including compilers

schedule activities, monitor processes, etc.

A command-line interface gives you access to these

functions, but only one at a time

A scripting language is a “wrapper” language that

integrates OS functions

4

Major scripting languages

UNIX has sh, Perl

Macintosh has AppleScript, Frontier

Windows has no major scripting languages

probably due to the weaknesses of DOS

Generic scripting languages include:

Perl (most popular)

Tcl (easiest for beginners)

Python (new, Java-like, best for large programs)

5

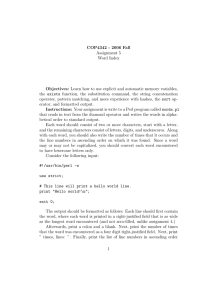

Perl Example 1

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

#

# Program to do the obvious

#

print 'Hello world.';

# Print a message

6

Comments on “Hello, World”

Comments are # to end of line

But the first line, #!/usr/local/bin/perl, tells where to find

the Perl compiler on your system

Perl statements end with semicolons

Perl is case-sensitive

Perl is compiled and run in a single operation

7

Perl Example 2

#!/ex2/usr/bin/perl

# Remove blank lines from a file

# Usage: singlespace < oldfile > newfile

while ($line = <STDIN>) {

if ($line eq "\n") { next; }

print "$line";

}

8

More Perl notes

On the UNIX command line;

In Perl, <STDIN> is the input file, <STDOUT> is the output file

Scalar variables start with $

Scalar variables hold strings or numbers, and they are

interchangeable

Examples:

< filename means to get input from this file

> filename means to send output to this file

$priority = 9;

$priority = '9';

Array variables start with @

9

Perl Example 3

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

# Usage: fixm <filenames>

# Replace \r with \n -- replaces input files

foreach $file (@ARGV) {

print "Processing $file\n";

if (-e "fixm_temp") { die "*** File fixm_temp already exists!\n"; }

if (! -e $file) { die "*** No such file: $file!\n"; }

open DOIT, "| tr \'\\015' \'\\012' < $file > fixm_temp"

or die "*** Can't: tr '\015' '\012' < $infile > $outfile\n";

close DOIT;

open DOIT, "| mv -f fixm_temp $file"

or die "*** Can't: mv -f fixm_temp $file\n";

close DOIT;

}

10

Comments on example 3

In # Usage: fixm <filenames>, the angle brackets just

mean to supply a list of file names here

In UNIX text editors, the \r (carriage return) character

usually shows up as ^M (hence the name fixm_temp)

The UNIX command tr '\015' '\012' replaces all \015

characters (\r) with \012 (\n) characters

The format of the open and close commands is:

open fileHandle, fileName

close fileHandle, fileName

says: Take input from

$file, pipe it to the tr command, put the output on

"| tr \'\\015' \'\\012' < $file > fixm_temp"

fixm_temp

11

Arithmetic in Perl

$a = 1 + 2;

$a = 3 - 4;

$a = 5 * 6;

$a = 7 / 8;

$a = 9 ** 10;

$a = 5 % 2;

++$a;

$a++;

--$a;

$a--;

# Add 1 and 2 and store in $a

# Subtract 4 from 3 and store in $a

# Multiply 5 and 6

# Divide 7 by 8 to give 0.875

# Nine to the power of 10, that is, 910

# Remainder of 5 divided by 2

# Increment $a and then return it

# Return $a and then increment it

# Decrement $a and then return it

# Return $a and then decrement it

12

String and assignment operators

$a = $b . $c; # Concatenate $b and $c

$a = $b x $c; # $b repeated $c times

$a = $b;

$a += $b;

$a -= $b;

$a .= $b;

# Assign $b to $a

# Add $b to $a

# Subtract $b from $a

# Append $b onto $a

13

Single and double quotes

$a = 'apples';

$b = 'bananas';

print $a . ' and ' . $b;

print '$a and $b';

prints: apples and bananas

prints: $a and $b

print "$a and $b";

prints: apples and bananas

14

Arrays

@food = ("apples", "bananas", "cherries");

But…

print $food[1];

