High School Advanced Placement Macroeconomics Course Outline

advertisement

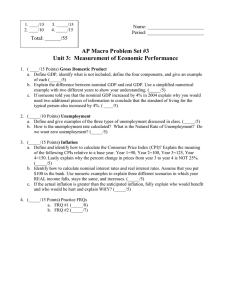

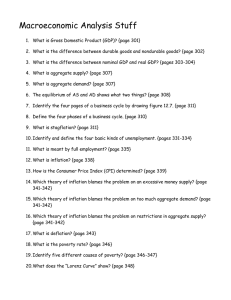

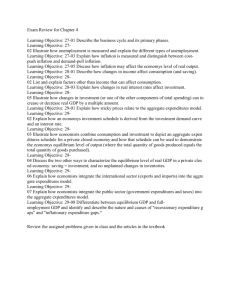

High School Advanced Placement Macroeconomics Course Outline Text: Economics, McConnell and Brue Workbooks: Macroeconomics: Student Activities, Morton and Goodman Numerous supplementary resources and materials Student Evaluation: Chapter 2: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Tests: Homework & In-class assignments: Term Paper: The Economizing Problem 60% 20% 20% (6 unit tests & 1 cumulative final) (Primarily from workbooks and textbook) (See Appendix I) I Basic Economic Concepts (Week 1) Full employment is the use of all available resources. Full production is the employment of resources so that they provide the maximum possible satisfaction of our material wants. Full production includes two kinds of efficiency: a) productive efficiency ( P = AC ) is the production of any particular mix of goods/services in the least costly way b) allocative efficiency ( P ( = MB ) = MC ) is the production of that particular mix of goods/services most wanted by society A production possibility curve/frontier represents some maximum combination of two products, which can be produced if full employment and full production are achieved. KEY GRAPH FIGURE 2 –1 PAGE 27 The opportunity cost of a specific good is the amount of other product, which must be foregone or sacrificed. The law of increasing opportunity costs states that the more of a product, which is, produced the greater is its opportunity cost. Economic growth is the ability of an economy to produce a larger total output as a result of increases in the supplies of resources, improvements in resource quality, and/or technological advance. FIGURE 2 – 4 AND 2 – 5 PAGES 31 – 32 A circular flow model (KEY GRAPH 2 – 6 PAGE 37) portrays an exchange between businesses and households in two markets: a) resource of factor market: households supply factors of production or resources (labor, capital, land, entrepreneurship) in exchange for resource payments (wages, interest, rend and profit or WIRP) b) product market: businesses supply finished goods/services in exchange for money from households Unit Activity: Stapler product activity Chapter 3: Understanding Individual Markets: Demand and Supply (Weeks 2-3) 1. Demand is a curve of schedule showing the various amounts of a product consumers are willing and able to purchase at a series of possible prices during a specific period 2. The law of demand states that as price falls, the quantity demanded rises and as price rises, the quantity demanded falls. There are three explanations for the law of demand: a) the law of diminishing marginal utility states that each buyer of a product will derive less satisfaction (or utility) from each successive units of a good consumed and thus will buy traditional units only of the price is reduced b) the income effect indicates that a lower price increases the purchasing power of a buyer’s money income, enabling the buyer to purchase more of the product c) the substitution effect indicates that at a lower price, buyers have the incentive to substitute the now cheaper good for similar goods which are now relatively more expensive. 3. Determinants of demand are non-price factors that will increase demand (shift right) or decrease demand (shift left) at all prices. Not that a change in demand is a shift of the entire demand curve due to one of the following demand determinants whereas a change in quantity demanded is movement along the curve due to a price change. The following are key determinants of demand: a) change in the price of a component – a decrease in the price of a complement (e.g. jelly) will result in an increase in demand for the good in question (e.g. peanut butter) b) change in the price of a substitute – an increase in the price of a substitute (e.g. bagel) will result in an increase in the demand for the good in question (e.g. donut) change in income – as income increases, a consumer’s ability to afford a normal product peanut butter increases and the demand for the product increases; however, if a good is an inferior good, consumers will decrease their demand if their income increases d) change in the number of buyers – an increase in population will result in more customers and an increase in demand e) change in consumer tastes – an item that is popular or desired will increase demand f) change in consumer expectations – consumer expectations of higher prices or higher income in the future will increase the demand for a good in the present c) 4. Supply is a schedule or curve showing the amounts of a product a producer is willing and able to produce and make available for sale at a series of possible prices during a specific period. 5. The law of supply states that as price rises, the corresponding quantity supplied rises and as price falls, the quantity supplied falls. To a supplier, higher prices represent higher revenue and thus are an increase incentive to produce and sell a product. 6. Determinants of supply are non-price factors that will increase supply (shift right) or decrease supply (shift left) at all prices. Note that a change in supply is a shift of the entire supply curve due to one of the following demand determinants whereas a change in quantity supplied is movement along the curve due to a price change. The following are key determinants of supply: a) resource prices – lower resource prices (labor, capital, land) decrease production costs, increase profits, and increase supply at each product price b) technology – improvements in technology decrease production costs, increase profits, and increase supply at each product price c) taxes and subsidies – whereas taxes will raise production costs, decrease profits, and decrease supply at each product price, subsidies will have the opposite effect (see a/b above) d) number of sellers – an increase in the number of suppliers will increase market supply 7. The market-clearing or equilibrium price occurs where the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. At any price above equilibrium, a surplus will occur, as the quantity supplied is greater than the quantity demanded and at any price below equilibrium, a shortage will occur as the quantity demanded is greater than the quantity supplied. KEY GRAPH FIGURE 3-5 PAGE 54. 8. Changes in supply and demand will result in a new equilibrium price and output. See table below and FIGURE 3-6 PAGE 55 Unit Activity: Market simulation II Measurement of Economic Performance Chapter 7: Measuring Domestic Output, National Income, and the Price Level (Week 4) 1. Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total market value of all final goods/services produced within a country in one year. GDP does NOT count in intermediate goods/services, secondhand goods, financial transactions (e.g. stocks, bonds), transfer payments (e.g. social security, unemployment insurance), profits/income earned by U.S. companies/individuals overseas. 