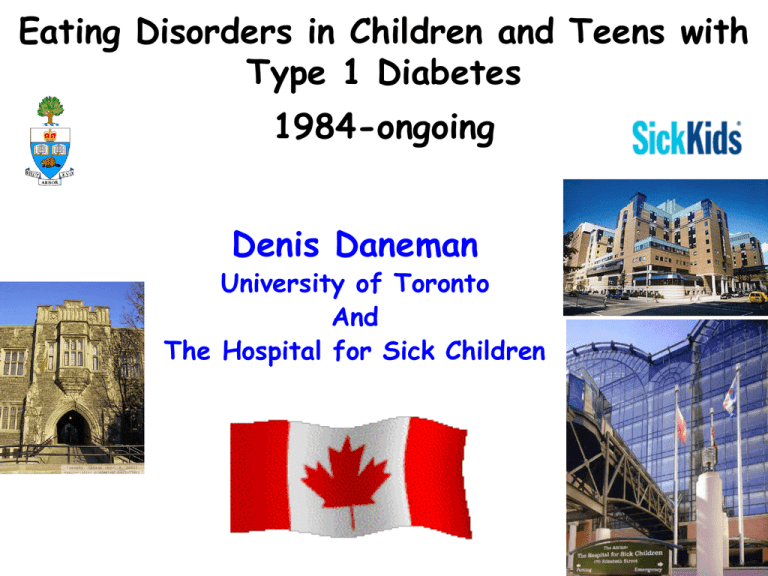

Eating Disorders in Children and Teens with Type 1 Diabetes 1984-ongoing Denis Daneman

advertisement

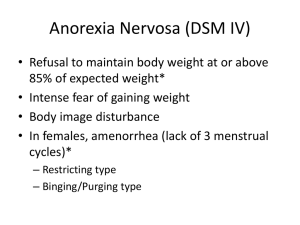

Eating Disorders in Children and Teens with Type 1 Diabetes 1984-ongoing Denis Daneman University of Toronto And The Hospital for Sick Children ED Classification • Clinical/full-blown: DSM-lV: – Anorexia nervosa – Bulimia nervosa – Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) • Subthreshold (not subclinical) – Disturbed Eating Behavior that does not meet criteria for full-blown ED, but with clinical consequences (e.g. A1c, complications) Working Model: Rodin & Daneman 1992 Diabetes-specific vulnerabilities: Individual, family, and societal factors Insulin-related weight gain Nutritional counseling Poor self-esteem Eating Disorders: Core Features: Body dissatisfaction Drive for thinness Dietary restraint Disordered eating attitudes and behavior: Diabetes-specific outcomes: Poor metabolic control: high HbA1c Microvascular complications, e.g., retinopathy Insulin omission Binge eating Dieting Predictions arising from our model: 1. Prevalence 2. Natural history 3. Associated with • • • • poorer control specific behavior, especially insulin omission early complications specific family issues 4. Difficult to treat Jones et al, BMJ 2000: DSM-IV diagnosable ED • DM: 356 – DSM-IV: 36 (10%) • AN 0 (0) • BN 5 (1.4) • NOS 31 (8.7) • Controls: 1098 (3:1) 49 (4%) <.001 0 (0) NS 5 (0.5) NS 44 (4.0) <.001 OR = 2.4 (1.5-3.7) Jones et al, 2000: Subthreshold Disorders: • DM: 356 – 49 (14%) • Controls: 1098 84 (8%) <.001 OR = 1.9 (1.3-2.8) DSM-IV + ST 85 (24%) 134 (12%) OR = 2 Obstacles identified during initial assessment Intrapersonal Barriers Number (%) Mental health issue in teen (total) Weight and shape concern Low Mood Anxiety Substance abuse Oppositional behavior 25 (81%) 18 (58%) 10 (32%) 6 (19%) 3 (10%) 2 (6%) Fear of Hypoglycemia 6 (19%) Learning and attention problems 4 (13%) Significant knowledge deficit 0 Interpersonal Barriers Single Parent Family 13 (42%) Inadequate or ineffective parental support 29 (94%) Family systems difficulties 26 (84%) Mental health issues in parent(s) 10 (32%) Financial stress 13 (42%) *multiple obstacles were identified in the majority of these subjects HbA1c (%) HbA1c by Disordered Eating Status at Baseline and Follow-up. 11.5 11 10.5 10 9.5 9 8.5 8 7.5 7 6.5 6 Baseline Follow-up *Highly disordered** Moderately disordered** Non-disordered *HbA1c for the highly disordered group was significantly higher than the moderately and non-disordered groups at baseline, p<.001; **HbA1c for the highly and moderately disordered groups was significantly higher than the non-disordered group at follow-up, p<.005 (Rydall et al., 1997). Common behaviors in girls with type 1 diabetes. 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Baseline Follow-up Binge *Dieting **Insulin ***Self- Laxative eating omission induced use vomiting McNemar’s test for change in prevalence, baseline to follow-up: *p=0.01; **p=0.003; ***p=.06 (Rydall et al., 1997). Prevalence of Insulin Omission (%) Age and Prevalence of Insulin Omission for Weight Control. 