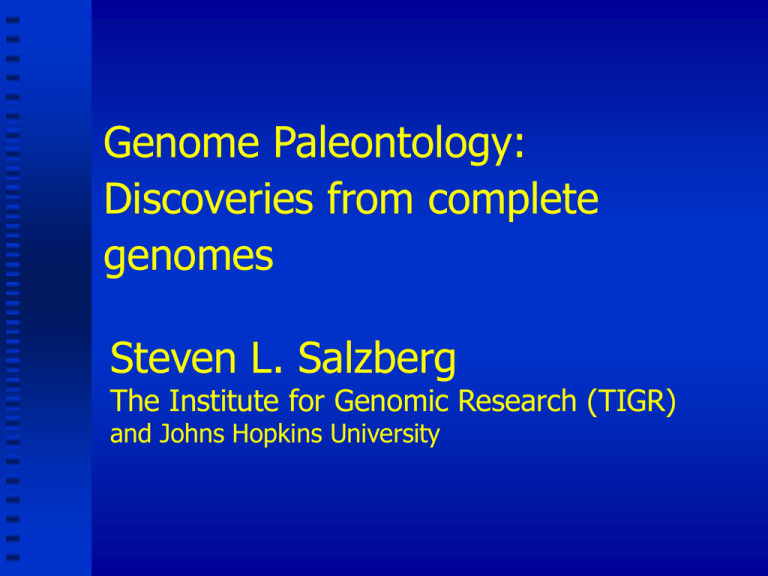

Genome Paleontology: Discoveries from complete genomes Steven L. Salzberg

advertisement

Genome Paleontology: Discoveries from complete genomes Steven L. Salzberg The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) and Johns Hopkins University What is genome paleontology? Compare genomes to uncover: • history of species • genome transformations • recent mutations such as SNPs • evolution © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 2 Outline (time permitting) An algorithm for rapid large-scale alignment A.L. Delcher, S. Kasif, R.D. Fleischmann, J. Peterson, O. White, and S.L. Salzberg. Alignment of whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 27:11 (1999), 2369-76. MUMmer 2: Delcher et al., NAR, 2002. Alignments and analyses of bacterial genomes J.A. Eisen, J.F. Heidelberg, O. White, and S.L. Salzberg. Evidence for symmetric chromosomal inversions around the replication origin in bacteria. Genome Biology 1:6 (2000), 1-9. Large-scale genome duplications: plant and human • The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408 (2000), 796815. • J.C. Venter et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science 291 (2001), 1304-1351. ● Lateral gene transfer between humans and bacteria • S.L. Salzberg, O. White, J. Peterson, and J.A. Eisen. Microbial genes in the human genome: lateral transfer or gene loss? Science 292 (2001), 1903–1906. Organism Arabidopsis thaliana Archaeoglobus fulgidus Bacillus anthracis Ames Bacillus anthracis Florida Borrelia burgdorferi Brucella suis Caulobacter crescentus Chlamydia pneumoniae Chlamydia muridarum Chlamydophila caviae Chlorobium tepidum Coxiella burnetii RSA 493 Deinococcus radiodurans Enterococcus faecalis Haemophilus influenzae Helicobacter pylori Methanococcus jannaschii Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mycoplasma genitalium Neisseria meningitidis Oryza sativa (rice) chr 10 Plasmodium falciparum Plasmodium yoelii Porphyromonas gingivalis Pseudomonas putida Shewanella oneidensis Streptococcus agalactiae Streptococcus pneumoniae Sulfolobus islandicus virus Thermotoga maritima Treponema pallidum Vibrio cholerae Reference Lin et al., Nature 402: 761-8 (2000) Klenk et al., Nature 390:364-370 (1997) Read et al., Nature 423: 81-86 (2003) Read et al., Science 296, 2028-33 (2002) Fraser et al., Nature 390: 580-586 (1997) Paulsen et al., PNAS 99 (2002) Nierman et al., PNAS 98 (2001) Read et al., Nucl. Acids Res. 28, (2000) Read et al., Nucl. Acids Res. 28, (2000) Read et al., Nucl. Acids Res. 31, (2003) Eisen et al., PNAS 99: 9509-9514 (2002) Seshadri et al., PNAS 100: 5455-60 (2003) White et al., Science 286 (1999) Paulsen et al., Science 299: 2071-2074 (2003) Fleischmann et al., Science 269, (1995) Tomb et al., Nature 388:539-547 (1997) Bult et al., Science 273:1058-1073 (1996) Fleischmann et al., J. Bact.184, (2002) Fraser et al., Science 270:397-403 (1995) Tettelin et al., Science 287 (2000) Wing et al., Science 300: 1566-1569 (2003) Gardner et al., Nature 419:531-534 (2002) Carlton et al., Nature 419:512-519(2002) Nelson et al., J. Bact., in revision. Nelson et al., Envir. Microbiol. (2002) Heidelberg et al., Nat. Biotech. 20 (2002) Tettelin et al., PNAS. 99 (2002) Tettelin et al., Science 293 (2001) Arnold et al., Virology 15:252-66 (2000) Nelson et al., Nature 399: 323-329 (1999) Fraser et al., Science 281: 375-388 (1998) Heidelberg et al., Nature 406, (2000) Genomes completed and published by TIGR and our collaborators, 1995-present 4 Genomes in progress or recently completed Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans Bacillus anthracis Kruger B Burkholderia mallei Clostridium perfringens ATCC13124 Dehalococcoides ethenogenes Desulfovibrio vulgaris Ehrlichia chaffeensis Ehrlichia sennetsu Geobacter sulfurreducens Listeria monocytogenes Methylococcus capsulatus Mycobacterium avium 104 Mycobacterium smegmatis Pseudomonas syringae Staphylococcus aureus Staphylococcus epidermidis Treponema denticola Wolbachia sp. Anaplasma phagocytophila Bacillus cereus 10987 Bacteroides forsythes Brucella ovis Baumannia cicadellinicola Campylobacter jejuni Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans Colwellia sp. 34H Dichelobacter nodosus Fibrobacter succinogenes Prevotella intermedia Pseudomonas fluorescens Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 Streptococcus agalactiae A909 Streptococcus gordonii Streptococcus mitis Streptococcus pneumoniae 670 Acidobacterium capsulatum Bacillus anthracis A01055 Bacillus anthracis A0402 Bacillus anthracis Ames 0581 Burkholderia thailandensis Campylobacter coli RM2228 Campylobacter upsaliensis RM3195 Clostridium perfringens SM101 