2. GDP can be calculated in two ways: the amount spent to purchase this year’s output (i.e. expenditures approach) or the money income derived from producing this year’s total output (i.e. incomes approach). a) expenditures approach: consumption (C) + investment (I) + government (G) + net exports (Xn) b) income approach: wages (W) + interest (I) + rent (R) + profit (P) 3. Price indices are used to measure price changes in the economy; they are used to compare the prices of a given “market basket” of goods/services in one year with the prices of the same “market basket” in another year. A price index has a base year, and the price level in that year is given an index number of 100; the price level in all other years is expressed as a percentage of the price level in the base year: Price index number = current year prices x 100 base year prices 4. Nominal GDP is expressed in current dollars and is unadjusted for price changes whereas real GDP deflated or inflated for price-level changes. As a formula: Real GDP = nominal GDP_______ price index (in hundredths) Unit Activity: Calculate and track your market basket Chapter 8: Macroeconomic Instability: Unemployment and Inflation 1. (Week 5) Unemployment occurs when people who are willing and able to work cannot find jobs. The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force (including both those employed and those who are unemployed but actively seeking work): Unemployment Rate = unemployed x 100 labor force 2. There are four types of unemployment: a) frictional unemployment includes people who are temporarily between jobs. They may have quit one job to find another, or they could be trying to find the best opportunity after graduating from high school or college. b) Cyclical unemployment rises in a recession. For example, too little spending in the economy may cause it. c) Structural unemployment involves mismatches between job seekers and job openings. Unemployed people who lack skills or have a poor education are structurally unemployed. d) seasonal unemployment affects workers who have worked during the past year but are employed during other parts of the year due to seasonal conditions (e.g. weather-related jobs) 3. The full-employment unemployment rate is equal to total frictional and structural unemployment and occurs when cyclical unemployment is zero. It is currently estimated to be around 4 – 6%. 4. Potential GDP is the real output produced when the economy is fully employed. The GDP gap is the amount by which actual GDP falls short of potential GDP. According to Okun’s law for every 1 percentage point which the actual unemployment rate exceeds the natural rate, a GDP gap of about 2 percent occurs. FIGURE 8-5 PAGE 157 5. Inflation is a rising general level of prices whereas deflation is a falling general level of prices. 6. The inflation rate is calculated by the consumer price index (CPI) which measures the prices of a market basket of 300 consumer goods/services purchased by a typical urban consumer. 7. Nominal income includes wages, interest, rent, and profit received in current dollars whereas real income measures the amount of goods/services nominal income can buy. As an equation: % change in real income = % change in nominal income - % change in price level 8. While inflation reduces the purchasing power of the dollar (i.e. the amount of goods/services each dollar will buy), it does not necessarily decrease a person’s real income if nominal income rises with the price level. Unanticipated inflation will hurt the following groups: those on fixed incomes, savers, and lenders. 9. The nominal interest rate includes the real rate of interest (the % increase in purchasing power which the borrower pays the lender for the privilege of borrowing) and the expected rate of inflation. As a formula: Nominal interest rate = expected rate of inflation + real rate of interest If the nominal interest rate is 10% based upon an expected rate of inflation of 4%, the real rate of interest is 6%. If actual inflation is less than 4%, the lender gains and if the actual rate is greater than 4% the borrower gains purchasing power. 10. Three types of inflation include creeping, galloping, and hyperinflation. Unit Activity: Calculate and track your market basket (cont.)-Did we experience inflation? III National Income and Price Determination Chapter 9: Building the Aggregate Expenditures Model (Weeks 6-7) The amount of goods and services produced and therefore the level of employment depend directly on the level of total/aggregate expenditures. Aggregate expenditures includes C + I + G + Xn, although this chapter explores only C & I. 1. Disposable income is personal income – taxes. 2.Consumption is the largest component of aggregate expenditures. A consumption schedule shows the various amounts households would plan to consume at each of various levels of disposable income. If people consumed all of their disposable income, C = DI and this would be represented graphically as a 45 line. KEY GRAPH FIGURE 9-2 PAGE 176. 3. Savings equals disposable income less consumption or in symbols: S = DI – C. Graphically, savings is represented as the difference between the 45 line and consumption. KEY GRAPH FIGURE 9-2 PAGE 176. a) At low levels of disposable income, dissavings (consuming in excess disposable income) occurs as people draw upon accumulated wealth. b) Where C = DI, the consumption schedule intersects the 45 line and savings is zero (i.e. break-level of income). c) At higher levels of income, DI > C and S is positive. 4. A savings schedule shows the various amounts households would plan to save at each of various levels of disposable income. KEY GRAPH FIGURE 9-2 PAGE 176 5. Average propensity to consume is the percentage of any specific level of total income consumed. APC = consumption Income 6. Average propensity to save is the percentage of any specific level of total income saved. APS = Saving Income 7. will increase consumption and decrease savings at all levels of disposable income or APS = 1 – APC The marginal propensity to consume is the change in consumption due to a change in income. MPC = change in consumption Change in income 8. The marginal propensity to save is the change in savings due to a change in income. MPS = change in saving Change in income or MPS = 1 – MPC 9. The sum of MPC and MPS must equal 1. 10. There are non-income determinants of consumption and saving that will increase (shift up) or decrease (shift down) consumption and savings at all levels of disposable income. The major non income determinants are: a) Wealth: an increase in wealth will increase consumption and decrease savings at levels of disposable income. b) Expectations: consumer expectations of rising prices or shortages will increase consumption and decrease savings at all levels of disposable income. c) Household debt: an increase in household debt will increase consumption and decrease savings at all levels of disposable income d) Taxes: a decrease in taxes will increase both consumption and savings at all levels of disposable income. 