Bridging Boundaries for Collaborative Ends MSU ADVANCEnetwork Science in the Public Interest

advertisement

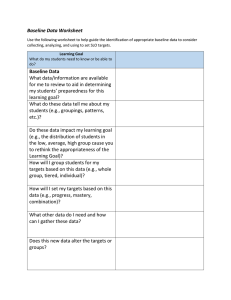

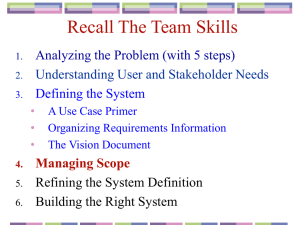

MSU ADVANCEnetwork Science in the Public Interest Bridging Boundaries for Collaborative Ends Laura J. Black, Ph.D., Montana State University Siobhan O’Mahony, UC Davis GSM May 4, 2009 Overview: The Beauty of Sharing REALLY Bad Drafts Why collaborating is hard Research: Reducing “disconnects” in large space system development programs Summary of findings ******* Guidelines for practice 2 Why Collaborating Is Hard (at least one important reason) Working Across Boundaries What happens when expertise differs? How do we THINK together? 4 4 Knowledge: Not JUST in Our Heads Knowledge is DISTRIBUTED across… …our ACTIVITIES …our THINKING… …and the LOCATIONS where we use the TOOLS and PROCESSES we need to think and work. 5 5 Knowledge—Not JUST in Our Heads Remove any one of these… …our THINKING …the LOCATIONS with situated TOOLS and PROCESSES …our ACTIVITIES …and we know LESS 6 6 Research: “Disconnects” in Large Aerospace Programs Empirical Background Aerospace acquisition—very large product development using technologies in new ways Congressional authority, changing stakeholders No chance to to learn from mistakes Requirement to integrate expertise across Geographic settings Disciplinary boundaries Organizational lines Society sectors 8 Presenting Research Problem How can we “stay on the same page” as we do this long-horizon innovative work? How can we reduce "disconnects" between the System Program Office and the prime contractor? “Disconnects”: Latent differences in understanding that can negatively affect the program if they remain undetected or unresolved. 9 9 Research Approach Conduct semi-structured and open-ended interviews in System Program Office Causes of disconnects Ways to reduce disconnects, stay "on the same page" Qualitatively analyze data to identify themes and distill constructs Construct simulation model of causal relationships to test competing explanations 10 What the SPO said… “We need people who can WRITE requirements.” “Poor Lt.Col. S—he didn’t know what the contractor gave him was crap.” “It takes the integrated product teams a long time to understand the consequence of a proposed change.” “The Engineering Change Board is too slow—by the time a change is approved, the contractor’s understanding of the change has changed.” “The problem is that requirements keep changing— even entire stakeholder groups change.” 11 Competing Explanations …people can't communicate …the SPO lacks expertise …people are TOO SLOW in making sense of proposed changes …people (esp. in the SPO) are TOO SLOW to act …shifting requirements cause disconnects 12 Modeling SPO-Contractor Interactions System Program Office (SPO) Decide Act Orient Observe Observe Orient Act Decide KTR = Contractor SPO = System Program Office Contractor (KTR) 13 13 Modeling Chain of Interactions 4-player "intellectual supply chain" SPO, Contractor, Subcontractor, Vendor Baseline: organization's collective understanding of work-to-be-done Technical, financial, schedule baselines 14 What causes disconnects? Requirement Requirement <Requirement CHANGING <Requirement <Requirement Changes to Changes REQUIREMENTS Switch Changes Changes toBaseline> Baseline> to Changes to Baseline> Baseline Initial Baseline Baseline Decision and Decision andand Decision and DELAYS IN Delay DECIDING Decision Action Action Delay Action Delay Action Delay AND ACTING DELAYSand IN Observation and Observation Observation and Observation and OBSERVING AND Orientation Delay Orientation Delay Orientation Delay Orientation Delay ORIENTING Baseline Baseline Baseline Baseline Adjusting Adjusting Adjusting Adjusting Baseline Baseline Baseline Baseline Perceived Perceived Perceived Perceived Baseline Baseline Baseline Baseline •SPO •Contractor •Sub-Contractor •Vendor ClarityofofBaseline Baseline Clarity Clarity of Baseline Clarity of Baseline COMMUNICATION Communication Sent Communication Sent Communication Sent Communication Sent CLARITY EXPERTISE— AFFECTING Orientation Orientation Orientation Orientation ORIENTATION Expertise Level Expertise Level Expertise Level Expertise Level 15 15 What causes disconnects? Requirement Requirement <Requirement <Requirement <Requirement Changes to Changes Switch Changes Changes toBaseline> Baseline> to Changes to Baseline> Baseline