Epulopiscium fishelonii Hyphomonas neptunium Listeria monocytogenes F6854 Listeria monocytogenes H7858 Mycoplasma arthritidis Mycoplasma capricolum Myxococcus xanthus Prevotella ruminicola Pyrococcus furiosus Verrucomicrobium spinosum Actinomyces naeslundii Bacillus anthracis A0071 Bacillus anthracis Kruger B Erwinia chrysanthemi Gemmata obscuriglobus Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ruminococcus albus Streptococcus sobrinus Aspergillus fumigatus Brugia malayi Coccidioides immitis Cryptococcus neoformans Entamoeba histolytica Oryza sativa Chromosome 3 & 10 Plasmodium vivax Schistosoma mansoni Solanum spp. Tetrahymena thermophila Toxoplasma gondii Theileria parva Trichomonas vaginalis Trypanosoma brucei Trypanosoma cruzi 5 Genome-Scale Sequence Alignment • Efficiently compute alignments between entire genomes and chromosomes, for example: • Two strains of B. anthracis, each 5.1 Mb (<30 CPU seconds) • Two chromosomes of A. thaliana, each 20-30 Mb (< 5 minutes) • Two chromosomes of human, 100+ Mb each (< 30 minutes) © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 6 MUMmer alignments MUMs: Maximal Unique Matches Algorithm finds ALL matches String them together and align gaps Suffix trees Very fast alignment of long DNA sequences Linear time and space requirements Software at: http://www.tigr.org/software/mummer/ TIGR © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 7 Suffix Trees A trie A tree with edges labelled by strings Each leaf represents a sequence—the labels on the path to it from the root The suffix tree for sequences A and B : Contains |A | + |B | leaf nodes. Can be constructed in O (|A | + |B |) time! Holds all suffixes of a set of sequences © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 8 Maximal Unique Matches (MUMs) Sequences in genomes A and B that: Occur exactly once in A and in B Are not contained in any larger matching sequence A: B: © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg Occurs only here Mismatch at both ends 9 MUMmer 2 streaming algorithm Streaming String ...atgtcc... atgtgtgtc$ $ c$ 1 t gt 9 10 i+1 c$ gt c$ 7 8 c$ Suffix Tree for String atgtgtgtc$ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 gt 5 gtc$ 3 i gt c$ 6 c$ 4 © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg gtc$ 2 10 MUMmer results: M. tuberculosis CDC1551 vs. H37Rv a MUM A A C 48 G 164 T 11 C 66 89 159 G 164 81 61 T 9 169 44 Helicobacter pylori strain 26695 vs. J99 © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 12 V. cholera vs. E. coli (forward) V. cholera vs. E. coli (reverse) V. cholera vs. E. coli (both strands) Duplication and Gene Loss? © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 16 V. cholera vs. itself © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 17 S. pyogenes vs. itself © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 18 Symmetric Inversions Model A3 A2 32 1 2 30 31 3 29 4 28 5 27 6 26 7 25 8 24 9 23 10 22 11 21 12 20 13 19 14 18 17 16 15 A1 30 31 A1 Inversion around terminus 32 1 2 30 31 3 29 4 28 5 27 6 26 7 25 8 24 9 23 10 22 11 21 12 20 13 14 19 15 16 17 18 A2 * * 1 3231 3 2 30 4 5 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 * A2 Inversion around origin 29 28 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 19 * A3 14 15 16 17 18 32 1 2 3 29 4 28 5 27 6 26 7 Common 25 8 Ancester of 9 24 23 10 A and B 22 11 21 12 20 13 19 14 18 17 16 15 B1 A1 A3 A2 32 1 2 30 31 3 29 4 28 5 27 6 26 7 25 8 24 9 23 10 22 11 21 12 20 13 19 14 18 17 16 15 B1 32 1 2 30 31 3 Inversion 29 4 28 5 around 27 6 26 7 25* terminus * 89 24 10 11 12 13 14 B2 15 16 17 18 Inversion around origin 23 22 21 20 19 1 3231 3 2 30 29 4 28 5 27 6 26 7 8 25 9 24 10 23 11 22 12 21 13 20 14 19 15 16 17 18 * * B3 B3 B2 B1 © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg B3 B2 B2 19 M. tuberculosis M. leprae vs M. tuberculosis M. leprae © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 20 The “X-files” paper © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 21 Arabidopsis genome paleontology Compare all chromosomes to each other.... Diorama by B.E. Dahlgren, © The Field Museum, Chicago © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 22 The hunt for genome-scale duplications S. cerevisiae? 16% duplicated (Seoighe & Wolfe, 1999) Maize? 10 chromosomes vs. 5 in some related grasses; segmental allotetraploid? (Gaut & Dobley, 1997) Drosophila melanogaster - no duplications Vertebrates: much speculation but little evidence (Skrabanek & Wolfe, 1998) Arabidopsis thaliana: yes! © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 23 chr.4 First discovery: large-scale duplication between chromosomes 2 and 4 (Lin et al., 1999) chr.2 chr.1 Tandem duplications chr.1 • Over 60% of the genome is covered by duplicated regions • Centromeres cover much of the rest • Strikingly, only about 1/3 of the genes in each block remain as duplicates No triplications! 