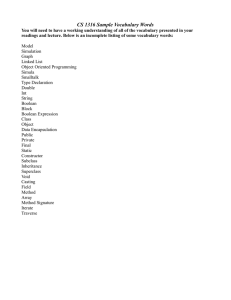

Where do objects come from? A brief history of object-oriented thought

advertisement

Where do objects come from? A brief history of object-oriented thought Dynabook to Personal Computer The Personal Computer* as we know it today was invented in pursuit of the Dynabook (*And object-oriented programming, too!) Start of the Story: Late 60's and Early 70's Windows are made of glass, mice are undesirable rodents Good programming = Structured programming Verb-oriented Structured Programming Define tasks to be performed Break tasks into smaller and smaller pieces Until you reach an implementable size Define the data structures to be manipulated Design how functions interact What's the input What's the output Group functions into components ("units" or "classes") Write the code Object-oriented programming First goal: Model the objects of the world Noun-oriented Focus on the domain of the program Phases Object-oriented analysis: Understand the domain Object-oriented design: Define an implementation Define an object-based model of it Design the solution Object-oriented programming: Build it How’d we get from there to here? How did we move from structured to object-oriented? Key ideas Master-drawings in Sketchpad Simulation “objects” in Simula Alan Kay and a desire to make software better More robust, more maintainable, more scalable Birth of Objects, 1 of 2 Ivan Sutherland's Sketchpad, 1963 Sketchpad First object-oriented drawing program Master and instance drawings Draw a house Make two instances Add a chimney to the master Poof! The instances grow a chimney Other interesting features 1/3 Mile Square Canvas Invention of “rubber band” lines Simple animations Birth of Objects, 2 of 2 Simula Simulation programming language from Norway, 1966 Define an activity which can be instantiated as Each process has it own data and behavior processes In real world, objects don't mess with each others' internals directly (Simulated) Multi-processing No Universal Scheduler in the Real World Alan Kay U. Utah PhD student in 1966 Read Sketchpad, Ported Simula Saw “objects” as the future of computer science His dissertation: Flex, an object-oriented personal computer A personal computer was a radical idea then Kay’s Insights “Computer” as collection of Networked Computers All software is simulating the real world Biology as model for objects Bacterium has 120M of info, 1/500th of a Cell, and we have 1013 of these in us What man-made things can scale like that? Stick a million dog houses together to get the Empire State Building? Internet does, but how can we make that the norm? Birth of Objects Objects as models of real world entities Objects as Cells Independent, indivisible, interacting -- in standard ways Scales well Complexity: Distributed responsibility Robustness: Independent Supporting growth: Same mechanism everywhere Reuse: Provide services, just like in real world Features of Objects Encapsulation: Can't mess with the innards Aggregation: Objects can be created overand-over and combined within other objects Inheritance: Objects can get structure (data) and behavior (methods) from another Alan points out that Inheritance is not the most important idea in objects. Empirically, more systems rely on aggregation than inheritance. "A Personal Computer for Children of All Ages" Flex, an object-oriented personal computer Flex Enabled by Moore's Law Logo, Sketchpad, and Simula Imagining personal computing in 1969 Learning representations and knowledge through programming them Keyboard and drawing tablet Computer as meta-medium The first medium to encompass other media Alan Kay’s Dynabook (1972) Alan Kay sees the Computer as Man’s first metamedium A medium that can represent any other media: Animation, graphics, sound, photography, etc. Programming is yet another medium The Dynabook is a (yet mythical) computer for creative metamedia exploration and reading Handheld, wireless network connection Writing (typing), drawing and painting, sound recording, music composition and synthesis One goal: End-user programming. But WHY? Prototype Dynabook (Xerox PARC Learning Research Group) A Dynabook is for Learning The Dynabook offers a new way to learn new kinds of things…and perhaps old things in better ways Dynamic systems (like evolution) Especially decentralized ones (Resnick, 1992) Knowledge representation (Papert, 1980) Programming (Kay & Goldberg, 1977) But need a system for creative expression In a time when “windows” were made of glass, and “mice” were undesirable rodents Smalltalk-72 For the Dynabook, WIMP was invented: overlapping Windows Icons Menus mouse Pointer How Smalltalk was Implemented Bytecode compiler Virtual machine to create the make-believe computer Machine language for a make-believe computer Invented years earlier by Burroughs Used in UCSD Pascal, Java, Python, etc. VM handles garbage collection, threading, etc. Four files needed for this implementation: VM (Very small: Typically less than 1M) Image file (in bytecode) Almost all of Smalltalk is written in Smalltalk Sources file (all sources always came along) Changes file (added sources by user) When you’re debugging how windows and addition works, you will crash the system 1981: Xerox releases Smalltalk-80 Smalltalk announced in August 1981 Byte magazine To prove portability, sends tapes to IBM, Sun, Apple, H-P, Tektronix Smalltalk research starts up at all these places Some Tektronix oscilloscopes have Smalltalk inside of them Spins off ParcPlace to market Smalltalk Adele Goldberg goes to run the new company Smalltalk-80 -> ObjectWorks -> VisualWorks ParcPlace -> ObjectShare + Neometron and then Cincom Other Smalltalks: Digitalk's Smalltalk/V and Quasar's SmalltalkAgents Back to the Future: Birth of Squeak 1995: Alan Kay, Dan Ingalls, Ted Kaehler are all at Apple Still want "A development environment in which to build educational software that could be used—and even programmed—by non-technical people and by children" Build on Open Source Software strengths Use the distributed power of Internet-based programmers Squeak Team Include John Maloney, Scott Wallace, and Kim Rose Maloney from Self: O-O at nearly C speeds Wallace: End-user programming, programming frameworks Rose: Education practice and study Wanted a new Smalltalk, but didn't have to build from scratch Apple had the original Smalltalk-80 still! "Build everything in Smalltalk" "We determined that implementation in C would be key to portability but none of us wanted to write in C." Make the Apple Smalltalk portable again Write a new VM all in Smalltalk Write a Smalltalk-to-C translator Spit out the new VM on the new Smalltalk Whole process: 16 weeks Squeak Even from the beginning, powerful implementation Released to the net, and ported to Windows and UNIX within five weeks Apple license allows commercial apps, but system fixes must be posted Squeak Team moves to Disney for several years. 