2007 7 DPI WORLD ASSEMBLY IN KOREA

advertisement

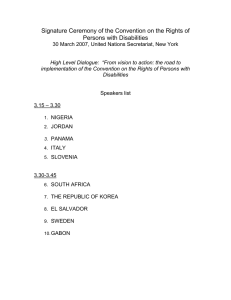

2007 7TH DPI WORLD ASSEMBLY IN KOREA KEYNOTE ADDRESS By MS KYUNG-WHA KANG, DEPUTY HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PARTNERSHIP OF THE UNITED NATIONS AND DISABLED PERSONS ORGANIZATIONS FOR DISABILITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS 6 SEPTEMBER 2007 1 I am delighted to participate in the 7th DPI World Assembly in Korea, to discuss the partnership between the United Nations and organizations representing persons with disabilities. As a Korean, I share the pride and sense of accomplishment with the disabilities groups of this country in having successfully prepared for this World Congress. This gathering is of great importance for the rights of persons with disabilities as well as for the UN’s work in the area of human rights. I wish to convey to you the best wishes of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, whom I represent here. I take great pride in having actively participated in the drafting of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. I rejoiced in the successful conclusion of that process in the fall of last year and the opening of the Convention for signing in March this year. And now with all of you, I await the entry into force of the Convention, and, along with my colleagues at the Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR), the work of assisting the committee that will monitor the implementation of the Convention. The Convention is the response of the international community to the long history of discrimination, exclusion, and dehumanization of persons with disabilities. It is the result of three years of intense negotiations involving civil society, governments, national human rights institutions and international organizations, with the support of the UN Secretariat. My task today is to share with you some thoughts on further nurturing the partnership between the UN and organizations representing persons with disabilities, which had been vital for the unprecedented speed and richness of debate with which the Convention was drafted and adopted. Allow me to start on a note of realism. Those of us who had been a part of the Ad Hoc Committee that drafted the Convention over a period of three years were witnesses to quite an extraordinary undertaking. Many of you who had been a part of the process may disagree, but by UN standards, the Ad Hoc Committee, was, in many ways, the UN at its best. That’s the good news, but it is also the bad news. As far as NGO participation in inter- governmental process at the UN is concerned, the Ad Hoc Committee was the high mark. Whether that experience can be replicated in other arenas, and in other areas of work is very much an open question. 2 From its beginning, the United Nations has always had a place for civil society input and NGO participation. In article 71, the UN Charter states that the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) may make suitable arrangements for consultation with non-government organizations which are concerned with matters within its competence. Over the six decades, ECOSOC has adopted rules to make those suitable arrangements and thus to enable NGOs to participate in its deliberation as well as those of its functional commissions. The arrangement has evolved to the current stage, where a Committee of representatives of 19 governments, elected by ECOSOC, reviews applications from NGOs for consultative status, and makes recommendations to ECOSOC regarding each application. The Committee can also recommend the withdrawal or suspension of the consultative status of an NGO. Today, there are almost 3,000, representing various countries, regions and areas of interest. NGO participation in the Security Council and the General Assembly, the other two principle intergovernmental bodies of the UN, has been granted through informal, temporary arrangements. In recent years the scope of NGO activities has expanded, and their aspirations to play a more active role at the UN has grown accordingly. Thus, in 2003, the former SecretaryGeneral tasked a panel of eminent persons, led by former President Cardoso of Brazil, to look at UN-civil society relations and propose measures to expand the way in which NGOs could participate in the work of the UN. The panel delivered many far-reaching recommendations, including that the task of reviewing NGO applications for consultative status be taken up by the General Assembly, instead of ECOSOC. There was much excitement when the panel report first came out in early 2004. Many government delegations in NY, including the Republic of Korea, which has always been a strong supporter of NGOs at the UN, were very receptive. To date, however, little has come of it, and the basic rules for NGO engagement in the UN inter-governmental process remain unchanged. The fact is that the UN at its core is an organization of Member States which are wary of creating greater space for non-governmental input and prefer to take a path of least resistance. It will take some time for the notion of “participatory democracy”, as practiced at the national level in many countries where civil society participation is extensively integrated into policy making and implementation, can take root at the UN. 3 This will happen only if Member States are willing to address what has been called “the UN democratic deficit whereby the General Assembly, which includes all member States, can adopt only decisions that are not legally binding, but the Security Council of just 15 Member States – 5 who are there permanently and 10 elected for two year terms – can make decisions that are binding on all others. This fundamental power asymmetry has triggered intense debate about UN reform, including on the need to expand the Security Council so that it may better reflect the world of today. Much has resulted from the reform efforts, including the establishment of the Human Rights Council, directly under the General Assembly, to replace the much criticized Commission on Human Rights, which had been a functional commission under ECOSOC. I say all of this, not to discourage but to point the way forward. While it may be unrealistic to expect early radical changes to the rules for NGO engagement in the UN, the trend is certainly toward greater involvement and influence. Furthermore, within the existing rules and framework, there are numerous ways in which NGOs can help the UN in its work. And beyond the inter-governmental machinery, there are many UN entities, including the Secretariat, that are ready to support and partner with NGOs. This is all the more so in the field of human rights, where the NGO activism and leadership is particularly rich and laudable. Let me now discuss some concrete ways in which DPOs can contribute to the work of the UN, in particular in the field of human rights. This would include: the Human Rights Council, the inter-governmental process; the treaty bodies, which are committees of experts that monitor implementation of human rights treaties by state parties; the system of special procedures, which are independent experts charged by the Council with thematic or countryspecific human rights mandates; and last but not least, OHCHR, which is a part of the UN Secretariat. At the level of inter-governmental decision-making, it is worth highlighting the potential for DPOs to