40 30 Insulin Series1 Omission 20 10 0 1 9-13 years 1Colton 2 3 12-18 years 16-22 years et al., 2000 (n=90): 1% prevalence of insulin omission in pre-teen girls; et al., 1997 (n=91): 14% in adolescent girls (baseline assessment); 3 Rydall et al., 1997 (n=91): 34% in young adult women (four-year follow-up of baseline sample). 2 Rydall Evolution of ED in teen girls with T1D • In progress, study of natural history of ED in girls with T1D; – Baseline: 101 9-13.9 yo with T1D & 303 controls – Follow-up of DM cohort for 5-8 years • Demographics at Baseline: – Mean age – Mean A1c – Mean duration of T1D 11.8 years 8.2% 4.7 years DISTURBED EATING BEHAVIOUR (last month) 20 16 * 12 % * 8 4 0 Diet Intense Exercise Binge Insulin 1 or more 2 or more Omission T1D School EATING DISORDERS: T1D VS. SCHOOL GIRLS 10 8 % sample 6 p = .001 ED-NOS SUBTHRESHOLD 4 2 0 T1D School No sign differences in: •Age •A1c •Duration of T1D Those with ED BMI > those without FIVE-YEAR FOLLOW-UP • 13.3% of participants (13/98) met criteria for an ED • 3 girls had bulimia nervosa • 3 had ED-NOS • 7 had a subthreshold ED • 44.9% of participants were classified as overweight or obese FIVE-YEAR FOLLOW-UP • A1c not higher in girls with DEB –(8.7% vs. 8.4%; p = 0.11) • Trend for higher A1c in those with an ED –(9.1% vs. 8.5%; p = 0.08) • BMI higher in those with DEB –(26.1 versus 23.5; p = 0.001) ED POINT PREVALENCE & CUMULATIVE PREVALENCE BY AGE 50 45 40 35 30 % 25 20 15 10 5 0 ED point prev ED cumulative 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Age FIVE-YEAR FOLLOW-UP • Higher BMI and DEB were strongly associated, which presents a management dilemma • Both dietary restraint and higher weight are risk factors for the development of ED and their negative health consequences PREDICTION OF THE ONSET OF DISTURBED EATING BEHAVIOUR IN ADOLESCENT GIRLS WITH TYPE 1 DIABETES LOGISTIC REGRESSION MODEL WITH BACKWARD STEPWISE REGRESSION Dietary Restraint Weight & Shape Concern Physical Appearance Self-Worth Depression X2 = 43.254, df = 5, p<.0001 McFadden’s R2 = 0.416 If the model is correct, then the prevalence of complications should be more common in ED: 100 80 60 Highly Disordered 40 20 0 Retinopathy* MicroAlbuminuria (Rydall et al., NEJM 1997). Moderately Disordered Non-Disordered Is family dysfunction more common in ED than nonED DM: To investigate if and how eating disturbances in girls with type 1 DM are associated with: 1. Mother’s weight and shape concerns 2. Mother-daughter relationships 3. Adolescent self-concept Method TEENS (N=88) MOTHERS (N=88) • Age = 14.9 yrs. (+ 2.2) • Age = 43.7 yrs (+ 5.5) • Weight = 58.9 kg (+12.7) • Weight = 69.3 (+13.7) • • BMI = 22.4 kg/m2 (+3.7) • Age of Diabetes Onset = 7.9 yrs (+ 4.0) • Illness Duration = 7.1yrs (+3.9) • HbA1c = 8.9 % (+ 1.6) BMI = 25.9 (+4.9) • Middle Class • Completed 1-2 years of college, university, or specialized training Perceived Relationships With Mothers Non 