STATEMENT BY THE UNITED NATIONS EXPERT ON WATER AND SANITATION

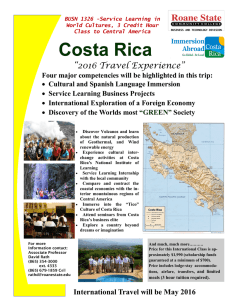

advertisement

STATEMENT BY THE UNITED NATIONS EXPERT ON WATER AND SANITATION (VISIT TO COSTA RICA, 19-27 MARCH 2009) 27 March 2009 From 19 to 27 March 2009, I conducted a mission to Costa Rica. The aim of my visit was to assess the way in which Costa Rica is implementing its human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation. This is my first country mission since I began serving as Independent Expert in November 2008. Let me begin by expressing my gratitude to the Costa Rican Government for inviting me to visit the country. This willingness to co-operate with the international community, witnessed by the standing invitation made by the Government to all special procedure mandate holders of the Human Rights Council, is admirable, and I wish to take this opportunity to thank the Government for the openness shown before and throughout the mission. I would also like to express my gratitude to UNDP for the support they have given me in the organisation of my visit. During the course of the mission, I met with a wide variety of actors, including representatives of various Ministries, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of the Environment, Energy and Telecommunications (MINAET) and the Ministry of Health (MINSALUD); members of the Asamblea Legislativa, representatives of municipalities, members of the judiciary, the Defensoría de los habitantes (Ombudsman), civil society organisations, United Nations agencies and bodies, the academia and the private sector. During my 9 days in the country, I travelled to several locations in the provinces of Guanacaste, Puntarenas, Limón and Cartago, where I visited schools, national parks, and a police station to look into issues related to my mandate. In these locations I had the opportunity to meet with different stakeholders. I welcome the significant progress made by the Government of Costa Rica in expanding access to safe drinking water and sanitation. At 82.2 per cent, Costa Rica has one of the highest rates of population with access to safe drinking water in the Latin American and Caribbean region. Costa Rica also made important progress in the field of sanitation, with an average 98 per cent of the urban and rural population having access to a source of improved sanitation. I also welcome the Government’s more integrated vision of all problems and connections between sanitation, water quality and security, environmental protection and health. During the years, Costa Rica has developed a comprehensive legal framework for the protection of access to safe drinking water and sanitation. In particular, I note with appreciation that the national policy in the field of water management recognises that access to safe drinking water constitutes an inalienable human right, and that use of water for personal consumption is prioritised over any other use. Nevertheless, I note that the Water Law (Ley de Aguas), which dates from the 1940s, no longer corresponds to the social and economic situation of the country, and requires revision and updating. There is wide awareness in the country on the urgent need for a new Water Law. Notwithstanding the positive developments related to water and sanitation in Costa Rica, there are some identifiable challenges which need to be addressed. Analysing the institutional framework of the water sector in the country, responsibilities with regard to water and sanitation are dispersed among a wide number of authorities, which results in overlaps and lack of clarity on matters related to water and sanitation. This framework also makes it difficult to identify the roles and responsibilities of the various institutions working in the water sector. Several institutions, with responsibility to monitor and enforce the implementation of the legal framework on water and sanitation, including the Environmental Administrative Tribunal do not have sufficient human and financial resources for carrying out their mandates. This is particularly true with regard to activities aimed at ensuring implementation of legislation to prevent water contamination and illegal drilling of wells, among others. In fact, different actors with whom I met identified this as one of the biggest challenges faced by Costa Rica in the domain of safe drinking water and sanitation. Although the overall percentage of the population with access to safe drinking water is very high compared to the rest of the region, there are still significant disparities between the rural and urban areas. Whereas access to safe drinking water in urban areas is over 95%, in rural areas, it is only around 60%. Furthermore, persons belonging to vulnerable and marginalised groups, including indigenous people, Afro-descendants, migrant workers and people living in poverty, often lack access to safe drinking water and sanitation – as UN human rights treaty bodies have mentioned on several occasions. Disparities and inequalities in water prices, depending on the authorities responsible for the management and provision of water – the Costa Rican Institute for Aqueducts and Sewers (Instituto Costarricense de Acueductos y Alcantarillados – AyA), municipalities or the Administrative Associations for Aqueducts and Sewers (known by their Spanish acronym ASADAS) - are also a matter of concern. I also note the fact that there is no national policy on water that takes into account the special situation of people living in poverty. Pollution of waters with chemicals and waste waters, namely in coastal areas and zones with intense farming, is a concern, which is shared by different actors in the country. I am also worried about the fact that some people that I met with in Sardinal informed me about the alleged lack of access to safe drinking water and also about the populations’ general fear that the water scarcity in the region will increase. Moreover, I express my concern that only 3.5% of waste water is treated. In this context, I welcome the public recognition by the Government of the problems the country is still facing in relation to sanitation, as well as the very significant financial investment that it is undertaking to solve the situation. I also note with appreciation the fact that the Government announced it intention to increase the rate of waste water treatment from 3.5% in 2008 to 28% in 2015. I would like to take this occasion to make some – very preliminary – recommendations. My intention is to make more articulated recommendations to the different actors I met with in my final report, which will be ready in the coming months. My report will be publicly discussed at the United Nations Human Rights Council in September. Preliminary recommendations: 1. Improve, as a matter of priority, the treatment and disposal of waste water throughout the country, including in rural and coastal areas, with the aim of reducing the pollution of water sources. 2. Move as expeditiously as possible towards the adoption of the new Water Law (Ley de recursos hídrico). The new law should expressly recognise water as a human right, in accordance with the various decisions adopted by the Constitutional Court (Sala Constitucional) on this issue and the national policy on water management. In drafting such a law, General Comment No. 15 on “The Right to Water” of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights should be taken into account. Finally, civil society organisations working on human rights, environmental and water-related issues should be involved in the design, as well as in the future implementation, of the law. 3. Adopt all necessary measures, including affirmative measures, to eliminate any form of indirect discrimination against persons belonging to marginalised and vulnerable groups, including indigenous peoples, Afro-descendants, migrants and persons living in poverty. Take the necessary steps to remove the economic, social and geographical barriers that prevent such communities from accessing safe drinking water and improved sanitation. 4. Clarify the functions and responsibilities of the various institutions working in the water sector with a view to improving efficiency in water management and avoiding possible conflicts and overlaps. Consider streamlining, and possibly simplifying, the organisation of the water sector. 5. Improve the capacity of bodies responsible for monitoring and ensuring implementation of legislation on water and sanitation by increasing their human and financial resources. Ensure proper follow up to the decisions taken by these bodies. 6. Provide information to relevant stakeholders, especially civil society organisations and members of affected communities, and involve them in decision-making processes related to the use and management of water sources. 7. Carry out a comprehensive study on the availability and quality of superficial and subterranean waters (balance hídrico), with a view to ascertaining the availability of water for different uses.