1930's Law and Justice | The Scottsboro Boys The Arrests.

advertisement

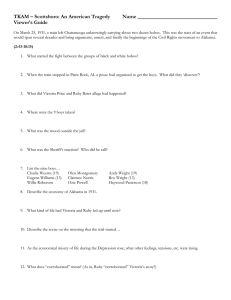

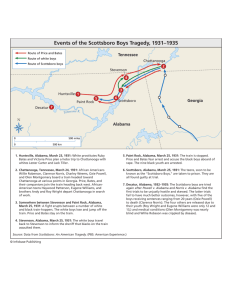

1930's Law and Justice | The Scottsboro Boys The Arrests. On 25 March 1931 a white youth, one of several who had picked a fight with a group of young black men aboard a Memphis-bound freight train, filed a complaint with local authorities in the town of Stevenson, Alabama. The police in neighboring Scottsboro were contacted and asked to stop the train, but it had already passed through. The Jackson County sheriff called a deputy near the next stop, Paint Rock, and had him deputize every available man to stop the train, arrest every black man on it, and return them to Scottsboro. Nine black youths, all transients and ranging in age from thirteen to twenty, were taken at gunpoint from the freight car in which they were found and arrested. Also discovered aboard were two white female mill workers, Victoria Price, age nineteen, and Ruby Bates, age seventeen. Fearful that they, too, would be arrested, they reported how they had been repeatedly raped by the black men in custody and forced to remain where they had been discovered. The nine, Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Haywood Patterson, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Charles Weems, Andrew Wright, Roy Wright, and Eugene Williams, were jailed, charged with rape, and held for trial in Scottsboro. The First Trial. The trials of the nine defendants began twelve days later in an atmosphere so charged with racial hatred that their safety could only be assured by the presence of a small force of deputies. Local editors had already concluded that the youths were guilty and should be treated severely, if only for the fact that they had dared to assault a white woman. The defendants were divided into four groups, based on their ages and the strength of the evidence against them. The first to be tried were Weems and Norris. Questions regarding the strength of the evidence against them arose almost immediately. The medical doctors who had examined the women testified that they had found little physical evidence of rape, that they had observed only minor bruises or lacerations on the body of Victoria Price and none on Ruby Bates, and that neither of the victims had displayed any sign of emotional trauma. There were inconsistencies as well in the accounts given by the women. Nonetheless, the all-white juries hearing the testimony were not disposed to render any verdict other than guilty. Eight of the nine were sentenced to be executed for their parts in the rape. Wright, age thirteen, was sentenced to life imprisonment. Picture at left: Attorney Samuel Leibowitz with the Scottsboro Boys in the Decatur, Alabama, jail. © UPI/Corbis-Bettmann. Public Reaction and Appeal. Shortly after the trials had been concluded, the cases of the young blacks came to the attention of the Communist Party and its affiliate, the International Labor Defense (ILD). With the assistance of such groups as the Anti-Imperialist League and the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, demonstrations were organized to publicize the plight of the young men and to raise funds for appeals of convictions. Taken by surprise by the strong public reaction to the unfairness of the proceedings in Alabama, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) attempted to assume control of the litigation but was rebuffed by the ILD. In the "Scottsboro Boys" the Communist Party had found a cause through which they hoped to demonstrate the extent to which the American judicial system had been corrupted. They had no intention of relinquishing control over the case. After the convictions of seven of the eight defendants who had received the death penalty had been upheld by the Alabama Supreme Court (which granted Williams a new trial), the United States Supreme Court, in the case of Powell v. Alabama, determined on 7 November 1932 that the defense of the Scottsboro Boys had been so seriously compromised by the errors and inadequacies of their lawyer that they had essentially been deprived of their constitutional right to counsel. Retrial. The new trials of the Scottsboro Boys, this time followed closely by the national media, began in March 1933 in nearby Decatur. Haywood Patterson was the first to be tried. Arrangements had originally been made for Clarence Darrow to defend the young men, but he had not been able to work with the ILD lawyers assigned to the case. Lead counsel for the nine would instead be the renowned criminal defense lawyer from New York Samuel Leibowitz. Conditions surrounding the new trials were virtually identical to those that had characterized the first. Leibowitz was maligned both for being Jewish and for his willingness to defend blacks. His defense strategy was an