11. Investment is the second component of aggregate expenditures. Businesses will invest in capital goods occur only if the marginal benefit from investment (i.e. the expected rate of return) exceeds or is equal to the marginal cost (i.e. the interest rate on the investment loan). KEY GRAPH FIGURE 9-5 PAGE 183 12. The investment schedule shows the amounts business firms collectively intend to invest at each possible level of GDP. We assume that investment is fixed, that is, independent of the level of current disposable income or real output. Thus, adding planned I to the consumption schedule (C=I) will shift the consumption schedule upward by the amount of the planned investment. FIGURE 10-1 PAGE 200 13. Although we assume investment is fixed, most likely at higher levels of GDP there is some induced investment as excess capacity disappears and firms have incentives to add to their capital stock. 14. The aggregate expenditures-domestic output model (aka. The incomes-expenditure model) KEY GRAPH 9-9 PAGE 191 is a tool to determine equilibrium GDP 15. Equilibrium Output is that output where the total quantity of goods produced (GDP) equals the total quantity of goods purchased (C + I). On the model, the 45 line shows potential GDP equilibria where C+I = GDP. 16. The actual equilibrium level of GDP is the GDP, which corresponds to the intersection of the aggregates expenditures schedule and the 45 line. KEY GRAPH 9-9 PAGE 191 17. Equilibrium GDP can be determined using the leakages-injections approach. FIGURE 9-10 PAGE 192 18. Savings is a leakage or withdrawal of spending from the income-expenditures stream whereas investment is an injection. At equilibrium GDP, where C + I = GDP, S = I (in a closed economy with no public sector). 19. Actual investment equals planned investment and unplanned investment (i.e. unplanned changes in inventory investment. Unplanned investment acts as a balancing item which equates the actual amounts saved and invested in any period. a) At all above-equilibrium points, where savings exceeds planned investment, inventories (i.e. unplanned investment) will rise until savings equal actual investment. Businesses will cut back on production until equilibrium (S = planned I) occurs. b) At all below-equilibrium points, where savings is less than planned investment, inventories (i.e. unplanned investment) will fall and businesses will increase production until equilibrium (S = planned I) occurs. c) Only at equilibrium does S = planned I and the unplanned investment is zero. Chapter 10: 1. Aggregate Expenditures: The Multiplier, Net Exports, and Government (Week 8) The multiplier effect is that a change in a component of aggregate expenditures leads to a larger change in equilibrium GDP. Multiplier = Change in real GDP Initial change in spending (C or I or G or Xn) Thus, the change in real GDP = multiplier x initial change in spending. The expenditure multiplier = 1 MPS or 1 1 – MPC 2. Net exports (Xn) = exports (X) – imports (M). Positive net exports (X > M) will increase aggregate expenditures whereas negative net exports (X < M) will decrease aggregate expenditures. FIGURE 10-4 PAGE 205 3. Increases in public or government spending (G) will increase aggregate expenditures whereas decreases in G will decrease aggregate expenditures. FIGURE 10-5 PAGE 209 4. Changes in taxes will have a smaller multiplied effect on equilibrium than the expenditure multiplier above because taxes initially change disposable income before affecting consumption. For example, if the government reduces taxes by a lump sum of $20 billion at all levels of disposable income and the MOC is 0.75, people will only spend $15 billion and save $5 billion. Thus, the multiplied effect would increase GDP by $60 billion ($15 billion x 4). Thus the tax multiplier is only 3. Contrast this to an increase in government spending by $20 billion which would increase GDP by $80 billion ($20 billion x 4). The tax multiplier = - MPC 1 – MPC 5. Equal increases in government spending and taxation increase the equilibrium GDP by the amount of the increase. If the government increased both taxes and spending money by $40 billion, equilibrium GDP would increase by $40 billion. If the MPC were 8, the government spending would increase equilibrium GDP by $200 billion ($40 billion x 8) whereas the increased lump sum tax of $40 billion would first lower disposable income by $32 billion ($40 billion x 0.8) and then reduce equilibrium GDP by $160 billion ($32 billion x 5). $200 billion - $160 = $40 billion. Government spending affects aggregate expenditures more powerfully than a tax change of the same size. The balanced budget multiplier = 1 6. A recessionary gap is the amount by which aggregate expenditures at the full-employment level GDP fall short of those required to achieve the full-employment GDP. If full employment GDP were $500 billion, and actual equilibrium GDP $400 billion and the MPC 0.8, aggregate expenditures would have to increase $20 billion ($100 billion/5) to solve the recessionary gap. KEY GRAPH 10-8 PAGE 214 7. An inflationary gap is the amount by which an economy’s aggregate expenditures at the full-employment GDP exceed those necessary to achieve the full-employment GDP. If full employment GDP were $500 and actual equilibrium GDP $750 billion and the MPC 0.9, aggregate expenditures would have to be reduced by $25 billion ($250/10) to solve the inflationary gap. KEY GRAPH 10-8 PAGE 214 Chapter 11: 1. Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply (Weeks 9-10) Aggregate Demand is a schedule or curve showing the various amounts of goods/services (i.e. real output) that domestic consumers, businesses, government, and foreign buyers collectively desire to purchase at each possible price level. There are three reasons for the downward slope of AD where a higher price level will decrease the quantity of real GDP demanded and a lower price level will increase the quantity of real GDP demanded. FIGURE 11-2 PAGE 224 wealth effect: a higher price level reduces the real value or purchasing power of the public’s accumulated financial assets b) interest – rate effect: a higher price level increases the demand for money and (assuming a fixed supply of money) raises the interest rate which reduces consumption and investment c) foreign purchasing effect: a higher price level makes U.S. exports relatively expensive and foreign imports relatively cheap reducing net exports (X – M) a component of aggregate demand a) 2. Determinants of aggregate demand will increase (shift right) or decrease (shift left) AD at all price levels. Factors that will increase AD include: a) consumption spending (increase in consumer wealth, expectations of future price increases, household debt and taxes – see explanation above) b) investment spending (decrease in rate, higher expected returns on investment, lower business taxes, new technology, excess capacity) c) government