Document 17702874

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

‘G

OOD

P

RACTICES

’

RELATED TO

A

CCESS TO

S

AFE

D

RINKING

W

ATER AND

S

ANITATION

Questionnaire

February, 2010

Geneva

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

Introduction

The Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation, Ms. Catarina de Albuquerque, has been mandated by the

Human Rights Council in 2008 to:

Further clarify the content of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation;

Make recommendations that could help the realization of the Millennium

Development Goals (MDG), and particularly of the Goal 7;

Prepare a compendium of good practices related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

While the work of human rights bodies has often focused on the violations of human rights, the Independent Expert welcomes the opportunity to identify good practices that address the question of how human rights obligations related to sanitation and water can be implemented.

Methodology of the Good Practices consultation process

In a first step, the Independent Expert undertook to determine criteria for identifying ‘good practices’. As ‘good’ is a subjective notion, it seemed critical to first elaborate criteria against which to judge a practice from a human rights perspective, and then apply the same criteria to all practices under consideration. Such criteria for the identification of good practices were discussed with various stakeholders at a workshop convened by the Independent Expert in

Lisbon in October 2009. The outcome was the definition of 10 criteria, 5 of which are normative criteria ( availability, accessibility, quality/safety, affordability, acceptability ), and 5 are cross-cutting ones ( non-discrimination, participation, accountability, impact, sustainability, ). The Independent Expert and the stakeholders started testing the criteria, but believe that the process of criteria testing is an ongoing one: the criteria should prove their relevance as stakeholders suggest examples of good practices.

After this consultation and the consolidation of the criteria, the Independent Expert wants to use these to identify good practices across all levels and sectors of society. To that end, she will organize stakeholder consultations with governments, civil society organisations, national human rights institutions, development cooperation agencies, the private sector, UN agencies, and perhaps others. By bringing people from the same sector together to talk about good practices related to human rights, water and sanitation, she hopes to facilitate exchange of these good practices. In order to prepare the consultations through the identification of potential good practices, the present questionnaire has been elaborated. The consultations will be held in 2010 and 2011. Based on the answers to this questionnaire, and the stakeholder consultations, the Independent Expert will prepare a report on good practices, to be presented to the Human Rights Council in 2011.

The Good Practices Questionnaire

The questionnaire is structured following the normative and cross-cutting criteria, mentioned above; hence the Independent Expert is looking for good practices in the fields of sanitation and water from a human rights perspective.

Therefore, the proposed practices do not only have to be judged ‘good’ in light of at least one normative criterion depending on their relevance to the practice in question ( availability, accessibility, quality/safety, affordability, acceptability), but also in view of all the cross-cutting criteria (non-discrimination,

2

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

participation, accountability, impact, sustainability). At a minimum, the practice should not undermine or contradict any of the criteria.

Explanatory note: Criteria

Criteria 1-5: Normative criteria (availability, accessibility, quality/safety, affordability, acceptability). All these criteria have to be met for the full realization of the human rights to sanitation and water, but a good practice can be a specific measure focussing on one of the normative criterion, and not necessarily a comprehensive approach aiming at the full realization of the human rights. Hence, not all the criteria are always important for a given practice. E.g., a pro-poor tariff structure can be judged very good in terms of the affordability criterion, whilst the quality-criterion would be less relevant in the context of determining whether that measure should be considered a good practice.

Criteria 6-10: Cross-cutting criteria (non-discrimination, participation, accountability, impact, sustainability). In order to be a good practice from a human rights perspective, all of these five criteria have to be met to some degree, and at the very least, the practice must not undermine or contradict these criteria. E.g., a substantial effort to extend access to water to an entire population, but which perpetuates prohibited forms of discrimination by providing separate taps for the majority population and for a marginalized or excluded group, could not be considered a good practice from a human rights perspective.

Actors

In order to compile the most critical and interesting examples of good practices in the field of sanitation and water from a human rights perspective, the Independent Expert would like to take into consideration practices carried out by a wide field of actors , such as States, regional and municipal authorities, public and private providers, regulators, civil society organisations, the private sector, national human rights institutions, bilateral development agencies, and international organisations .

Practices

The Independent Expert has a broad understanding of the term “practice”, encompassing both policy and implementation: Good practice can thus cover diverse practices as, e.g., legislation ( international, regional, national and sub-national ), policies, objectives, strategies, institutional frameworks, projects, programmes, campaigns, planning and coordination procedures, forms of cooperation, subsidies, financing mechanisms, tariff structures, regulation, operators’ contracts, etc . Any activity that enhances people’s enjoyment of human rights in the fields of sanitation and water or understanding of the rights and obligations (without compromising the basic human rights principles) can be considered a good practice.

The Independent Expert is interested to learn about practices which advance the realization of human rights as they relate to safe drinking water and sanitation. She has explicitly decided to focus on “good” practices rather than “best” practices, in order to appreciate the fact that ensuring full enjoyment of human rights can be a process of taking steps, always in a positive direction. The practices submitted in response to this questionnaire may not yet have reached their ideal goal of universal access to safe, affordable and acceptable sanitation and drinking water, but sharing the steps in the process towards various aspects of that goal is an important contribution to the Independent Expert’s work.