aggressive one. The testimony of Victoria Price was picked apart and her credibility destroyed. Ruby Bates took the stand and admitted that her and Price's accusations of rape had been fabricated. Other witnesses appeared to refute much of the state's evidence, but the jury remained unmoved. At the conclusion of the trial Patterson was found guilty and sentenced to death. Another Retrial. In June 1933 the judge who had presided over the retrial, James Edwin Horton, startled everyone by granting the defense's request for a new trial and transferring the case of Eugene Williams to juvenile court. A fair-minded jurist, he had not been impressed with the credibility of much of the testimony that had been offered against Patterson. Moreover, he was troubled by something he had not dared share with anyone at that time. During one of the trial's recesses, one of the medical doctors who had examined the victims had confronted each with his suspicions regarding their claims of rape, suspicions that the women did not deny. The doctor informed the judge that he could not testify to this exchange for fear that he would lose his practice as a result. As a result of his unpopular decision, Judge Horton was relieved of his assignment (and defeated for reelection to his judgeship in 1934), and another jurist was brought in to replace him. That yet another set of juries would again convict the seven defendants tried in Judge Horton's court in a series of trials in winter 1933 came as a surprise to no one. Another Appeal. In the fall of 1934, unknown to Leibowitz, two ILD attorneys offered Price $1,500 to repudiate her testimony. She informed the police and the attorneys were arrested with the bribe money still in their posession. The ILD was thoroughly discredited, and groups that originally had been held at arm's length became centrally involved in the defense effort. On 1 April 1935, in the case of Norris v. Alabama, the verdicts of the Scottsboro Boys were reversed on the grounds that Alabama had systematically excluded blacks from jury service, a deprivation of the defendant's right to a fair trial. The reaction in Alabama revealed the depth of feeling that had been aroused by the critical attention the case had focused on the state. Gov. Bibb Graves was moved to caution against any display of resistance to the ruling and instructed the state's courts to begin impaneling blacks as jurors. The newly formed Scottsboro Defense Committee, created in December 1935 and comprising members of the interested groups, assumed control of the case for the next round of trials, in 1936 and 1937, with Leibowitz still acting as chief counsel, though he ceded the questioning of witnesses to a southern attorney. And Yet Another Trial. Once again Patterson was to be the first to be tried, and once again he was convicted, though his sentence this time was seventy-five years in prison. Clarence Norris was tried next; he was convicted and sentenced to death. The trials of Andrew Wright and Charles Weems followed. The verdict for each was guilty, and they were sentenced to ninety-nine years and seventy-five years, respectively. Ozie Powell, who had assaulted a police officer on his return to prison after Patterson's most recent trial, was tried for assault only. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to twenty years. The prosecution declined to pursue charges against the other four defendents, and they were released. The End. Efforts to secure a pardon for those convicted met with stiff local opposition, though Governor Graves commuted Norris's death sentence to life imprisonment. Graves was invited to meet socially with President Roosevelt at Warm Springs, Georgia, though guessing that the president intended to ask him to consider a pardon, the governor declined to meet. In November 1943 the state released Weems, and in January 1947 Andrew Wright and Norris were paroled; though they left the state without permission and were sent back to prison. Charles Weems received his second parole in 1946, the year Ozie Powell was freed. Haywood Patterson escaped in 1948 and settled in Michigan, which refused to extradite him. In June 1950, the last of the Scottsboro Boys in prison, Andrew Wright, was paroled a second time. The case of the Scottsboro Boys remained a matter of general interest for more than the better part of the decade. No other event so clearly demonstrated the extent of racial injustice in the South. Prejudice of the most extreme kind possible had infected the proceedings from the beginning and had been responsible for its many questionable outcomes. The case remains an enduring symbol of "southern justice" that even the passage of time has failed to erase completely. Sources: Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969); Newsweek (13 April 1935): 19. ©2000-2011 Enotes.com Inc. All Rights Reserved