Document 17576767

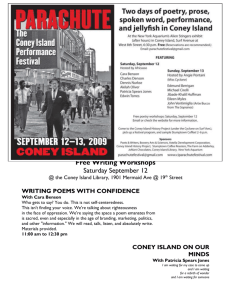

advertisement

Name P e r i o d i s e 2 9 A Coney Island D a t e E x e r c Steeplechase Park Opens The first of the great Coney Island parks, Steeplechase Park, was the work of George C. Tilyou, and it grew from the sprig of envy. A local since childhood and proprietor of the Surf Theater at Coney Island, Tilyou visited the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago on his honeymoon and was awestruck by the Ferris Wheel, which debuted 1 there. Unable to procure the wheel for himself , as it had already been sold, he contracted the Pennsylvania Steel Company to build another one expressly for him. Tilyou's Ferris Wheel rose from a plot of land on the Bowery and West Eighth Street, near Culver's Iron Tower. After covering it with incandescent lights and billing it as the largest in the world (though this claim was plainly untrue), he had his sister Kathryn sit behind the cash register wearing their mother's diamond necklace. For maximum effect, two strong men stood beside Figure 1: The "Funny Face" entrance to Steeplechase. her, as if to protect the jewels from thieves. The Ferris Wheel opened for business in the spring of 1894 and paid for itself within a few weeks. Although Tilyou owned a number of other rides, they were scattered around Coney Island until 1895, when Captain Paul Boyton inaugurated his enclosed Sea-Lion Park. Taking that as his cue, Tilyou opened Steeplechase Park, with its leering "funny face" logo, on a 15-acre plot of oceanfront land and began looking for attractions to fill it. Since horse racing was easily the most popular diversion at Coney Island, Tilyou procured a mechanical race course, devised by the British inventor J.W. Cawdry, at a cost of $41,000. The Steeplechase Horses, as Tilyou called the ride, soon became synonymous with Coney Island. Six double-saddled mechanical horses took passengers down 1,100 feet of undulating track, over a stream bed and a series of hurdles, all around the outside of the park. The tracks ran abreast, simulating a horse race in which gravity gave the heavier riders the advantage. Always the master of effect, Tilyou dressed his attendants as jockeys and announced the start of each ride with a bugle. In 1902 Tilyou engaged Frederic Thompson and Elmer "Skip" Dundy to bring their "Trip to the Moon" ride from the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition. After one season at Steeplechase, they broke off to create vastly more ambitious Luna Park, but Tilyou managed to develop his own niche nonetheless. A trip to Steeplechase in its prime resembled a journey inside a gigantic pinball machine. If visitors made it through the Barrel of Love, a tunnel that turned beneath their feet, they would then be faced with the perplexities of the Earthquake Stairway, the Whichway and countless other conundrums inside the Pavilion of Figure 2: A couple enjoying the Steeplechase Coaster. Fun. The Human Roulette Wheel spun until passengers sitting on it were flung to the perimeter. The Human Pool Table presented a series of spinning discs that challenged the customer to cross from one side to the other without being seriously diverted. 1 Directly from George Ferris, the wheel’s inventor. Steeplechase had its share of surprises as well. Visitors to the Human Zoo descended a spiral staircase until they found themselves in a cage, where they were offered peanuts and monkey talk. The Blowhole Theater, located at the exit of the Steeplechase ride, forced unwitting women to stand above an opening that blasted air up their skirts while the crowd--generally recent victims themselves--looked on with approval. If a woman's escort protested, he often received an electric shock from a clown waiting nearby. 2 In 1907 Steeplechase was ravaged by fire. Undaunted, Tilyou charged admission to the burning ruins and immediately began building anew. The fire that razed Dreamland in 1911 left Steeplechase virtually unscathed, but George Tilyou died in 1914, and by then Coney Island as a whole was beginning to slip out of step with the times. Nevertheless, the park continued to operate until 1964, making it easily the longest running amusement enterprise in the history of Coney Island. When the park closed, there was talk of designating the Pavilion of Fun as a historical landmark, but real-estate developer Fred C. Trump had it demolished before a ruling could be made. Today, the last sign that Steeplechase Park ever existed is the defunct Parachute Jump, purchased in 1940 from James H. Strong, a retired naval officer who originally had it built to train real-life paratroopers for service. Luna Park Opens While the three great parks at Coney Island shared many characteristics, Luna Park, with its whimsical architecture and its commitment to a 3 complete fantasy world in which visitors could lose themselves, represented something entirely new in its day . The geniuses behind Luna Park, Frederic Thompson and Elmer "Skip" Dundy, forged their partnership at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo with Thompson's "Trip to the Moon" illusion ride. Lured to Coney Island by George C. Tilyou, the pair ran this ride and several others at his Steeplechase Park during the 1902 season. At the end of the summer, Tilyou offered them a lower percentage of the take for the following season. They declined the offer and instead bought up Captain Paul Boyton's Sea-Lion Park, intent on creating an amusement park of their own. When Luna Park opened on May 16, 1903, it was unlike anything