spending d) net export spending (rising foreign national income, depreciation of U.S. dollar) 3. Aggregate supply is a schedule or a curve showing the level of real domestic output, which will be produced, at each price level. There are three regions of the AS curve: a) horizontal or Keynesian b) upward sloping and c) vertical or classical. FIGURE 11-5 PAGE 228 4. Determinants of aggregate supply will increase (shift right) AS at all price levels. When per-unit costs decrease, aggregate supply will increase and when per-unit costs increase, AS will decrease. FIGURE 11-6 PAGE 230 Some aggregate supply determinants include: a) b) c) d) lower input prices (for labor, land and capital) will increase AS an appreciation of the dollar will lower the price of imported resources and increase AS increased productivity = total output/total inputs will lower costs and increase AS supply-side economic policies that lower business taxes will reduce costs and increase AS 5. The equilibrium price level and equilibrium real GDP occur where AD = AS. KEY GRAPH 11-7 PAGE 233 6. The effect of changes in AD on equilibrium price level and output depend upon which of the three ranges the shift in AD occurs. FIGURE 11-8 PAGE 235 If AD increased, the following table summarizes the effects: Range: Horizontal Intermediate Vertical Chapter 12: Price Level: no change moderate increase large increase Fiscal Policy Real GDP: large increase moderate increase no increase Multiplied Effect: full effect reduced effect none (Week 11) 1. Discretionary Fiscal Policy is the deliberate manipulation of taxes and government spend to alter GDP and employment, control inflation, and stimulate growth. 2. Stabilization Policies in the short run involve the following two options: a) Expansionary fiscal policy is used to eliminate a recessionary gap and stimulate AD in order to return the economy to full employment. b) Contractionary fiscal policy is used to counteract an inflationary gap and reduce AD in order to return the economy to full employment. 3. Fiscal Policy Options a) expansionary b) contractionary Gov’t Spending Taxes increase lower decrease raise Effect on GDP increase decrease Effect on Prices Effect on Budget increase toward deficit lower toward surplus effect on prices assumes in intermediate or vertical region of AS (horizontal, region, no change) 4. The crowding out effect is an argument that an expansionary fiscal policy (deficit spending) will increase the interest rate and reduce private investment, reducing the stimulus of the fiscal policy. FIGURE 12-7 PAGE 255 Specifically, here are the linkages: a) government spending and/or tax reduction increases the budget deficit b) the budget deficit is finance through government borrowing of funds in the money market c) the increase in the demand for money raises the interest rate d) the higher interest rate discourages or “crowds out” private investment e) economic growth in long run (LRAS) will be reduced due to smaller private capital stock 5. The net export effect further reduces the impact of expansionary fiscal policy as higher domestic interest rates: a) increase foreign demand for dollars b) the increased demand for dollars results in an appreciated dollar c) the appreciated dollar makes exports more expensive and imports cheaper d) net exports decline partially offsetting the expansionary fiscal policy 6. Non discretionary fiscal policy or built-in stabilizers are counter cyclical government programs (e.g. progressive income tax and transfer payments such as unemployment compensation) that automatically counteract both recessions and high inflation. a) For example, as GDP rises during prosperity, tax revenues under a progressive income tax system automatically increase and transfer payments such as unemployment insurance automatically decrease, both reducing consumer spending and restraining economic expansion. The budget will automatically move toward a surplus. b) Conversely, as GDP falls during a recession, tax revenues automatically decline and transfer payments automatically increase, stimulating consumer spending and preventing a prolonged recession. The budget will automatically move toward a deficit. Chapter 13: Money and Banking (Week 12) 1. 2. Money serves three functions: medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value. MI is the more liquid category of money and includes currency checkable deposits. 3. M2 includes MI and near monies (e.g. savings, time deposits, and money market mutual funds). 4. The purchasing power of money is the amount of goods/services money will buy. Higher prices lower the value of the dollar because more dollars will be needed to buy a particular amount of goods/services. 5. The public demands money for two reasons: to make purchases with it (transaction demand) and to hold it as an asset. KEY GRAPH 13-2 PAGE 273. The total demand curve for money includes two components: a) The assets demand for money varies inversely with the rate of interest. When the interest rate (i.e. the opportunity cost of holding money) is low, the public will choose to hold a large amount of money as assets whereas when the interest rate is high, people will hold less money as assets. Thus, the demand curve for money is downward sloping. b) The transactions demand for money varies directly with nominal GDP. If higher prices increase nominal GDP, the transaction demand for money will shift the total money demand curve to the right at all levels of interest. 6. Money market equilibrium curve: Change in $ supply: Increase Decrease No change No change Chapter 14: 1. occurs where the vertical supply curve of money intersects the downward sloping demand Change in $ Demand: no change no change increase decrease How Banks Create Money Change in Equilibrium Interest: decrease increase increase decrease (Week 13) A balance sheet is a statement of what the bank owns (assets) and what the bank owes (liabilities). Bank assets include cash reserves, bonds, and loans. Bank liabilities include demand deposits (checking) and savings accounts. 