240 World War Looms

240

World War Looms

The World War I experience helped generate an anti-foreign and isolationist mood in

America. To many Americans, U.S. involvement in that "European war" had been a costly mistake and a tragic waste of human life. American idealism gave way to feelings of disillusionment and betrayal. Anti-foreign feelings increased when European nations, with the exception of Finland, failed to repay their war debts to America. Postwar bitterness made many Americans determined to avoid future European entanglements.

This isolationist mood surfaced in several ways. First and most important, the U.S. rejected the Treaty of Versailles and membership in its League of Nations. Later, in the

1930s, Congress strengthened U.S. isolation by passing strict neutrality laws.

Meanwhile, Congress restricted immigration from foreign nations with laws such as the

Quota Act of 1921 and the National Origins Act of 1924.

Despite America's isolationist mood during the 1920s and 1930s, events slowly pulled the U.S. toward an internationalist foreign policy. The first signs of this came in the

1920s with an international agreement at the Washington Conference to limit warship building. Another sign of interest in world affairs was the Kellogg-Briand Pact, in which

62 nations, including the U.S., signed a pledge outlawing war.

The U.S. also moved toward cooperation with Latin America. The Coolidge and

Hoover administrations were more willing to negotiate solutions to problems with Latin

American nations than were earlier administrations. President Franklin Roosevelt was also eager to improve U.S. Latin American relations. He promised the U.S. would adopt the policy of "a good neighbor." In what came to be known as the Good Neighbor

Policy, the U.S. pledged that it would end its past policy of interventionism in the internal affairs of Latin American nations.

Meanwhile, major developments abroad eventually caused America to become more involved in the affairs of the rest of the world. Postwar problems in Italy led to the rise in

1922 of the Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. Economic problems in Germany, as well as resentment over the Treaty of Versailles, led to the rise in 1933 of the Nazi dictator

Adolf Hitler. At first League of Nations, members such as Britain and France appeased the aggressive demands of these dictators. But the appeasement ended when Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939. Great Britain and France declared war on Germany -

- World War II began.

When war broke out in Europe, the U.S. reaffirmed its policy of neutrality. But this policy began to change when the Allies (Great Britain and France) seemed unable to stop the advance of the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan). In November 1939, the

U.S. abolished its arms embargo and allowed any country to buy weapons and military supplies from the U.S. This law helped the Allies more than the Axis. In March 1941, the U.S. gave the Allies even more help by lending them military equipment through the

lend-lease program. After Germany invaded the U.S.S.R. in June of 1941, this new member of the Allies also received lend-lease aid. In August of 1941, F.D.R. and Prime

Minister Winston Churchill of Great Britain drew up a statement of war aims called the

Atlantic Charter. In it, the U.S. and Great Britain (and later the U.S.S.R.) agreed to work for a world free from aggression. Meanwhile, the U.S. showed its disapproval of

Japanese aggression in Asia. The U.S. placed an embargo on the shipment of gasoline, scrap iron, and other commodities to Japan. The U.S. also began lend-lease aid to China, which was a victim of Japanese aggression.

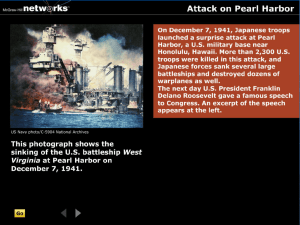

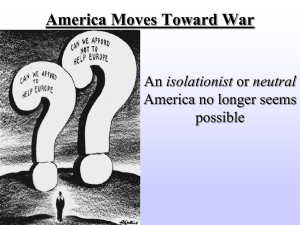

America's final step away from isolation towards full-fledged international participation came immediately after Japan's attack on the U.S. navy base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. With America's declaration of war on Japan, Japan's Axis allies

(Germany and Italy) declared war on the U.S. America became a full partner in the

Allied effort to defeat the Axis.