strengthen their engagement with the Human Rights Council. The Human Rights Council is continuing the lengthy process of establishing its modes of operation. Consequently, there is an opportunity to ensure that this new body devotes adequate attention to disabilities. One important new feature of the Council is the introduction of a process known as the Universal Periodic Review, whereby the human rights record of every UN 4 Member State will be reviewed at regular intervals. The UPR could thus offer an opportunity to better monitor the performance of all States – not only those ratifying the new Convention – in the area of the rights of persons with disabilities. In turn, this could insert disability more solidly on the wider human rights agenda. I would also highlight opportunities for engagement with treaty monitoring bodies. When the new Convention comes into force, a new treaty body, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, will be established. The Committee will comprise independent experts, including experts with disabilities. There are several ways to engage with the Committee. For example, the new Convention stipulates that States must consult with and actively engage persons with disabilities through their representative organizations in relevant decision-making processes, including in the nomination of experts for the Committee. I encourage DPOs to identify qualified and capable experts taking into account the need for representation of experts from a range of different countries, legal systems and disabilities. Moreover, DPOs have a role to play in the review of specific countries. Each State that is party to the Convention will present a comprehensive report on measures taken to implement the Convention within two years of becoming a party. There is now a common practice for civil society organizations to prepare parallel country reports for the Committee – reports that provide a distinct and often more comprehensive review of the current human rights situation on the ground. The preparation of country reports can become a rallying point for civil society groups to compare lessons learned and to consider the way forward. Treaty bodies also engage directly with civil society groups during the country review offering an additional avenue for DPOs participation. in treaty body deliberations. DPOs should also work with the system of special procedures and with mandate holders. As independent experts in touch with human rights constituencies on the ground, these experts are often first responders to human rights needs.. Currently, there are 38 mandates reporting to the Human Rights Council, which is to embark on a review of each mandate at its 6th session that begins on September 10. The review may highlight protection gaps, calling for the creation of new mandates. While the attention in the coming months will be focused on the entry into force of the Convention and the establishment of the Committee to monitor its 5 implementation, it would be important for DPOs to closely follow the review discussions to see how existing mandates can fully incorporate the rights expressed in the Convention. Within the UN Secretariat, OHCHR and DESA (Department of Economic and Social Affairs) remain committed partners of DPOs. With the Convention adopted and ready to go into force, the action will move to Geneva where the monitoring Committee will work, with the assistance of OHCHR. To facilitate NGO engagement in the human rights machinery, OHCHR has newly established a Civil Society Unit, under my direct supervision. The Unit looks forward to working with DPOs. The challenge is establishing clear line of communications. To this end and with a view of creating an updated database, OHCHR civil society unit has recently sent out a questionnaire to DPOs. OHCHR is also ready to collaborate with DPOs on the ground through our field presence in some 40 countries: 11 country offices, 9 regional offices, human rights components in 17 UN integrated peace missions, and human rights advisors in 9 UN country teams. Where we don’t have field presence, we are urging the UN country teams –which are dispatched to nearly 140 countries – and the UN agencies affiliated with the teams to mainstream human rights into their activities. DPOs should encourage the UN country teams and agencies to integrate disability concerns into their programs. At this level of advocacy, it would be very useful for DPOs to join efforts with the national human rights institutions. An example of how this could be done is offered by election processes in which the UN is involved. Partnerships with the UN in the field during elections could highlight the need to ensure the accessibility of election processes for persons with disabilities so that all voters can enjoy their right to cast their ballot. Meanwhile, the UN Secretariat has its own work to do in terms of accessibility for DPOs. The General Assembly, when adopting the new Convention, requested the Secretariat to implement standards and guidelines for the accessibility of UN facilities and services progressively. The Secretariat, led by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, has begun implementing this request, focusing on three main areas: information, including information technology; human resources, including recruitment and training processes and the management of disability among staff; and physical facilities, including access to premises for staff, delegates, and/or visitors with disabilities. OHCHR has started undertaking an accessibility audit of its premises and facilities, including its website, 6 documentation, meeting facilities and buildings. I know that the UN, through these efforts, will become a more welcoming place for staff, experts and members of civil society with disabilities – but this will take time. Attitudes have to change, working methods reformed and budgets adjusted to ensure accessibility policies are implemented and sustained. Other challenges also exist. There is the question of resources – a factor relevant to both the UN and civil society. Ensuring comprehensive participation of civil society is a priority, but there are other priorities, deadlines and challenges that have to be met and limited resources might sometimes place constraints on partnership. An additional challenge is the increasing diversification of areas of engagement. While the drafting processes of the Convention provided one forum – the Ad Hoc Committee – and one focus – the new instrument– DPOs will increasingly be faced with a range of fora and organizations to engage with – the Human Rights Council, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and so on. Priorities will have to be set and resources allocated in order to optimize partnership. Some of these challenges will be easier to overcome than others. The breathing space we have now prior to the Convention’s entry into force provides us with a moment to reflect on how we can strengthen our partnership. Let me conclude by encouraging you to keep up the fight and reiterate the support of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN as we move forward to the exciting period of implementing the Convention. It is through the realization of its objectives that the world’s 650 million persons with disabilities will begin to enjoy the same rights and opportunities as everyone else. Thank you for your kind attention. 7