19-24 large-scale duplications >60% of the genome duplicated If duplications occurred over time, triplications highly likely Duplications likely happened as one event (on evolutionary time scale) Conclusion: whole genome duplication © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 27 I III IV V I III IV V Warning: Salzberg’s speculation follows Start with 4 ancestral chromosomes © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 28 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I III IV V 29 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I III IV V 30 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I III IV V 31 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I III IV V 32 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I III IV V II 33 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I III IV V II 34 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 35 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 36 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 37 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 38 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 39 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 40 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 41 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 42 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 43 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 44 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 45 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 46 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 47 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 48 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg I IV V II 49 I III IV V © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg II 50 I © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg II III IV V 51 I © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg II III IV V 52 I II III IV V Warning: data quality control Until December 2000, Arabidopsis data in GenBank was all BAC-based Errors included: BACs on the wrong chromosome BACs entered twice with different IDs, different annotation (sequenced twice), slightly different sequence For duplications analysis, these errors would prove disastrous Many of these errors are still in GenBank © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg Old BACs are not automatically deleted 54 Human Genome analysis used Celera’s assembly and annotation 26,588 genes, ordered along each of 24 chromosomes MUMmer 2.0 used to align whole chromosomes Nothing found in DNA-level alignments Proteome alignments used instead Recently re-computed using latest human genome annotation (Ensembl) © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 55 Human whole-genome aligment Create 24 “mini-proteomes” by concatenating all proteins on each chromosome Use MUMmer to align each mini-proteome to the complete proteome (9,675,713 amino acids) Search for conserved clusters of proteins Confirmed analysis by looking at Blast hits of all vs. all © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 56 What we’re looking for Not looking for tandem duplications domain hits (very common, often give highly significant Blast hits) © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 57 Summary results 1077 duplicated blocks 10,310 “gene pairs” “pair” = 2 genes that match between two blocks 296 blocks with 3-4 gene pairs 781 blocks with 5 or more gene pairs 3522 distinct genes, many duplicated more than once Large block: 33 genes on chr 2 and chr 14 spans 63Mbp on chr 14, over 70% of chr 14’s length spread over 97 genes on chr 2 and 332 genes on 14 includes two of four known Hox clusters, an ancient duplication Large block: 64 genes on chr 18 and chr 20 previously undiscovered Shuffled data: 370 gene pairs (3.6% false positive rate) © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 58 © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 59 Duplications in Human Chromosome 2 © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 60 Human-mouse genome mapping Close evolutionary distance permits DNA-level alignments Protein similarity even greater than DNA MUMmer quickly aligns each mouse miniproteome to its human counterparts Blast finds most (not all) of the same matches (and is far slower) 77% (566/731) of Mouse16 genes are found in syntenic regions of human 2.5% (18/731) of Mouse16 genes are unique to mouse, not found in human © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 