A Advance Unedited Version Human Rights Council

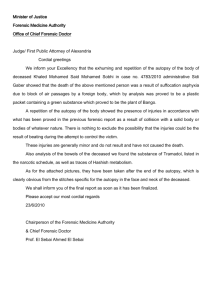

advertisement