Initial Baseline Baseline Decisionand and Decision Decision and Decision and Action Delay Action Delay Action Delay Action Delay Observationand and Observation Observation and Observation and Orientation Delay Orientation Delay Orientation Delay Orientation Delay Baseline Baseline Baseline Baseline Adjusting Adjusting Adjusting Adjusting Baseline Baseline Baseline Baseline Perceived Perceived Perceived Perceived Baseline Baseline Baseline Baseline •SPO •Contractor •Sub-Contractor •Vendor ClarityofofBaseline Baseline Clarity Clarity of Baseline Clarity of Baseline Communication Sent Communication Sent Communication Sent Communication Sent Orientation Orientation Orientation Orientation Expertise Level Expertise Level Expertise Level Expertise Level 16 16 Simulation Base Case Government and Contractor Baselines 200 150 100 50 0 0 6 12 18 24 30 Months SPO Baseline KTR Baseline SUB Baseline VEN Baseline 36 42 48 54 60 Widgets Widgets Widgets Widgets Disconnect index 2529 17 17 Simulated Scenario: Turning Off the “Requirements Grenade” Explanation: Disconnects arise from “out there”— because external stakeholders change requirements Scenario: Turn the Requirement Changes Switch “off” (no party receives external requirements changes) <Requirement Changes to Baseline> Baseline Decision and Action Delay Observation and Orientation Delay Adjusting Baseline Perceived Baseline Clarity of Baseline Communication Sent Orientation Expertise Level 18 18 Simulated Scenario: Turning Off the “Requirements Grenade” Government and Contractor Baselines 200 150 100 50 0 0 6 12 18 24 30 Months SPO Baseline KTR Baseline SUB Baseline VEN Baseline 36 42 48 54 60 Widgets Widgets Widgets Widgets Disconnect index 2288—only a 9.5% improvement 19 19 Simulated Scenario: Speeding Up the SPO Explanation: If the SPO oriented and acted more quickly, fewer disconnects would result Scenario Speeding-1: Reduces the SPO’s decision and action delay from 5 months to 1 Scenario Speeding-2: Reduces the SPO’s observation and orientation delay from 5 months to 1 <Requirement Changes to Baseline> Baseline Decision and Action Delay Observation and Orientation Delay Adjusting Baseline Perceived Baseline Clarity of Baseline Communication Sent Orientation Expertise Level 20 20 Simulated Scenario Speeding-1: Speeding Up the SPO–Accelerating Decision and Action Government and Contractor Baselines 200 150 100 50 0 0 6 12 18 24 30 Months SPO Baseline KTR Baseline SUB Baseline VEN Baseline 36 42 48 54 60 Widgets Widgets Widgets Widgets Disconnect index 2635—a 4.2% deterioration 21 21 Simulated Scenario Speeding-2: Speeding Up the SPO–Accelerating Observation and Orientation Government and Contractor Baselines 200 150 100 50 0 0 6 12 18 24 30 Months SPO Baseline KTR Baseline SUB Baseline VEN Baseline 36 42 48 54 60 Widgets Widgets Widgets Widgets Disconnect index 1918—a 24.1% improvement 22 22 What We Learned About Disconnects Disconnects …do not result from big changes from “out there” …are good, if you have confidence you can rapidly assimilate their implications …cause changes that, when “open” too long, spawn exponentially more follow-on changes! 23 23 How to Stay on the Same Page Increase expertise Put the best people on the project at the start Design socially constructed resolutions as well as technically designed solutions Iterating more times, more quickly, on lessperfect information produces better outcomes 24 How to Stay on the Same Page Orient 5 to 8 times for every big act! Cycle through the OODA loop more times but with less drastic action each time Each time you communicate, use some kind of representation! "How do I know what I think until I see what I say?" Remember, knowledge isn't JUST all in our heads—we need to see and touch things to "know" Use your representations as “boundary objects” 25 How to Stay on the Same Page Boundary objects: Artifacts enabling people to collaborate effectively across some boundary Open to multiple interpretations by each party Representing key dependencies among players Hiding a lot of details—"Impoverished replicas” of the salient shared dependencies To be a boundary object (not a bludgeoning tool) the artifact must be transformable by all parties 26 26 Why “Boundary Objects” Help Leverage points in the simulated world <Requirement Changes to Baseline> Helps shorten the time to understand changes Baseline Decision and Action Delay Observation and Orientation Delay Helps