Submission by the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children

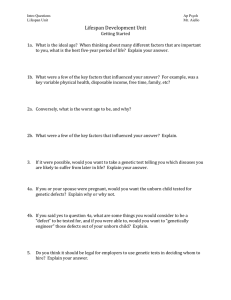

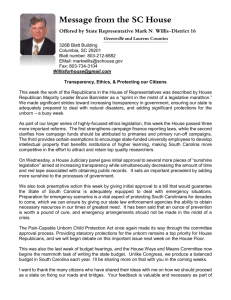

advertisement