2. The Federal Reserve requires that banks keep a specified percentage of its own deposit liabilities on reserve The reserve ratio = Commercial bank’s required reserves Commercial bank’s demand-deposit liabilities 3. Excess reserves = actual reserves – required reserves 4. The money multiplier indicates the maximum amount of new demand-deposit money, which can be created in the banking system by a single dollar of excess reserves. As a formula, M= 1 R (where M = money multiplier and R = required reserve ratio) Maximum demand-deposit creation = excess reserves x m If, for example, the required reserve ratio was 0.2, $100 billion of excess reserves would multiply to $500 billion. Higher reserve ratios mean lower money multipliers and therefore cost less creation of new deposit money via loans whereas smaller reserve ratios mean higher money multipliers and thus more creation of new deposit money via loan. Two limitations that reduce the full effect of the money multiplier include: a) money received by a borrower may not be re-deposited in the banking system b) bankers may hold excess reserves above the required reserve ratio Chapter 15: 1. Monetary Policy (Week 14) Monetary policy consists of altering the economy’s money supplies to stabilize aggregate output, employment, and the price level. The three major tools of monetary policy and the effect on real GDP and price level. The three major tools of monetary policy include: a) Open market operations involves the buying and selling of government bonds (securities) by the Federal reserve Banks in the open market. Buying securities from banks and/or the public will increase bank reserves and thus the money supply. When the Fed buys government bonds the supply decreases, raising bond prices and lowering interest rates. Selling securities to banks and/or the public will decrease bank reserves and thus the money supply. When the Fed sells government bonds the supply increases, lowering bond prices and raising the interest rates. b) The reserve ratio: lowering the reserve ratio decreases the amount of required reserves banks must maintain increasing excess reserves and the money supply via new loans. Raising the reserve ratio increases the amount of required reserves banks must maintain decreasing excess reserves and the money supply. c) The discount rate is the interest rates the Fed charges commercial banks for loans. When the discount rate is decreased, commercial banks are encouraged to obtain additional reserves by borrowing from Fed Reserve Banks. 2. A tight or contractionary monetary policy is an attempt by the Fed to lower the supply of money in order to reduce spending and control inflation whereas an easy or expansionary monetary policy is an attempt to increase the supply of money in order to encourage spending and increase aggregate demand and employment. See chart below: See KEY GRAPH FIGURE 15-2 PAGE 314-315 3. The effectiveness of monetary policy depends upon the elasticity of the demand for money and the investment. The steeper (more elastic) the demand curve for money, the larger the effect of any change in the money supply on the equilibrium rate of interest. Furthermore, any change in the interest rate will have a larger impact on investment—and hence aggregate demand and GDP – the flatter (more elastic) the investment demand curve. 4. The net export effect of monetary policy, unlike fiscal policy, will increase net exports if expansionary and decrease net exports if contractionary. See chart below: Unit Activity: Take a trip to the Fed. Chapter 16: Chapter 17: Extending the Analysis of Aggregate Supply and Disputes in Macro Theory and Policy (Weeks 15-16) 1. The short-run is a period in which nominal wages (and other input prices) are fixed as the price level changes. The short run aggregate supply curve (SRAS) is upward sloping because if prices rise while nominal wages are fixed, profits rise and output will increases. If prices fall while nominal wages are fixed, profits fall and output will decrease. 2. The long run is a period in which nominal wages are fully responsive to changes in the price level. As a result, the long run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) is perfectly vertical (inelastic) as higher prices result in higher wages, and no change in output. Note that the LRAS is the production possibilities curve (PPF) in an economy. 3. Although aggregate demand and SRAS may intersect beyond the LRAS in the short run, economic growth only occurs when the LRAS shifts to the right due to increased productivity, lower input costs for business, new technology, etc. Classical Model Assumptions i) the economy operates at full-employment (Qf) where long run aggregate supply curve is vertical (LRAS) ii) wages, prices, and interest rates are fully flexible (long run assumption) iii) aggregate demand is relatively stable iv) if there is an inflationary or recessionary gap, the economy will self-correct without government intervention (laissez-faire) 4. A. Theory of Self-Correction Scenario A: Inflationary Gap (Model A on left) i) ii) iii) iv) AD increases from AD1 to AD2 In short run (SR) prices increase => revenue increases => profit increases (as nominal wages and other output costs are fixed in the short run) – real output increases (point b at Q2, PL2). In long run (LR) economy self-corrects as nominal wages and other input costs increase SRAS curve shifts left (AS2) => real output falls and returns to Qf and prices increase to PL3 (point c) B. Theory of Self-Correction Scenario B: Recessionary Gap (Model B on right) a) AD decreases from AD1 to AD3 b) In short run (SR) prices fall => revenue falls => profit falls (as nominal wages and other input costs are fixed in the short run) => real output falls (point d at Q3, PL4) c) In long run (LR) economy self-corrects as nominal wages and other input costs fall d) SRAS curve shifts right (AS3) => real output increases and returns to Qf and prices fall to PL5 (point e). 5. Keynesian Model Assumptions i) economy may operate below Qf in equilibrium for extended periods of time where AS is horizontal ii) prices, wages, and interest are often “sticky” iii) aggregate demand (especially investment) is volatile iv) government intervention (fiscal policy/monetary policy) manipulating aggregate demand is often necessary to help the economy reach and remain at full-employment (stabilization policies) A. Critique of Theory of Self-Correction Scenario B: Recessionary Gap (Model B on right above) i) AD falls from AD1 to AD3 ii) Prices downwardly inflexible and new temporary equilibrium where Pl1 intersects AD3 (point f) iii) Surpluses result as AS>AD iv) However the SRAS will not shift right to Qf (contrast classical view) because wages are so sticky. v) The economy will be “stuck” at point d with high unemployment, low RDGP and a recession vi) Expansionary fiscal and monetary prices will enable shift AD right and the economy will return to full employment 6. The Phillips Curve notes that high rates of inflation are accompanied by low rates of unemployment and low rates of inflation are accompanied by high rates of unemployment. Logic: if AD increases prices increase RGDP increases unemployment increase However, this inverse correlation between inflation and unemployment exists only in the short run due to the idea that the economy self-corrects and returns to full-employment. Refer to models below for each step: a) b) c) d) AD increases from AD to AD’ (equilibrium point A to point B) Inflation increases to 6%, but nominal wages remain fixed in short run at 4% => profits increase => In SR, RGDP rises, and the unemployment rate falls to 3% In LR, nominal wages will match prices and increase to 6% => SRAS will shift left (SRAS’) as profits fall e) In LR, output will be point C at full employment (Qf) with inflation at 9% a) b) c) d) e) AD decreases from AD to AD” (equilibrium point A to point D) Inflation decreases to3%, but nominal wages remain in short run at 4% => profits fall => In SR, RGDP falls, and the unemployment rate rises to 8% In LR, nominal wages will decrease to 3% => SRAS will shift right (SRAS”) as profits rise In LR, output will be point E at full employment (Qf) with inflation at 1% Note the following: Points: A B C D E Inflation: 4 6 9 3 1 Unemployment: 5 3 5 8 5 In the long run (points A, C, E) there is a natural rate of unemployment (NAIRU) where cyclical unemployment is zero and various rates of inflation occur, although the economy at full employment should generate a stable rate of inflation. Thus, whereas in the short run there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment, this inverse correlation does not exist in the long run if wages, prices, and interest are flexible. 