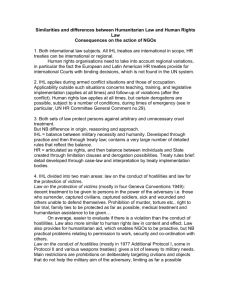

Written contribution to the general discussion on the

advertisement