@morefood = ("meat", @food);

prints "bananas"

@morefood ==

("meat", "apples", "bananas", "cherries");

($a, $b, $c) = (5, 10, 20);

15

push and pop

push adds one or more things to the end of a list

pop removes and returns the last element

push (@food, "eggs", "bread");

push returns the new length of the list

$sandwich = pop(@food);

$len = @food; # $len gets length of @food

$#food # returns index of last element

16

foreach

# Visit each item in turn and call it $morsel

foreach $morsel (@food)

{

print "$morsel\n";

print "Yum yum\n";

}

17

Tests

“Zero” is false. This includes:

0, '0', "0", '', ""

Anything not false is true

Use == and != for numbers, eq and ne for strings

&&, ||, and ! are and, or, and not, respectively.

18

for loops

for loops are just as in C or Java

for ($i = 0; $i < 10; ++$i)

{

print "$i\n";

}

19

while loops

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

print "Password? ";

$a = <STDIN>;

chop $a;

# Remove the newline at end

while ($a ne "fred")

{

print "sorry. Again? ";

$a = <STDIN>;

chop $a;

}

20

do..while and do..until loops

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

do

{

print "Password? ";

$a = <STDIN>;

chop $a;

}

while ($a ne "fred");

21

if statements

if ($a)

{

print "The string is not empty\n";

}

else

{

print "The string is empty\n";

22

if - elsif statements

if (!$a)

{ print "The string is empty\n"; }

elsif (length($a) == 1)

{ print "The string has one character\n"; }

elsif (length($a) == 2)

{ print "The string has two characters\n"; }

else

{ print "The string has many characters\n"; }

23

Why Perl?

Two factors make Perl important:

Pattern matching/string manipulation

Based on regular expressions (REs)

REs are similar in power to those in Formal Languages…

…but have many convenience features

Ability to execute UNIX commands

Less useful outside a UNIX environment

24

Basic pattern matching

$sentence =~ /the/

$sentence = "The dog bites.";

if ($sentence =~ /the/) # is false

True if $sentence contains "the"

…because Perl is case-sensitive

!~ is "does not contain"

25

RE special characters

.

# Any single character except a newline

^

# The beginning of the line or string

$

# The end of the line or string

*

# Zero or more of the last character

+

# One or more of the last character

?

# Zero or one of the last character

26

RE examples

^.*$

# matches the entire string

hi.*bye

# matches from "hi" to "bye" inclusive

x +y

# matches x, one or more blanks, and y

^Dear

# matches "Dear" only at beginning

bags?

# matches "bag" or "bags"

hiss+

# matches "hiss", "hisss", "hissss", etc.

27

Square brackets

[qjk]

# Either q or j or k

[^qjk]

# Neither q nor j nor k

[a-z]

# Anything from a to z inclusive

[^a-z]

# No lower case letters

[a-zA-Z] # Any letter

[a-z]+

# Any non-zero sequence of

# lower case letters

28

More examples

[aeiou]+

# matches one or more vowels

[^aeiou]+ # matches one or more nonvowels

[0-9]+

# matches an unsigned integer

[0-9A-F]

# matches a single hex digit

[a-zA-Z]

# matches any letter

[a-zA-Z0-9_]+ # matches identifiers

29

More special characters

\n

\t

\w

\W

\d

\D

\s

\S

\b

\B

# A newline

# A tab

# Any alphanumeric; same as [a-zA-Z0-9_]

# Any non-word char; same as [^a-zA-Z0-9_]

# Any digit. The same as [0-9]

# Any non-digit. The same as [^0-9]

# Any whitespace character

# Any non-whitespace character

# A word boundary, outside [] only

# No word boundary

30

Quoting special characters

\|

\[

\)

\*

\^

\/

\\

# Vertical bar

# An open square bracket

# A closing parenthesis

# An asterisk

# A carat symbol

# A slash

# A backslash

31

Alternatives and parentheses

jelly|cream # Either jelly or cream

(eg|le)gs

# Either eggs or legs

(da)+

# Either da or dada or

# dadada or...

32

Substitution

=~ is a test, as in: $sentence =~ /the/

!~ is the negated test, as in:

$sentence !~ /the/

=~ is also used for replacement, as in:

$sentence =~ /london/London/

This is an expression, whose value is the number of

substitutions made (0 or 1)

33

The $_ variable

Often we want to process one string repeatedly

The $_ variable holds the current string

If a subject is omitted, $_ is assumed

Hence, the following are equivalent:

if ($sentence =~ /under/) …

$_ = $sentence; if (/under/) ...