7. Cost-Push Inflation or Stagflation The short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment due to AD changes will not exist with stagflation. Here an economy experiences both high inflation and unemployment. Stagflation is due to supply shocks that shift AS left (such as the quadrupling of oil prices, low productivity, and more stringent government regulations on business). Traditional fiscal and monetary tools that manipulate AD will be ineffective in returning the economy to full employment as expansionary policies will decrease unemployment but further increase inflation and contractionary policies will decrease inflation but further increase unemployment. 8. Non-Classical Schools of Economics A. Monetarism is based on the quantity theory of money (MV = PQ). According to the monetarists, changing the money supply can have some short-run effects on aggregate demand, but the only long-run effect is to change the price level. The level of long-run aggregate supply determines full employment. Output can only increase by 3-5% a year. Monetarists believe that increasing the money supply by 3-5% a year will allow economic growth to occur; increasing the money supply by more than 5% will just cause prices to increase; and increasing the money supply by less than 3% will cause output to decrease and a recession to result. This policy of expanding the money supply to match the growth of the LRAS is called the monetary rule. Equation of Exchange: MV = PQ (total amt. spent by purchasers of output = total amt. received by sellers) M = supply of money V = velocity of money (number of times per year the average dollar is spent) P = price level Nominal GDP Q = output Key assumption = V is stable. Therefore, there is a direct correlation between M and PQ (e.g. if V = 5 and M = $100 billion, then NGDP = $500. If the money supply (M) increases $10 billion, NGDP will increase $50 billion) Monetarists: 1. MV = PQ most important identity. Concerned primarily with the rate of growth of money supply and its effect on NGDP. Keynesians: 1. C + I + G + Xn most important identity. Concerned primarily with aggregate demand and its effect on RGDP. 2. Recessions/inflation are results of changes in 2. Recessions/inflation are the money supply that are lower/higher than constant result of changes in aggregate growth of 3 – 5%. demand (e.g. changes in savings rate, consumer/business confidence, net exports, govt taxes). 3. The economy operates normally at Qf and vertical LRAS. Therefore, increasing MS will increase AD but 3. The economy can be below Qf and increasing MS will lower only increases NGDP. interest rates, increase C and I and increase RGDP until full employment is reached. 4. If government engages in deficit spending during a 4. Deficit spending will not crowd recession by selling U.S. securities (borrowing money) out private investment during a interest rates will increase and more profitable investment recession because business will be crowded out. confidence is low and pressure on interest rates small. In fact, private despite higher interest rates, crowding in may occur. 5. The Fed can and should only fight inflation and adjust the money supply, not interest rates. 5. The Fed can and should Manipulate interest rates to increase/decrease investment AD. B. Rational Expectations School (RatEx) Key Assumptions i) Individuals base their forecasts or expectations about the future values of economic variables on all the available information past and present. ii) Businesses, consumers, and workers understand how fiscal/monetary policies will affect the economy and anticipate the impacts in their own decision making thereby making the intended policies impotent. iii) Economy operates at Qf with vertical LRAS/Phillips Curve. Example: If the Fed lowers interest rates to increase investment and aggregate demand, workers understand from past experiences and economic knowledge that inflation will increase. They anticipate higher prices and ask for an increase in nominal wages, which drives up prices and interest rates on loans. Thus, real output and employment do NOT change despite the good intentions of the Fed. On the Phillips Curve model above, the economy moves directly from point A to point C even in short run. Fiscal and monetary policies will only change prices (NGDP) not RGDP as all policies fully anticipated (unless there is an unannounced policy change and this is de stabilizing) C. Supply-Side School Changes in aggregate supply must be recognized as active forces in determining the levels of both inflation and unemployment. Specifically, certain government policies (tax regulation) have reduced the growth of aggregate supply in the long run. Increasing LRAS will reduce unemployment and inflation. i) ii) iii) Lowering marginal tax rates will increase the incentive to work more hours or enter the labor force, increase productivity, and result in more tax revenues. (Latter curve FIGURE 16-15) Lowering marginal tax rates will increase disposable income and thus savings, increasing the pool of money for investment (supply-siders also advocate lower taxes on investment income such as capital gains tax), thus increasing the capital stock and worker productivity. Reduce government regulation on business (e.g. environmental restrictions, affirmative action, and legal monopolies) in order to reduce costs and encourage an increase in aggregate supply. Chapter 18: 1. Economic Growth (Week 17) A nation’s real GDP in any year depends on the input of labor (measured in worker-hours) multiplied by labor productivity (measure as real output per worker per hour). FIGURE 18-1 AND 18-3 PAGES 370-371 As an equation, Total output = worker – hours x labor productivity 2. The major factors that will increase economic growth (expand the PPF or LRAS) include: a. b. c. d. e. increases in the quantity and quality of human resources (e.g. through education and training) increases in the quantity and quality of natural resources increases in the supply (or stock) of capital goods improvements in technology increase in economic efficiency Chapter 19: 1. Budget Deficits and the Public Debt (Week 17) a) A budget deficit is the amount by which government expenditures exceed its tax revenues in a particular year. For example, the 1998 federal budget had a surplus of $70 billion. b) The national or public debt is the total accumulation of the Federal government’s total deficits and surpluses, which have occurred through time. For example, the total federal debt is currently $5.4 trillion. Unit Activity: Research the National Debt-where did it come from? IV International Economics Chapter 37: 1. International Trade (Week 17) One country has an absolute advantage over another in the production of a particular good if it can produce that good using smaller quantities of resources than the other country. 