16 voice music synthesis, all in Smalltalk In the end, it's about media. Squeak today (over 30 platforms) Media: 3-D graphics, MIDI, Flash, MPEG, sound recording Network: Web, POP/SMTP, zip compression/decompress Beyond Smalltalk-80: Exceptions, namespaces Breaking the Lines Six Basic Rules of Smalltalk Here’s the part that makes Smalltalk unusual 1. Everything is an object 2. All computation is triggered through message sends 3. Almost all of Smalltalk is <receiverObject> <message> 4. Messages trigger methods. 5. Every object is an instance of some class 6. All classes have a parent class, except for the root of the class hierarchy Parent is superclass, child is subclass Subclasses inherit behavior and structure from parent class. Sample Code | anArray anIndex aValue | "Declare three local variables" aValue := 2. "Set aValue to 2" anArray := Array new: 10. "anArray is an Array 10 elems" 1 to: 10 do: "Store 2*index at each array elem" [:index | anArray at: index put: (aValue * index)]. anIndex := 1. "Walk the array again, printing out the values" [anIndex <= anArray size] whileTrue: [Transcript show: 'Value at: ',(anIndex printString), ' is ', (anArray at: anIndex) printString ; cr. anIndex := anIndex + 1.] Sample code output Value at: 1 is 2 Value at: 2 is 4 Value at: 3 is 6 Value at: 4 is 8 Value at: 5 is 10 Value at: 6 is 12 Value at: 7 is 14 Value at: 8 is 16 Value at: 9 is 18 Value at: 10 is 20 Reviewing the Rules 1. Everything is an object aValue := 2 Set the value of variable aValue to point to a SmallInteger object whose value is 2. aValue := 'fred'. Could follow immediately and would be perfectly fine All variables can point to any object. 2. All computation is triggered through message sends Even things like 1 to: 10 do: is just a message send Reviewing the Rules 3. <recieverObject> <message> 1 to: 10 do: [] is a message 1 is the reciever to:do: is the message (Colons indicate an argument will follow) 10 and the block [] are the arguments 2 + 3 is a message 2 is the receiver + is the message 3 is an argument There are no predefined control structures in Smalltalk! Reviewing the Rules 4. Messages trigger methods to:do: whileTrue: and + are all messages that have corresponding methods There can be more than one method implementing the same message Which method gets executed is based on the class of the receiver, and the decision is made at runtime This is late-binding More than one kind of object can respond to the same message in its own way 3 + 5 and 3.1 + 5.2 are very different methods This is polymorphism Polymorphism lets you program in terms of goals not code Methods in class Object are accessible by every object by inheritance, like printString. Smalltalk isn’t the only language like this Self (from Sun) also has “pure” object-oriented semantics, like Smalltalk. Self is the fastest O-O language ever: 50% of the speed of C Incrementally optimizing compiler Used by Sun to create their Hotspot Java VM Alan Kay on Java and C++ “Java and C++ make you think that the new ideas are like the old ones. Java is the most distressing thing to hit computing since MS-DOS.” "I invented the term Object-Oriented and I can tell you I did not have C++ in mind." Java and C++ keep the objects, but lose the messages. Object.method() is a method invocation, but not a message send. The earliest Smalltalk’s were even allowed to change the message->method binding Smalltalk-72 literally passed the entire sentence after the receiver object to the receiver object. The receiver object could parse the message any way it wanted! Problems: Different syntax for different objects -> hard to read. Hard to make fast: Method lookup was slow. Java/C++ go far the other direction: No late-binding of message to method The key to objects are messages Just a gentle reminder that I took some pains at the last OOPSLA to try to remind everyone that Smalltalk is not only NOT its syntax or the class library, it is not even about classes. I'm sorry that I long ago coined the term "objects" for this topic because it gets many people to focus on the lesser idea. The big idea is "messaging" -- that is what the kernel of Smalltalk/Squeak is all about (and it's something that was never quite completed in our Xerox PARC phase). The Japanese have a small word -- ma -- for "that which is in between" -- perhaps the nearest English equivalent is "interstitial". The key in making great and growable systems is much more to design how its modules communicate rather than what their internal properties and behaviors should be. Think of the internet -- to live, it (a) has to allow many different kinds of ideas and realizations that are beyond any single standard and (b) to allow varying degrees of safe interoperability between these ideas. If you focus on just messaging -- and realize that a good metasystem can late bind the various 2nd level architectures used in objects -- then much of the language-, UI-, and OS based discussions on this thread are really quite moot. At PARC we changed Smalltalk constantly, treating it always as a work in progress -- when ST hit the larger world, it was pretty much taken as "something just to be learned", as though it were Pascal or Algol. Smalltalk-80 never really was mutated into the next better versions of OOP. Given the current low state of programming in general, I think this is a real mistake.