compensate for low expertise levels and leverages high expertise levels Adjusting Baseline Perceived Baseline Helps compensate for differences in organizations, relative expertise, knowledge domains, timing and location of collaborators Clarity of Baseline Communication Sent Orientation Expertise Level 27 27 Enabling Cumulative Innovation Through Collaboration with Unexpected Allies Siobhan O’Mahony UC Davis GSM ADVANCEnetwork “Science in the Public Interest” Montana State University May 4, 2009 Overview • The conditions that enable or hinder cumulative innovation • 2 in depth examples of unexpected allies learning to collaborate: – The case of open source vs industry – The case of Dupont vs academia • Principles for fostering collaboration with unexpected allies – to achieve cumulative innovation Cumulative Innovation • Cumulative innovation: repurposing or recombining pre-existing ideas to foster new innovations (adapted from Scotchmer, 1991, 2005). • Assumption: Recombinatory processes are not inherent to an innovation itself. They are inherently behavioral and shaped by the institutions in which they are embedded (Mokyr, 2004; Murray and O’Mahony, 2007) Institutions Supporting Cumulative Innovation are Under-theorized • Organizational scholars have studied what affects the structure and flow of knowledge • However, for innovation to occur, knowledge must not just flow; it must be understood and recombined in new ways • However, we know little about the social or institutional factors that affect an innovator’s ability or willingness to recombine knowledge. What Enables Cumulative Innovation? 1. Disclosure – to build on pre-existing knowledge one must know of it 2. Accessibility – to use knowledge developed by others, one must have access to make use of it 3. Validation – one must be able to replicate and validate prior knowledge to make use of it (Murray and O’Mahony, 2007) The over-riding research question: What role do organizations and institutions play in enabling or inhibiting these conditions? Cumulative Innovation: Informal and Formal Mechanisms Antecedents Informal Formal Disclosure Publications, research communities, conferences Patent filings, NDAs, Trade secrets Accessibility References, source code, Licenses, patent material libraries commons, open licenses, standards, cell banks Validation Peer review systems, Patent examiners, cell academic norms banks, encourage replication and falsification The cumulative perspective shifts attention from ‘who knows who?’ to ‘who can share, build upon and reuse knowledge?’ and, most importantly, ‘under what conditions?’ Case #1: Open Source vs Industry from: O’Mahony & Bechky, 2008 The “Linux Uprising” did not happen by the community alone. Some firms played an important role. Yet, open source communities were challenging the proprietary model of software development. How did these unexpected allies ever collaborate? Divergent Interests OS Projects Maintain communal form: informal collegial project practices and working norms Firms Influence project direction to align with firm strategy and time table Maintain individual technical autonomy Acquire more predictability in the software development process to foster firm planning Preserve transparency and open access to code development, in order to foster full participation in community decision-making Pursue partnership and collaboration opportunities with discretion Sustain project’s vendor independence Establish governance mechanisms to shape a project’s future But areas of mutual interest also existed…. “Commercial interests brought in a lot of problems that did not use to be there, like new interesting technical problems, like what do you do with terabyte disks and large scale clustering? Things that many technical people are kind of interested in but they never get to actually play with… For example, there’s a lot of people who are interested in doing performance work on extreme loads and the only place where that actually happens is the commercial setting” (Founder, Linux kernel project) Convergent Interests OS Projects Firms Enhance technical capability, performance and portability of software for use in the enterprise Acquire access to technical expertise and improve recruitment of skilled programmers Improve individual skill through exposure to new commercial performance challenges Collaborate with skilled experts to solve difficult technical problems; learn how source code can be customized to solve customer problems Achieve commercial legitimacy and recognition – establish traditional marketing channels Alleviate power of industry monopoly and enhance their own market share Enhance project’s market share and diffusion Increased margins through reduced licensing fees Domains of Adaptation Communities and Firms adapted their organizing practices in these four areas and reinforced them with the creation of boundary organization: 1. 