2. According to the law of comparative advantage, one country has a comparative advantage over another in the production of a particular good relative to other goods if it produces that good least inefficiently as compared with the other country. If each country specializes in producing the good it does comparatively best (i.e. with the lowest opportunity cost), total output will be greatest overall. Output Question: Number of Apples and Oranges Produced Goods Apples Oranges Country A 50 100 Country B 10 40 Country A has an absolute advantage in both apples and oranges, but a comparative advantage in apples. The opportunity cost of producing 1 apple for Country A is 2 oranges whereas the opportunity cost of producing 1 apple for Country B is 4 oranges. The opportunity cost of producing 1 orange for Country A is ½ apple whereas the opportunity cost of producing 1 orange for Country B is 1/4 th apple. Thus, Country A should produce apples and Country B should produce oranges and each trade for the other. Input Question: Days to Produce Two Goods Goods Cars Airplanes Country A 8 days 10 days Country B 15 days 12 days Country A has an absolute advantage in both car and plane production, but a comparative advantage in car production. The opportunity cost of producing 1 car for Country A apple is 4/5 th plane whereas the opportunity cost of producing 1 car for Country B is 5/4th plane. The opportunity cost of producing 1 plane for country A is 5/4 th car whereas the opportunity cost of producing 1 plane for Country B is 4/5 th car. Thus, Country A should produce cars and Country B should produce planes. KEY FIGURE 37-2 PAGE 769 3. Through free trade and the principle of comparative advantage, the world economy can achieve a more productively and allocatively efficient allocation of resources and a higher level of material well being. 4. Two common trade barriers are tariffs, which are excise taxes on imported goods. A protective tariff is intended to protect domestic producers from foreign competition. An import quota is a legal limit on the amount of a good that may be imported. The effect of tariffs or quotas on free trade is exhibited in the graph below: --If an import quota of 30, for example, is imposed, exports and prices in the exporting country will fall while in the importing country imports fall while world prices rise. In this case, a $0.75 tariff would have achieved the same effect of limiting imports and raising prices with the government of the importing country collecting revenue. 5. Who wins and who loses from tariffs and quotas? a) Consumers in the importing country lose other way as both impose tariffs/quotas result in higher prices for products than before on both foreign and domestic production. b) Domestic producers not subject to the tariff or quotas are winners as they receive higher prices and expanded sales than before. c) All foreign producers are hurt by tariffs as the tax raises prices, but not profits (usurped by the importing country’s government) and reduce sales. With quotas, the exporters who manage to enter the market benefit from higher prices in the foreign market; however, all the exporting country’s firms are hurt at home as prices fall and output is restricted. d) The importing country’s government gains from the tariff revenue, which is a transfer payment that may reduce taxes or pay for other social programs. e) In theory, the world is hurt as foreign countries earn fewer dollars due to trade barriers and will buy fewer U.S. exports, reducing free trade and distorting comparative advantages that countries enjoy. Note that under free trade, world prices were lower and world production greater. f) Finally, the importer may be hurt when the exporter retaliates and imposes its own tariffs. Trade wars may result in an inefficient use of resources and sacrifice of comparative advantage of specialization and free trade. Chapter 38: Exchange Rates, the Balance of Payments, and Trade Deficits (Week 18) 1. A nation’s balance of payments shows all the payments a nation receives from foreign countries and all the payments it makes to them. TABLE 38-1 PAGE 792 2. U.S. trade in currently produced goods/services is called the current account. a) U.S. exports have a plus (+) sign because they are a credit; they create a foreign demand for dollars, and the fulfillment of this demand increases the supply of foreign currencies owned by U.S. banks and available to U.S. buyers. b) U.S. imports have a minus (-) sign because they are a debit; they create a domestic demand for foreign currencies and the fulfillment demand reduces the supplies of foreign currencies held by U.S. banks and available for U.S. consumers. c) The balance on the current account shows all debits and credits in the current account. Within this larger category is the trade balance (item 3) and balance on goods and services (item 6) TABLE 38-1 The capital account summarizes the flows of payments (financial capital) from the purchase or sale of real or financial assets. a) Foreign purchases of asset in the U.S. represent an impayment of foreign currencies and have a (+) sign. b) U.S. purchases of assets abroad represent an outpayment of foreign currencies from the U.S. and have a (-) sign. c) The balance on the capital account shows all debits and credits in the capital account. TABLE 38-1 3. 4. The official reserves are quantities of foreign currencies held by central banks and which can be drawn on to make up any net deficit in the combined current and capital account. TABLE 38-1 Through the mechanism of official reserves, the balance of payments will be zero. a) A drawing down of official reserves (which is shown as a positive official reserves entry in the balance of payments) measures a nation’s balance of payments deficit. b) A building up of official reserves (which is shown as a negative official reserves entry in the balance of payments) measures a nation’s balance of payments surplus. 5. Flexible or floating exchange rates are determined by supply and demand without government intervention. KEY GRAPH 38-3 PAGE 795 a) A nation’s currency is said to appreciate when exchange rates change so that a unit of its own currency can buy more units of foreign currency. Example: in January 1999, $1 = 10 peso or 1 peso = $0.10 If in June of 1999, $1 = 20 peso or 1 peso = $0.05 Then the dollar has appreciated relative to the Mexican peso i.e. the dollar can buy more Mexican peso. b) A nation’s currency is said to depreciate when exchange rates change so that a unit of its own currency can buy fewer units of foreign currency. In the above example, the peso has depreciated relative to the dollar. Note: if the dollar appreciates relative to the peso the peso must depreciate relative to the dollar. 