anyone had ever seen. Thompson, an erratically trained architect, had designed an environment entirely at odds with the Beaux-Arts movement of the time. The lines, colors, and shapes were constantly changing. Rather than the usual central tower, there were spires and minarets everywhere. And it was immense. By 1907 Luna Park employed some 1,700 people and was illuminated by 1,300,000 electric lights, at a cost of $5,600 a week. Almost a municipality in itself, it had its own telegraph office, radio office, and long-distance telephone service. Inside this city within a city, worlds collided. Extending their success with illusion rides, Thompson and Dundy filled their park with visions of exotic events and locales, such as "The War of the Worlds," "The Kansas Cyclone," and of course, the ever popular "Trip to the Moon." The park itself was designed so as to keep visitors constantly on the move. If Dundy saw visitors so much as sitting down for a rest, he Figure 3: The entrance to Luna Park. would send a group of musicians over to get them back on their feet. With Steeplechase Park and Luna Park operating at full tilt, the momentum was overwhelming, and in 1904, Senator William Reynolds and a group of speculators opened Coney Island's third large-scale park. Although Dreamland was generally not as inventive as Luna Park, it did do well with morality plays, such as "The End of the World" and the Orient Theater's "Feast of Beshazzar and the Destruction of Babylon." Another of its popular attractions was Lilliputia, a miniature village populated by very small people, created and run from 1904 to 1906 by Samuel Gumpertz, who later became Dreamland's general manager. 2 Admission cost 10¢. The entrance to Lost Kennywood was created from the Luna Park entrance. 3 4 On opening day of the 1911 season, a fire broke out in Hell Gate and soon ran out of control, leaving Dreamland in cinders. The same thing had happened to Steeplechase Park in 1907 and George Tilyou had rebuilt it without thinking twice, but the owners of Dreamland, unlike Tilyou, had not grown up with Coney Island sand in their shoes, and they decided to cut their losses. Within a few years, Tilyou died and Frederic Thompson, operating alone since the death of Dundy in 1907, was forced to file for bankruptcy. Coney Island had appeared in the world with a burst of imagination, but its most extravagant days were already behind it. Coney Island Parks Closing With the coming of the Depression, Coney Island fell on hard times. People were less likely to spend money on extravagances, and when they did, movies were closer at hand. Nor did people have cross the world to get the Coney Island Experience: the original had inspired imitators that, if not as grandiose as Luna Park or Dreamland, were not so very different from the Coney Island of the 1930s. After the first heady days, the Electric Eden was finding its equilibrium in the larger scheme of things. Adversity continued to dog Coney Island even after the economy improved. The 1939 World's Fair in New York was perceived as a beacon of hope by the general populace, but from the perspective of amusement proprietors, it only stole customers away. Moving several of the World's Fair attractions, such as the Parachute Jump, to Coney only helped for a while. During World War Two, the "lights out" policy dimmed the resplendent electrical aura that had always been its calling card, and the fun seemed to go out of Coney Island. Although Luna Park struggled along through these times, it had plainly been deteriorating. Then Coney Island's perennial curse of fire struck, not once but four times. The first blaze broke out before the 1944 season had begun, partially destroying LaMarcus Thompson's Scenic Railway roller coaster and the Figure 4: Two ladies enjoy a Luna attraction. Tunnel of Love beneath it. Damp weather and lack of wind limited the damages, but on August 12 a second fire started in the washroom of the Dragon's Gorge, another classic roller coaster, and eventually spread to much of the park. For the remainder of the season, only the western half of Luna Park remained open. Then it closed, and an insurance battle commenced. In 1946 the property was sold to new owners, who planned to build a housing project. Before they could do so, two more fires took down everything that remained of Luna Park except the ballroom and the pool, which then had to be demolished the old-fashioned way. F i g u r e 5 : T h e Foolish House at Dreamland Park. Post-war Coney Island suffered from a competitor that was perhaps even more formidable than the rest: the automobile. Steeplechase continued bravely onward, but interest had clearly turned elsewhere. The various freak shows that had prospered after World War One began to lose customers as well, and to move out of Coney Island. As more and more housing projects were built behind Surf Avenue, the neighborhood took on an increasingly rough character. In this context, the various electric shocks administered at Steeplechase no longer seemed so funny, and customers began to complain. In the midst of family squabbles, the last of the great parks closed in 1964. Coney Island was not dead. Another park, Astroland, opened in 1962 and was able to stay in business despite all predictions to the contrary. The Cyclone roller coaster continued to take brave souls on its terrifying course, and the Wonder Wheel, with its design dating back to the early 20th century, still lifted lovers to a bird's eye view of sea and sand. - Excerpt from PBS.com 4 Due to electrical problems.