3

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

Please describe a good practice from a human rights perspective that you know well in the field of

drinking water; and/or

sanitation

Please relate the described practice to the ten defined criteria. An explanatory note is provided for each of the criteria.

Description of the practice:

Name of the practice:

Revitalisation of the Rhine through the Rhine Action Programme 1987-2000 (RAP)

From a Human Rights Perspective

Aim of the practice:

In the 1970s the Rhine was considered as one of the most polluted rivers in Europe. In these years particular the German industry along the Rhine and the few restrictions on the discharges of toxins in the Rhine water were the major source of water pollution in the river. In the 1980s the oxygen content of the river was far too low to support the growth of any organism. To this situation the fire at the

Santoz plant in Switzerland, in the mid-eighties, had disastrous consequences for the Rhine.

Thousands of litres of toxic chemicals flow into the river and caused a massive death of fish between

Basel and Koblenz.

Water intake for drinking water from the Rhine was stopped right down to the

Netherlands. No less than forty water supply plants along the Rhine had to stop their intake of water.

The toxic chemicals that flown into the river were marked with a red colour, which discoloured the river. This red colour, even though non toxic, was perceived as an outward sign of the poisoning of the river and caused an extreme public concern. After this public outcry, politicians from all the Rhine countries agreed that action had to be taken to revitalize the Rhine. Also Germany took an active role in the realization of these considerations. Commissioned by the governments of the six Rhine countries designed the International Commission for the protection of the Rhine (ICPR) a plan aimed at saving the river. The result was the Rhine Action Programme 1987-2000 ( RAP). In 2001 the Rhine 2020 1 , the programme of the sustainable Development of the Rhine, followed the Rhine Action Programme.

The Rhine Action Programme 1987 was a non binding multilateral approach between the Rhine countries:

Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, Germany and the Netherlands.

2 Difficulties with the implementation of the

1963 Rhine Convention were one of the reasons to adopt the non-binding Rhine action Programme 1987. The

Convention against Chemical Pollution and the Convention against Pollution , both signed in 1976, already provided enough legal binding for the implementation of the Rhine Action Programme, which made that a binding approach was not needed and could be even contra productive. (M. Köppel Explaining the effectiveness of Binding and nonbinding Agreements tentative Lessons from Transboundary Water pollution , 2009, Page 10)

Only in 1999 the intentions of the Rhine Action Programme were converted in a binding Convention, namely the

Convention on the Protection of the Rhine, 12/04/1999, Berne.

3 The contracting parties of this Convention were the European Community, France, Germany, Luxemburg, Netherlands and Switzerland.

Main aims of the Rhine Action Programme 1987 were to guarantee safe drinking water being available for more than 20 million inhabitants of the Rhineland and to improve the water quality of the Rhine.(Frijters and

Leentvaar, Rhine Case Study, Water Management Inspectorate, Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water

Management, the Netherlands, page 11) Another objective of the Rhine Action programme was that the water

1

Conference of Rhine Ministers 2001, Rhine 2020, Program on the sustainable development of the Rhine, www.iksr.org ( June 2010)

2 Aktionsprogramm’’Rhein’’ Internationale Kommission zum Schutze des Rheins gegen Verunreinigung. Straßburg, 30 September, 1987,

Phone interview with Mr Wieringa IKSR, June 15, 2010.

3 http://ec.europa.eu/world/agreements/prepareCreateTreatiesWorkspace/treatiesGeneralData, June 2010

4

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

of the Rhine after the implementation of the programme had to be of such a quality that the Salmon, which is very sensitive for pollution, could survive in the river.

4

These aims should be worked out through improving the quality of the ecosystem of the river and by reducing the pollution of the water by hazardous substances. The discharge of the most important substances (heavy metals, nitrogen and pesticides) should be cut by 50 % in the year 2000 compared with 1985. Harmful substances in the Rhine water endanger the drinking water production. Especially children, older people, and persons with disabilities could be harmed because of these hazardous substances in drinking water.

Another important action that should be taken to better the quality of the Rhine water was the tightening of safety and ecological norms in industrial plants alongside the river. (Frijters and Leentvaar, page 28) Particular norms were needed for the vast German industrial area’s the Ruhr and the Main. Important industrial plants along the German part of the Rhine are: Dynamite Nobel, Aluminium-Hütte, BASF, Hoechst, Bayer and

Unilever. Although the core aim to guarantee safe drinking water maintained, new aims were formulated during the project, mainly because of the Programme successes. During the implementation of the project the ecological aims of the programme became of greater importance.

Target group(s):

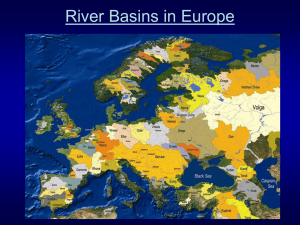

The Rhine is one of the longest (1233 km) and most important rivers in Europe. The River flows through six

European countries on its way from its source in Switzerland, to the North Sea. These countries are Switzerland,

Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, France and the Netherlands. But only in Germany and the Netherlands people get drinking water from the Rhine. Nevertheless became 20 million people in these two countries there drinking water from the Rhine.

