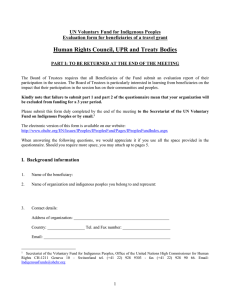

HR/GENEVA/TSIP/SEM/2003/BP.10

advertisement