6. Market Determines of Exchange Rates In general, in the supply and demand graph, a currency will appreciate if the demand for the currency increases or the supply of the currency decreases. A currency will depreciate if the demand for the currency decreases or the supply of the currency increases. The following are specific market determinants that will cause a currency to appreciate or depreciate. a) changes in product preferences: if consumers desire goods from a foreign country (e.g. avocados from Mexico) then exports will increase, demand for that country’s currency will increase and the foreign currency – peso – would appreciate. b) change in relative income (output effect): if the growth of a nation’s income exceeds that of another nation, then its currency depreciates. If the U.S. RGDP > Mexico’s RGDP => imports will increase => demand for foreign currency (peso) will increase => U.S. dollar depreciates c) relative price levels (price level effect): i) if U.S. prices rise faster than foreign prices => imports are relatively cheaper => imports will rise => demand for foreign currency (peso) will rise => U.S. dollar depreciates ii) if U.S. prices rise faster than foreign prices => U.S. exports are relatively expensive => exports will fall => demand for U.S. dollar will fall => U.S. dollar depreciates d) relative real interest rates (interest rate effect): If U.S. real interest rates increase, international investors seeking the highest rate of return for their investment will increase their demand for dollar-denominated assets, thereby increasing the demand for dollars in foreign exchange markets. Thus, the U.S. dollar will appreciate. If U.S. interest rates are relatively lower, the dollar will depreciate as foreigners demand fewer U.S. bonds. e) Speculation: Currency speculators will buy and sell currencies in the hope of reselling/repurchasing at a profit. If speculators feel a currency (e.g. peso) will depreciate (due to an unstable economy, forecast of a recession, etc.) those holding pesos will begin to convert them to dollars before they lose value increasing the supply of pesos and demand for dollars, thus depreciating the peso before the market forces begin. In many ways this is akin to a bank run or a stock market crash. 7. Flexible Exchange Rates and Balance of Payments If the demand for pesos increases, but the exchange rates are fixed at $0.10 = 1 peso, a balance of payment deficit (ab) will occur. U.S. consumers demand Qb pesos, but the supply is fixed at Qa. Thus, a shortage of pesos exists. With flexible exchange rates, the dollar would depreciate to the new equilibrium where $0.20 = 1 peso, imports would be more expensive and quantity demanded for Mexican imports would fall, resulting in less demand for pesos from Qb to Qc. See example below: Mexican t.v. at 2000 pesos would be $200 with an exchange rate of $0.10 = 1 peso. Mexican t.v. at 2000 pesos would be $400 with an exchange rate of $0.20 = 1 peso. At the same time, U.S. exports to Mexico would become cheaper if the dollar depreciated and quantity demanded for U.S. exports would rise, resulting in more supply of pesos from Qa to Qc. U.S. wine at $10 bottle would be 10 0 pesos with an exchange rate of $0.10 = 1 peso. U.S. wine at $10 bottle would be 50 pesos with an exchange rate of $0.20 = 1 peso. 8. Fixed Exchange Rates: a predetermined rate set by the government at which currencies are exchanged. In the above example, if the dollar were fixed at 1 peso = $0.10 or $1 = 10 peso after the demand for the peso increased, how could the U.S. maintain this over currency deficit? 1) use of official reserves of foreign currency (peso) accumulated over time or sell gold to Mexico in exchange for pesos in order to increase the supply of pesos to meet the higher demand. The problem is that if persistent deficits exist, a nation cannot maintain a fixed exchange rate as reserves become exhausted (especially, if speculators, sensing this inevitable depreciation of the dollar in this case, begin selling dollars for pesos). 2) The U.S. could respond to the shortage of dollars by discouraging imports (thereby reducing the demand for pesos) with trade barriers (tariffs/quotas) or encouraging exports (thereby increasing supply of pesos). 3) The U.S. could implement contractionary fiscal/monetary policies that would do the following: i) reduce income/RGDP => imports would fall => demand for dollars peso falls ii) reduce U.S. prices => Mexican imports would be more expensive => imports would fall => demand for pesos would fall => while exports to Mexico would be cheaper => exports would rise => supply of pesos would increase iii) higher interest rates => supply of pesos would increase as Mexican investors buy U.S. bonds 4) A devaluation is a reduction in the official value of a currency whereas a depreciation reflects the interaction of supply and demand. In this case, the U.S. government could officially devalue the dollar so that 1 peso = $0.20 or $1 = 5 pesos. Note: a revaluation is an increase in the official value of a currency (contrast with appreciation) Unit Activity: Research the exchange rate between the U.S. and another country-why is the dollar weak or strong? Appendix I: Term Paper Macroeconomics Term Paper Overview: This paper is designed to be a position paper on a contemporary macroeconomic issue. You are required to select an issue that has social significance in today’s society and take a stance on that issue using economic reasoning as the foundation of your argument. All research will be from sources no earlier than September 1, 2004 and will be properly cited. Article Analyses: You will be required to turn in 6 Article Analyses (1 per week) as the foundation for your paper. You will use the designated summary sheet, including each of the following: 1. Name of the article 2. Source of the article-including page number, website, or location of the article. 3. Date of the article 4. Is the source of the article in any way bias-why? 5. Summary a. What does the article say? b. Is the source credible? c. Do you agree or disagree with the article and why? d. How will you use the information for your paper? Research Paper: The paper will have 3 basic components: 1) A detailed description of the problem 2) A clear position about the issue 3) A recommendation to the government about how to handle the position. (Expansionary Fiscal Policy, Contractionary Monetary Policy e.g.) Requirements: Typed 5-6 pages Bibliography Title Page 9 Sources (Including 6 Article Analyses) Grading: Topic: Article and Analysis: Title Page: Bibliography: Term Paper: Total Points: 5 points 5 points each (30 points) 5 points 10 points 50 points 100 points