Approximately two thirds of the river flows through Germany. Which makes also that the Rhine is not only the longest river in Germany but also its most important river. Approximately twenty percent of all chemical companies in Western Europe are located in the Rhine area. The chemical industry plays a key role in the Rhine

Action Programme, without their active role, it was not possible to revitalize the Rhine water in such an order that the river water was again useable for drinking water for many people.

4 Aktionsprogramm’’Rhein’’ Internationale Kommission zum Schutze des Rheins gegen Verunreinigung. Straßburg, 30 September, 1987,

Phone interview with Mr Wieringa IKSR, June 15, 2010, page 7

5

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

Partners involved:

The Rhine Action Programme was signed by the following countries: France, Germany, Luxembourg,

Netherlands and Switzerland and later by the European Community. The Rhine Action Programme was implemented and monitored by the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine. (ICPR). Other important partners for the implementation of the Rhine Action Plan were the chemical industry and the water supply companies along the river. Also Non Governmental Organisations took part in the programme in their role as external experts .

Duration of practice:

The Rhine Action Programme has been realized between 1987 and 2000 and found a following up in the Rhine

2020 Programme.

5 In the years 1987-2000 the core aim of the Rhine Action Programme was to improve the water quality and to guarantee the availability of safe drinking water for around 20 million inhabitants in

Germany and the Netherlands.

6 Although this core aim never changed, new aims were formulated during the project, because of the Programme's successes.

The Rhine Action Programme can be split up in four phases.

7 In phase 1 (1987-89), the International Committee for the protection of the Rhine (ICPR) made a list of priority substances like: heavy metals, nitrogen and pesticides. These priority substances were a great threat for the human health situation and the ecological system of the Rhineland. The ICPR also made an inventory of the source and amount of inputs and submitted proposals for their reduction. In phase 2 (until 1995), the priority substances were to be reduced by 50 per cent, and for some heavy metals even by 70 per cent. In Phase 3 (until 2000) additional measures and lateral plans like the

Flood Plan were to be implemented. Phase 4 focused on the (2000-2020) implementation of the follow up plan

Rhine 2020 (see also the criteria of sustainability)

Financing (short/medium/long term):

It is difficult to give an accurate picture of the costs incurred in implementing the program. If we take a look at

Germany, giving a realistic estimation of the total cost is difficult because of the fact that the German municipalities were directly responsible for the implementation of the Rhine policies instead of any federal umbrella organisation. The costs for the activities of the ICPR commission are shared by the participating countries. In order to finance the programme, 3 million Euro had been paid by every single member country.

Also Germany has paid at least 3 million Euro to cover the German part of the action programme. Also the EU invested 3 million Euro. To better the water quality of the Rhine the involved governments have built during the last 25 years waste water plants alongside the Rhine at a cost of 50 billion euro. (Upstream, Outcomes of the

Rhine Action Programme, ICPR, 2003) The Chemical plant Sandoz paid 250.000 Euro to cover some of the damage that was made during the Sandoz accident. Every member country bears also the costs of its representatives in the Commission for the protection of the Rhine (ICPR), as well as for the costs for research projects carried out in its territory.

Brief outline of the practice:

The Rhine is Europe’s most densely navigated shipping route, connecting the world’s largest seaport, Rotterdam, with the world largest inland port, Duisburg.

8 Approximately twenty percent of all chemical companies in

Western Europe is located in the Rhine area. Especially the German Ruhr and Main Areas are known for their vast industrial complexes along the Rhine.

5

http://www.iksr.org/ June 2010

6

Single data from the Rhine water production in Germany are not known to the Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wasserwerke im

Rheingebiet and the German section of the International Commission for the protection of the Rhine (ICPR)

7 Aktionsprogramm’’Rhein’’ Internationale Kommission zum Schutze des Rheins gegen Verunreinigung. Straßburg, 30 September, 1987,

Phone interview with Mr Wieringa IKSR, June 15, 2010, page 3 and 4)

8

http://www.top010.nl/html/grootste_haven_rotterdam.htm June 2010,

6

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

The water of the Rhine is used for industrial and agricultural purposes, for energy generation, for the disposal of municipal waste water, for recreational activities, and for the production of drinking water for more than 20 million people.

9 As we have seen, this intensive use of the river has caused in the 1970s and 1980s an extensive pollution of the Rhine, for which only through transnational co-operation between the Rhine countries a solution like the Rhine action Programme could be found. (Frijters and Leentvaar, Rhine Case Study, Water Management

Inspectorate, Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water Management, the Netherlands, page 3).

1. How does the practice meet the criterion of availability?

Explanatory note: Availability

Availability refers to sufficient quantities, reliability and the continuity of supply. Water must be continuously available in a sufficient quantity for meeting personal and domestic requirements of drinking and personal hygiene as well as further personal and domestic uses such as cooking and food preparation, dish and laundry washing and cleaning. Individual requirements for water consumption vary, for instance due to level of activity, personal and health conditions or climatic and geographic conditions. There must also exist sufficient number of sanitation facilities (with associated services) within, or in the immediate vicinity, of each household, health or educational institution, public institution and place, and the workplace. There must be a sufficient number of sanitation facilities to ensure that waiting times are not unreasonably long.