34

Global substitutions

s/london/London/

s/london/London/g

substitutes London for the first occurrence of london in $_

substitutes London for each occurrence of london in $_

The value of a substitution expression is the number of

substitutions actually made

35

Case-insensitive substitutions

s/london/London/i

case-insensitive substitution; will replace london, LONDON,

London, LoNDoN, etc.

You can combine global substitution with caseinsensitive substitution

s/london/London/gi

36

Remembering patterns

Any part of the pattern enclosed in parentheses is

assigned to the special variables $1, $2, $3, …, $9

Numbers are assigned according to the left (opening)

parentheses

"The moon is high" =~ /The (.*) is (.*)/

Afterwards, $1 = "moon" and $2 = "high"

37

Dynamic matching

During the match, an early part of the match that is

tentatively assigned to $1, $2, etc. can be referred to by

\1, \2, etc.

Example:

\b.+\b matches a single word

/(\b.+\b) \1/ matches repeated words

"Now is the the time" =~ /(\b.+\b) \1/

Afterwards, $1 = "the"

38

tr

tr does character-by-character translation

tr returns the number of substitutions made

$sentence =~ tr/abc/edf/;

$count = ($sentence =~ tr/*/*/);

replaces a with e, b with d, c with f

counts asterisks

tr/a-z/A-Z/;

converts to all uppercase

39

split

split breaks a string into parts

$info = "Caine:Michael:Actor:14, Leafy Drive";

@personal = split(/:/, $info);

@personal =

("Caine", "Michael", "Actor", "14, Leafy Drive");

40

Associative arrays

Associative arrays allow lookup by name rather than by

index

Associative array names begin with %

Example:

%fruit = ("apples", "red", "bananas", "yellow", "cherries",

"red");

Now, $fruit{"bananas"} returns "yellow"

Note: braces, not parentheses

41

Associative Arrays II

Can be converted to normal arrays:

@food = %fruit;

You cannot index an associative array, but you can use

the keys and values functions:

foreach $f (keys %fruit)

{

print ("The color of $f is " .

$fruit{$f} . "\n");

}

42

Associative Arrays III

The function each gets key-value pairs

while (($f, $c) = each(%fruit))

{

print "$f is $c\n";

}

43

Calling subroutines

Assume you have a subroutine printargs that just prints

out its arguments

Subroutine calls:

&printargs("perly", "king");

Prints: "perly king"

&printargs("frog", "and", "toad");

Prints: "frog and toad"

44

Defining subroutines

Here's the definition of printargs:

sub printargs

{ print "@_\n"; }

Where are the parameters?

Parameters are put in the array @_ which has nothing to

do with $_

45

Returning a result

The value of a subroutine is the value of the last

expression that was evaluated

sub maximum

{

if ($_[0] > $_[1])

{ $_[0]; }

else

{ $_[1]; }

}

$biggest = &maximum(37, 24);

46

Local variables

@_ is local to the subroutine, and…

…so are $_[0], $_[1], $_[2], …

local creates local variables

47

Example subroutine

sub inside

{

local($a, $b);

($a, $b) = ($_[0], $_[1]);

$a =~ s/ //g;

$b =~ s/ //g;

($a =~ /$b/ || $b =~ /$a/);

}

&inside("lemon", "dole money");

# Make local variables

# Assign values

# Strip spaces from

#

local variables

# Is $b inside $a

#

or $a inside $b?

# true

48

Perl V

There are only a few differences between Perl 4 and

Perl 5

Perl 5 has modules

Perl 5 modules can be treated as classes

Perl 5 has “auto” variables

49

The End

50