CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child

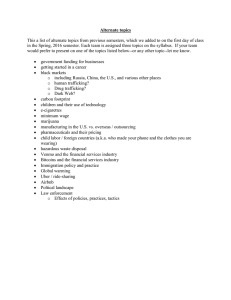

advertisement