Answer:

Public water supply and sanitation in Germany today is universal, of good quality and continuous. In general water is not scarce in Germany, except for occasional localized dryness. Public water utilities abstract only 3 % of the total German water resource. (Branchebild 2008/Profile of the German Water Industry 2008, page 8) After the Sandoz accident in 1986, 40 water supply plants had to stop their water intake from the Rhine. By that time

Rhine water was not available for drinking water because of the extreme pollution of the River. Since the Rhine

Action Programme has been implemented the quality of the drinking water in the Rhine region, has considerably been improved through the tightening of safety norms of the chemical Industry.

10 Particularly the improvement of regulations in the German Main and Ruhr area has lead to a spectacular increasing amount of hazardous substances in the German Rhine water. Only 15 years after the implementation of the Rhine Action Programme

Rhine water was again available for the use of Drinking water.

11

2. How does the practice meet the criterion of Accessibility?

Explanatory note: Accessibility

Sanitation and water facilities must be physically accessible for everyone within, or in the immediate vicinity, of each household, health or educational institution, public institution and the workplace. The distance to the water source has been found to have a strong impact on the quantity of water collected. The amount of water collected will vary depending on the terrain, the capacity of the person collecting the water (children, older people, and persons with disabilities may take longer), and other factors. There must be a sufficient number of sanitation and water facilities with associated services to ensure that collection and waiting times are not unreasonably long.

Physical accessibility to sanitation facilities must be reliable at day and night, ideally within the home, including for people with special needs. The location of public sanitation and water facilities must ensure minimal risks to the physical security of users.

Answer:

Access to safe water and adequate sanitation in Germany is universal. Germany is one of the two countries that take water from the Rhine for drinking water purpose. In total 20 million people become their drinking water from the Rhine. The German constitution, or basic law, contains a catalogue of basic and human rights.

However, the basic law in both countries does not explicitly recognize the right to water per se. Nonetheless, the human right to water is indirectly acknowledged as part of the constitutions. (Human Rights and Access to Water

Comments by the Federal Republic of Germany pursuant to op. 1 of Decision 2/104, of the United Nations

Human Right Council, Berlin 4 th May 2007, page 3) Article 3 of the German basic law provides equal access to all state-run systems and facilities. All public water systems should be accessible on a non-discriminatory basis.

9 http://www.iksr.org/ June 2010, http://webworld.unesco.org/water/wwap/pccp/cd/pdf/case_studies/rhine2.pdf page 3

10

Upstream, Outcomes of the Rhine Action Programme, ICPR, 2003, page 4, 6

11

Upstream, Outcomes of the Rhine Action Programme, ICPR, 2003, page 22, 24

7

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

Figures from the German water supply industry show that the Water and Sanitation coverage in Germany is

100% even for the people who live in the rural areas. More than 99 per cents of the users are connected to a public water system.

12

Water supply and sanitation in Germany are the responsibilities of municipalities, carried out by water service providers of which there were more than 12,000 in 2008. (Branchebild 2008/Profile of the German Water

Industry 2008) Smaller municipalities often associate in municipal associations to secure water supply in their region. Municipalities or municipal associations in turn can delegate these responsibilities to municipal companies, private companies or public-private partnerships. (Branchebild 2008/Profile of the German Water

Industry 2008, page 13) Unlike public water supply, sanitation is considered a sovereign core responsibility of

German municipalities.

3. How does the practice meet the criterion of affordability?

Explanatory note: Affordability

Access to sanitation and water facilities and services must be accessible at a price that is affordable for all people. Paying for services, including construction, cleaning, emptying and maintenance of facilities, as well as treatment and disposal of faecal matter, must not limit people’s capacity to acquire other basic goods and services, including food, housing, health and education guaranteed by other human rights. Accordingly, affordability can be estimated by considering the financial means that have to be reserved for the fulfilment of other basic needs and purposes and the means that are available to pay for water and sanitation services.

Charges for services can vary according to type of connection and household income as long as they are affordable. Only for those who are genuinely unable to pay for sanitation and water through their own means, the

State is obliged to ensure the provision of services free of charge (e.g. through social tariffs or cross-subsidies).

When water disconnections due to inability to pay are carried out, it must be ensured that individuals still have at least access to minimum essential levels of water. Likewise, when water-borne sanitation is used, water disconnections must not result in denying access to sanitation.

Answer:

There is no regulation for water supply in Germany at the federal level. That is why the

German States (or Länder) play a key role in the water supply sector by setting the legal framework for tariff approvals. Water tariffs in Germany can differ from state to state, depending on the pricing of the different

(private, public or mixed ownership) providers. To guarantee a high quality of drinking water, the German drinking water regulation has made standards for the permitted amount of substances in the water.

13 This is another reason why the prize for drinking water in the Rhine area can differ.

The water prices in Germany are relatively high compared to other European countries.

14 The average Germany household water bill was nevertheless only 82 Euro per year, because of the low water consumption.

15 This makes that, although the water prices in Germany are relative high, water is affordable for most of its citizens.

The social assistance systems in Germany ensure that water supply and sanitation nowadays is affordable for poorer or marginalized groups of the German society.