61 Mouse chr 16 maps to human chromosomes 3, 8, 12, 16, 21, and 22 © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 62 Have bacteria transferred their genes directly into the human genome? “Startling” discovery, Feb. 2001: 223 bacterial genes were laterally transferred into a vertebrate ancestor of humans (from the Nature human genome paper) © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 63 Horizontal (Lateral) Gene Transfer © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 64 Vertical Inheritance © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 65 Horizontal Gene Transfer ??? © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 66 Horizontal gene transfer in Arabidopsis thaliana chr 2 (Lin et al., Nature, 1999) 135 genes most closely related to cyanobacterial genes and thus likely were transferred from chloroplast to the nucleus Very recent transfer of > 250 kb section of mitochondrial genome Many additional older mitochondrial → nuclear gene transfers © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 67 Examples of Horizontal Transfers Antibiotic resistance genes on plasmids Pathogenicity islands Toxin resistance genes on plasmids Agrobacterium Ti plasmid Viruses and viroids Organelle to nucleus transfers © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 68 Mechanisms of Horizontal Transfer Plasmid exchange (prokaryotes) Mating/conjugation (prokaryotes) Viruses and viroids Organelle to nucleus exchange (eukaryotes) Scavenging from environment Passive absorption Fusion of cells © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 69 Nature human genome paper (2001): Evidence for transfer? Evidence: Genes match bacteria, but do not match non-vertebrate eukaryotes Or, genes really are in non-vertebrates, but have stronger match to bacteria Measured by BLAST E-value 113 of the 223 genes found in a broad spectrum of prokaryotic species © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 70 Alternative explanations Gene loss from a small sample of non-vertebrate eukaryotes Only 4 non-vertebrates used for analysis: fruit fly, nematode, yeast, and mustard weed (Arabidopsis) Large and diverse set of prokaryotes (over 30 organisms, including extremophiles) used as well Rapid divergence in non-vertebrate eukaryotes (evolutionary rate variation) Still-incomplete genomes (e.g., D. melanogaster) Erroneous annotation/gene finding Contamination © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 71 Re-analysis: number of “transfers” decreases with # of genomes analyzed 2000 1800 Number of genes in lateral transfer candidate set 1600 1400 Fruit fly C. elegans Arabidopsis Yeast Parasites 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 1 2 3 4 Number of protein sets removed © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 5 Other 72 Evolutionary Rate Variation © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 73 Trees Don’t Support Transfer © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 74 Birney et al., Nature special issue on human genome “The unfinished human genomic DNA may contain contamination, particularly from bacteria but also from other sources. .... If the predicted gene matches a bacterial gene more closely than any vertebrate gene then it will almost always be a contaminant.” © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 75 Were genes really transferred? NO Our re-analysis finds just 41 genes (Ensembl) or 46 (Celera) with best hits to bacteria – not 223 Great care is needed in order to make assertions of transfer from bacteria to humans All of these could be explained by alternative mechanisms More genomes will likely eliminate these remaining candidates At least 3 have already been found in Drosophila, 10 more in other species Implications would be significant; e.g., GMOs Even more care is needed when working with unfinished data Nature erratum to human genome paper, August 2001: “We agree.” © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 76 Acknowledgements MUMmer: Arthur Delcher, Jeremy Peterson, Rob Fleischmann, Owen White, Simon Kasif, Jonathan Allen, Sam Angiuoli, Adam Phillippy X alignments: Jonathan Eisen, Owen White, John Heidelberg Arabidopsis duplications: TIGR: Maria Ermolaeva, Owen White, Jonathan Eisen, Xiaoying Lin, Samir Kaul AGI collaborators: Klaus Meyer and all his MIPS colleagues, Mike Bevan Human duplications: Mark Yandell, Mark Adams, Mani Subramanian, Craig Venter (all formerly Celera), Ron Wides (BarIlan University), Art Delcher Lateral transfer: Jonathan Eisen, Owen White, Jeremy Peterson Funding support: National Institutes of Health (NHGRI, NLM) National Science Foundation (CISE, BIO) © 2003 Steven L. Salzberg 77