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Communic. Alienation Communic.Trust Trust Alienation Mildly • Multivariate Group effect [F(6, 160 ) = 3.97, p =.001] Highly Highly & Mildly Disturbed girls report more impaired relations with mothers on all dimensions compared to Non-Disturbed girls (p = .01) Figure 8: Observed Mother-Daughter Interaction Patterns. Non • MANCOVA illustrated a significant Group effect (p=.0005), with all three groups differing from each other on Mother Autonomy (p=.001), Adolescent Autonomy (p=.01) & Intimacy (p=.0005). • There was a significant Task effect (p=.0005), with more impairment in Adolescent Autonomy (p=.0005) and Intimacy (p=.001) during diabetes-related discussions. M ildly Highly 5 4.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 M other Autonomy Teen Autonomy Intimacy (Maharaj et al., in press) Mother’s Eating and Weight Loss Behaviors 4.8 4.3 3.8 3.3 2.8 2.3 1.8 1.3 0.8 0.3 -0.2 Sa tis fie Ex d erc ise Di et Bi ng e Satisfaction Diet Exercise Binge Non Mildly Highly • Multivariate Group effect [F (10, 138) = 2.12, p = .03] • Mothers of Highly & Mildly Disturbed girls are more weight dissatisfied (p = .01) and are more likely to exercise for weight control (p = .02), diet (p = .05), and binge eat (p = .02). Prevention and Treatment in DM and ED: • Prevention: not reported • Treatment: –CBT - Peveler and Fairburn 1989 –Fluoxetine - case report - 1990 –Psychoeducation - Olmsted 2000 Evidence-based conclusions: Model validation • Eating disorders are more common in adolescent and young adult females with diabetes (Level 1) • When present they are associated with – high frequency of insulin omission (Level 1) – worse metabolic control (Level 2) – earlier onset of complications (Level 1) – family dysfunction (Level 2) • They are (more) difficult to treat (Level 4) Approach to ED in DM • Awareness of the association • Ask the “right” questions • If suspect “fullblown” ED refer • If subthreshold - clinic-based intervention • Complication surveillance Asking the “right” questions “Red flags” Dealing with reluctance to disclose Their stories… Partnering with patients Regaining control Treatment options Red Flags Persistently high A1c Frequent DKA, illnesses Distress re: weight Widely fluctuating b.g.s Skipping meals “Binging”; feeling hungry all the time Skipping dosing/underdosing Initial response to high A1c: Raise the dose Labeled “insulin resistent” Problem: “insulin avoidant” Disclosure is very difficult Shame Feel like “failures” Failed: Their families Their providers Themselves Important to be nonjudgemental and supportive In their words…. A start…. Information can be helpful “Unfortunately something many young people struggle with…” Insulin omission drives hunger Losing control over eating behavior Information for parents Families are angry, blaming They feel like failures too Regaining control A step at a time Steps forward, steps back Treatment options: Partner with existing ED programs Requires collaboration Groups Conventional treatment Medication/Consult