16

In this context, it is important to note that the recent developments in Germany show that more and more commercial public utilities are created, including water supply services. To date, 3, 5 % of the water supply providers in Germany are entirely privately owned. Around 30 %of the water supply utilities are provide by municipalities. Most water supply utilities in Germany are under both private and public (mixed) ownership.

(Branchenbild BDEW 2008, page 13) Currenta GMBH & Co in Leverkussen, Germany is one of the first entirely private water supply providers in the German Rhine area, run for 60% by Bayer Industry Services

GmbH & Co and for 40% by Lanxess AG. In the case of Currenta GMBH & Co water prices are largely dependent on the market.

12 http://www.dvgw.de/fileadmin/dvgw/wasser/organisation/branchenbild2008_en.pdf

13 Verband Kommunale Unternehmen. Kommunale Wasserwirtschaft, Frage und Antworten Wasserpreise.page 2

14 http://www.unesco.org/water/wwap/facts_figures/valuing_water.shtml, June 2010

15

Unesco Report "Water for People – Water for Life" and Recommendations for Further Reports by the Federal Association of the German

Gas and Water Industries (Bundesverband der deutschen Gas- und Wasserwirtschaft - BGW) Berlin and Brussels http://www.dvgw.de/fileadmin/dvgw/wasser/organisation/branchenbild2008_en.pdf, Verband Kommunale Unternehmen. Kommunale

Wasserwirtschaft, Frage und Antworten Wasserpreise.page 2

16

Human Rights and Access to Water comments by the Federal Republic of Germany pursuant to op. 1 of Decision 2/104 of the United

Nations Human rights Council.

8

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

4. How does the practice meet the criterion of quality/safety?

Explanatory note: Quality/Safety

Sanitation facilities must be hygienically safe to use, which means that they must effectively prevent human, animal and insect contact with human excreta. They must also be technically safe and take into account the safety needs of peoples with disabilities, as well as of children. Sanitation facilities must further ensure access to safe water and soap for hand-washing. They must allow for anal and genital cleansing as well as menstrual hygiene, and provide mechanisms for the hygienic disposal of sanitary towels, tampons and other menstrual products. Regular maintenance and cleaning (such as emptying of pits or other places that collect human excreta) are essential for ensuring the sustainability of sanitation facilities and continued access. Manual emptying of pit latrines is considered to be unsafe and should be avoided.

Water must be of such a quality that it does not pose a threat to human health. Transmission of water-borne diseases via contaminated water must be avoided.

Answer:

Several federal laws secure the quality of the German drinking water.

17 In the German drinking water regulation the permitted amount of substances in the water is laid down.

18 To guarantee a high quality of drinking water the

German water quality is under permanent control. With the Rhine action Programme also the Rhine got under permanent control.

The Rhine is nowadays one of Europe’s cleanest rivers. Not only the percentage of hazardous substances in the water has been reduced by 70 to 100, but also the risk of new factory accidents and pollution accidents has decreased by implementing the Warning and Alarm Plan Rhine (WAP). The ICPR and the CHR jointly developed this alarm model for the Rhine in 1990, as mandated by the eighth Rhine ministers’ conference.

When nowadays, in spite of all preventive measures, an accident occurs or great amounts of hazardous substances flow into the Rhine, which could harm the ecosystem of the Rhine or reduce the quality of drinking water, the international Warning and Alarming Plan Rhine will be activated. With the calculations of this model the location conditions of the (initial) pollution, the decomposition and the drift capacity of the hazardous substance can be measured. The progress time of harmful substances can be forecast with an accuracy of about

89 percent. Concentration calculations have an accuracy of about 95 %. (Frijters and Leentvaar, Rhine Case

Study, Water Management Inspectorate, Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water Management, the

Netherlands, page 11) With the WAP model not only water supply companies along the river are able to prepare actions during emergency situations much better then before but also chemical plants are able to respond in a better way in case of an emergency.

In case of an accident, the warning centre concerned sends a “first report” to all centres downstream. Normally, this report is classified as “information” only. A “warning” is only produced when water quality is seriously threatened, so that the centres more downstream are able to take preventive action as rapidly as possible in order to prevent – or at least limit – expected damage. (Frijters and Leentvaar, Rhine Case Study, Water Management

Inspectorate, Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water Management, the Netherlands, page 11)

The number of WAP warnings has decreased during the 80s and the 90s, comparing with the 70s and were in the

80s and 90s constant with 12 ‘information reports’ and one ‘serious warning’ every year.

19 (ICPR, Warn- und

Alarmplan Rhein Messages 2008, Report NR.176)

A good example of how the Warning and Alarming System could estimate accidents is the Bimmen case. In

March 2008, the international Warning and Alarm Service noticed that a substantial load of dichlorobenzene was flown from the waterfront into the Rhine in the surrounding of Bimmen/Kleve, Germany. Although the substance was toxic, it could directly be determined as relatively harmless for the human health situation, because of the dilatation by the water. (ICPR, Warn- und Alarmplan Rhine Messages 2008 Report NR.176)

This example shows that with the implementation of the Warning and Alarming Plan better and faster estimates could be made of the possible danger of discharges in the river water. The Warning and Alarming system show that in most cases there is no danger for human health situation so that no action needs to be taken. In the cases that the river is seriously polluted, the hazardous substances could fast and exactly be measured, and locally the water supply could directly be stopped.

17 Human Rights and Access to Water comments by the Federal Republic of Germany pursuant to op. 1 of Decision 2/104 of the United

Nations Human rights Council, page 11)

18

Verband Kommunale Unternehmen. Kommunale Wasserwirtschaft, Frage und Antworten Wasserpreise.page 2

19

After 2003 the number of reports raised particularly trough the improvement of the technologists’ equipment for pollution measuring.

9

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

5. How does the practice meet the criterion of acceptability?

Explanatory note: Acceptability

Water and sanitation facilities and services must be culturally and socially acceptable. Depending on the culture, acceptability can often require privacy, as well as separate facilities for women and men in public places, and for girls and boys in schools. Facilities will need to accommodate common hygiene practices in specific cultures, such as for anal and genital cleansing. And women’s toilets need to accommodate menstruation needs.

In regard to water, apart from safety, water should also be of an acceptable colour, odour and taste. These features indirectly link to water safety as they encourage the consumption from safe sources instead of sources that might provide water that is of a more acceptable taste or colour, but of unsafe quality.

Answer:

Since there was great public pressure to find a solution for the polluted river water of the Rhine in the 1980s, the

Rhine Action Programme 1987 could count on broad public acceptance. To show their anger after the Santoz accident in 1987, people organised demonstrations on every bridge of the Rhine. The public outcry made that governments needed to respond to the call to revitalize the river as soon as possible. In order to produce clean water for the use of the people living in the area. It was more difficult to gain trust of the public, that the Rhine water quality had been improved extremely during the implementation of the action programme.

To show the improvement of the water quality on 14 September 1988, the German federal environment minister

Klaus Töpfer (CDU) jumped into the Rhine near Mainz to convince the public of the positive results of his Rhine policy. Not only the acceptation of the public was important to achieve the objectives of the programme, also the willingness of chemical plants along the river to cooperate with the German government was very important. In response to the fire at the Sandoz factory, the German Chemical Industry Association (Deutsche Verband der

Chemischen Industrie) made already the first steps for a review of the security in the German chemical Industry mid-November 1986. ( 20 Jahre nach Sandoz, Rhein Ökowunder, 13. Internationale Jahrestagung des

Rheinkollegs eV ) This review led to different actions by the Chemical Industry in Germany. In cooperation with the ICPR, the most important industrial plants along the river were actively involved in the reduction of discharges that could harm the human health situation. Today people in the Rhine area are dinking the water without any bias. Drinking water from the Rhine has the same quality as in other German areas.

6. How does the practice ensure non-discrimination?

Explanatory note: Non-discrimination

Non-discrimination is central to human rights. Discrimination on prohibited grounds including race, colour, sex, age, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, physical or mental disability, health status or any other civil, political, social or other status must be avoided, both in law and in practice.

In order to address existing discrimination, positive targeted measures may have to be adopted. In this regard, human rights require a focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to exclusion and discrimination.

Individuals and groups that have been identified as potentially vulnerable or marginalized include: women, children, inhabitants of (remote) rural and deprived urban areas as well as other people living in poverty, refugees and IDPs, minority groups, indigenous groups, nomadic and traveller communities, elderly people, persons living with disabilities, persons living with HIV/AIDS or affected by other health conditions, people living in water scarce-regions and sanitation workers amongst others.

Answer:

Article 3 of the German Basic Law provides equal access to all state-run systems and facilities. From this article it follows that all public water systems have to be accessible on a non-discriminatory basis. The actual responsibility for water supply in Germany lies with the municipalities, regulated by the states (Länder). Like in other EU countries, most of the German water sector standards are based on the EU Water Policy (2000/60/EC).

In the German Rhine area there are 25 water supply companies that provide drinking water. According to the

Managing director of the Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wasserwerke im Rheineinzugsgebiet ,

Wiesbaden is an example of a city that extracts water 'directly' from the Rhine. More than 25 % of the inhabitants of this city get their drink water 'direct' from the Rhine. (Der Spiegel Nr. 47/1986) Other water supply companies in the Rhine area provide drinking water for example through the use of bank filtration.

There is no regulation of water supply in Germany at the federal level. That is why German States (or Länder) play a key role in the water supply sector by setting the legal framework for tariff approvals. Water tariffs in

10

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

Germany differ from state to state, depending on the pricing by the different (private, public or mix ownership) providers. In general, commercial providers of water will be more inclined to increase their water price than public providers.

7. How does the practice ensure active, free and meaningful participation?

Explanatory note: Participation

Processes related to planning, design, construction, maintenance and monitoring of sanitation and water services should be participatory. This requires a genuine opportunity to freely express demands and concerns and influence decisions. Also, it is crucial to include representatives of all concerned individuals, groups and communities in participatory processes.

To allow for participation in that sense, transparency and access to information is essential. To reach people and actually provide accessible information, multiple channels of information have to be used. Moreover, capacity development and training may be required – because only when existing legislation and policies are understood, can they be utilised, challenged or transformed.

Answer:

Because the water of the Rhine flows through so many countries the revitalization of the Rhine needed a cross border approach and a cross border coordinator. That is why the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) was asked to coordinate the implementation and the monitoring of the Rhine Action Plan.

However, the actual implementation and funding of the measurements are in the responsibility of each of the involved states. This means that the ICPR itself is only a negotiation platform and an adviser to the Rhine governments. (Frijters and Leentvaar, page 8)

In practice this means that the environment ministers and officials from each member state take part in ICPR meetings on a regular basis. The most recently Minister conference found place in Bonn at 14 October 2007.

(Rhein-Ministerkonferenz, Bonn, 2007, MIN07-02d) The task of the ICPR is to draw up environmental projects for the Rhine, but if adopted they are funded and implemented by each member country.

An important aspect of the implementation of the Rhine Action Programme was public participation and public transparency. During the implementation of the programme the ICPR has organized conferences and published reports about the outcomes and progression of the programme. Since the early 1990s, river commissions from the region, like the Central Commission for the Rhine Navigation, the Moselle and Sarre Commission, the Lake

Constance Commission, and even the Elbe Commission (the Elbe is not directly linked with the Rhine) have had observer status at the Plenary Assembly and the meeting of the ministers of the ICPR. (www.iksr.org) Nongovernmental organizations were invited too to participate in the meetings of the ICPR. The coordination group decides on which recognized NGOs and external experts are invited for meetings of the Plenary Assembly.

(Frijters and Leentvaar, page 23)

Since 1998, NGOs can also participate in the working groups as observers or as external experts.

20 Some working groups have held preparatory meetings before the official meeting, in which NGOs participated. Each member state is totally free to organize national preparatory meetings with NGOs or other forms of public participation on Rhine issues.

20

Unfortunately the ICPR website does not give information for Germany about the different NGO’s who take part in the German meetings.

11

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

8. How does the practice ensure accountability?

Explanatory note: Accountability

The realisation of human rights requires responsive and accountable institutions, a clear designation of responsibilities and coordination between different entities involved. As for the participation of rights-holders, capacity development and training is essential for institutions. Furthermore, while the State has the primary obligation to guarantee human rights, the numerous other actors in the water and sanitation sector also should have accountability mechanisms. In addition to participation and access to information mentioned above, communities should be able to participate in monitoring and evaluation as part of ensuring accountability.

In cases of violations – be it by States or non-State actors –, States have to provide accessible and effective judicial or other appropriate remedies at both national and international levels. Victims of violations should be entitled to adequate reparation, including restitution, compensation, satisfaction and/or guarantees of nonrepetition.

Human rights also serve as a valuable advocacy tool in using more informal accountability mechanisms, be it lobbying, advocacy, public campaigns and political mobilization, also by using the press and other media.

Answer:

As mentioned before, the ICPR fulfilled not only the role of coordinator of the Rhine Action Programme but also monitors the measures taken by the individual member of the programme. The monitoring of implementations of the programme by the Rhine countries is extremely important for the transparency of the Rhine Action

Programme. In line with the Convention on the Protection of the Rhine, 12/04/1999 Berne, (see also the criteria about sustainability) the Rhine countries report regularly to the ICPR, which legislative, regulatory and other measures they have taken in order to the protection of the Rhine. Also the revealing of the monitoring reports at the website of the ICPR is part of the transparency policy of the ICPR. The drinking water quality for the Rhine

Action Programme in Germany has been monitored by the public health departments of municipalities and counties (Landkreis) and by the specific water supply companies.

9. What is the impact of the practice?

Explanatory note: Impact

Good practices – e.g. laws, policies, programmes, campaigns and/or subsidies - should demonstrate a positive and tangible impact. It is therefore relevant to examine the degree to which practices result in better enjoyment of human rights, empowerment of rights-holders and accountability of duty bearers. This criterion aims at capturing the impact of practices and the progress achieved in the fulfilment of human rights obligations related to sanitation and water.

Answer:

The water quality of the Rhine, and in a lager extent the drinking water quality, has been considerable improved in the last thirty years. Through the Rhine Action Programme a reduction in pollution by nitrates and phosphorus in the water and other types of pollution have been realised (reduces by 80 to 100%). (Upstream, Outcomes of the Rhine Action Programme, ICPR, 2003, Rhein-Ministerkonferenz, Bonn, 2007, MIN07-02d) This means that the water from the Rhine could be used again for drinking water supply.

In particular the discharges of hazardous substances by municipalities and industry have been reduced distinctly.

Many experts thought these targets could never be reached in such a short time, but ICPR samples showed that from 1985 to 1992, mercury in the river at the German town of Bimmen-Lobith, Germany near the Dutch border, fell from six to 3.2 tons, cadmium from nine to 5.9 tons, zinc from 3,600 to 1,900 tons, atrasine from 10 to 3.7 tons and PCBs from 390 to 90 kilograms.

21 The ICPR achieved these objectives through the adoption of the

“best available technology” (BAT) for the most important industrial branches along the river. Much result is also due to the annexe of new waste water treatment plants. The percentage of municipalities and industrial plants connected to waste water treatment plants rose from 85 % to 95% during the RAP. It also made provision for limiting water pollution stemming from the transportation of goods on the river.

Another good sign for the improvement of the water quality is the significant increase of the oxygen content in the Rhine, which makes it possible for small animals and bacteria to survive in the water. The improvement of the oxygen level was the start of the ecological rehabilitation of the Rhine, and with success. Already in 1997,

21

The UNESCO Courier, Vol.53, 6, 2000, page 9-12 , and, Upstream, Outcomes of the Rhine Action Programme, ICPR, 2003

12

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

three years ahead of the RAP schedule, Salmon returned to the Rhine. But not only have the Salmon benefited from the programme. Today, 63 fish species are living in the Rhine, which means that, apart from the still missing sturgeon, the former fish fauna of the Rhine has been re-established. (Upstream, Outcomes of the Rhine

Action Programme, ICPR, 2003)

The improvement of the Rhine water quality has made it again possible that a large part of the German population (directly or indirectly) drink water from the Rhine that is clean, safe and payable.

10. Is the practice sustainable?

Explanatory note: Sustainability

The human rights obligations related to water and sanitation have to be met in a sustainable manner. This means good practices have to be economically, environmentally and socially sustainable. The achieved impact must be continuous and long-lasting. For instance, accessibility has to be ensured on a continuous basis by adequate maintenance of facilities. Likewise, financing has to be sustainable. In particular, when third parties such as

NGOs or development agencies provide funding for initial investments, ongoing financing needs for operation and maintenance have to met for instance by communities or local governments. Furthermore, it is important to take into account the impact of interventions on the enjoyment of other human rights. Moreover, water quality and availability have to be ensured in a sustainable manner by avoiding water contamination and overabstraction of water resources. Adaptability may be key to ensure that policies, legislation and implementation withstand the impacts of climate change and changing water availability.

Answer:

As already has been mentioned, the Rhine Action Programme had four phases. Sustainability is central to the last stage of the programme. The continuation of the programme through the making of two new agreements made that the protection of the Rhine, as well as the other objectives of the programme, was guaranteed.

The first agreement is the Convention on the Protection of the Rhine, which was signed on 12/04/1999 by representatives of France, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Switzerland and by the European

Community in Berne. Main objectives of this agreement were to increase multilateral cooperation on sustainable development of the Rhine ecosystem and the sustainability of the productions of drinking water from the waters of the Rhine.

In the year 2000, the successful results of the RAP Programme needed a follow-up programme for the next 20 year. In January 2001, the ministers of the Rhine countries adopted the “Rhine 2020, the Programme on the

Sustainable Development of the Rhine”. It determines the general objectives of Rhine protection policy and the measures required for their implementation for the next 20 years. The Balance on the Implementation of the

Measures of the Programme "Rhine 2020" shows first successes but also that further efforts are required, like for instance the improvement of the biodiversity of river banks.

Final remarks, challenges, lessons learnt

The Action Rhine Programme has shown that it is possible to improve the water quality of the strongly polluted river water of the Rhine on such a manner that people again can drink the water of the Rhine.

Important for the succeeding of the programme was the international cooperation between the Rhine countries and the willingness from the chemical industry to take an active role in the process. Although the Rhine Action

Programme has made enormous progression in the improvement of the water quality of the Rhine and in declining the risk of new accidents that could harm the human right situation, alertness is still needed because accidents still may occur. This means that an important step in the direction of totally safe drinking water produced of Rhine water has been taken. But to date, there are still a few substances of which too great amounts flow down the Rhine and into the North Sea. Especially substances from agriculture such as nitrogen remain to be a problem. Very recently, pharmaceutics and certain substances with hormonal effects in the Rhine water have become focus of attention. (Thomas P. Knepper, The Rhine, The handbook of the environmental Chemistr,

2006, page 71)

13

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation

Good Practices Questionnaire - iewater@ohchr.org

These steps are needed but they are relative small steps compared to the enormous progression there is made in the last two decennia, under the Rhine action Programme to improve the water quality of the Rhine.

Was it still dangerous to drink the water of the river in the mid-eighties, to dated, 20 million people became there drinking water from the Rhine without any bias. From an open sewer the Rhine became a spring of live.

Submissions

In order to enable the Independent Expert to consider submissions for discussion in the stakeholder consultations foreseen in 2010 and 2011, all stakeholders are encouraged to submit the answers to the questionnaire at their earliest convenience and no later than 30 th

of

June 2010.

Questionnaires can be transmitted electronically to iewater@ohchr.org (encouraged) or be addressed to

Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

ESCR Section

Human Rights Council and Special Procedures Division

OHCHR

Palais des Nations

CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland

Fax: +41 22 917 90 06

Please include in your submissions the name of the organization submitting the practice, as well as contact details in case follow up information is sought.

Your contact details

Name: Dr. Claudia Mahler

Organisation: German Institute for Human Rights, Zimmerstraße 26-27, 10969 Berlin,

Germany

Email: mahler@institut-fuer-menschenrechte.de

Telephone: +49-30-259359-125

Webpage: +49-30-259359-59

The Independent Expert would like to thank you for your efforts!

For more information on the mandate of the Independent Expert, please visit http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/water/Iexpert/index.htm

14