2. 3. 4. Governance Membership Ownership Control Over Production Boundary Organizations • Boundary objects can help translation across different knowledge sharing communities • Boundary organizations facilitate collaboration between scientists and non-scientists by remaining accountable to both – Are often created through legislation to bridge science and politics • “Boundary organizations..involve people from both communities but play a distinctive role that would be difficult or impossible for organizations in either community to play” (Scott, 2000: 15). 1) Governance • Creating a Project Representation – “If [this] had been all over the newspaper…then Sun may never had adopted [GUI desktop project] because they would say, “Well we can’t do this. We can’t talk to these guys without being in the public eye, therefore we cannot have exploratory conversations. Therefore we cannot do business with them, right?” • Preserving Pluralistic Control – “This is about openness and democracy and no corporate influence poisoning the whole thing….Some of them are pretty heavy handed, some of these folks are saying things like, ‘if we don’t have a board member, we will not join this movement. We must be on the board of directors.”...I’m not sure that our hacker community is ready for that.” 1) Governance Interests Satisfied Organizing Practices Adapted Open Source Software Projects Firms Creating project representation Provides open access and participatory processes Reduces ambiguity and provides some degree of discretion Preserving pluralistic control Ensures independent & collective control without undue firm influence Provides some voice on project direction without direct control 2) Membership Defining Rights of Members - “What we were trying to do as a Foundation is have our own entity that could be on an equal footing with these companies, that could represent the community interests, right?” Sponsoring Contributors – “They understood this effectively that you know [Webserver Project] was not an industry consortium, right? It was a collection of individuals, so when an individual [Fortune 500 Firm] engineer got core commit access, if that individual left and went somewhere else to work on [the project], they would still have the same status within [the project].” 2) Membership Organizing Practices Adapted Defining Rights of Members Sponsoring Contributors Interests Satisfied Open Source Software Projects Firms Preserves individual basis of membership and independence of the community Firms cannot gain formal rights, only sponsor contributors Provides additional resources to help project improve Offers firms a means of direct access to development process 3) Ownership • Obtaining Work Assignment Rights – “I looked at it and said no I am not going to sign. And we changed like five words. And basically it was adding an ‘except for Linux’.” • Developing Contribution Agreements –At one Webserver Project meeting, members debated whether sponsored contributors should submit a disclaimer from their employers in addition to contribution agreements. • Managing Code Donation - “When Sun and IBM donated code to us, they signed contracts that said we sign over copyright… we can consider that our code. And thus the [project] Foundation is liable for it.” 3) Ownership Organizing Practices Adapted Obtaining Work Assignment Rights Developing Contribution Agreements Managing Code Donation Interests Satisfied Open Source Software Projects Firms Reinforces individual autonomy and independence Ensures clear provenance of code Ensures clear provenance of code, preserves access Ensures clear provenance of code, preserves access Enhances technical quality and reach of the project Improves efficiency from having to manage separate code base 4) Control of Production Community Control of Code Contribution - “The challenge we have is.. to figure out a way to keep the power with the hackers and provide an environment where players like Sun Microsystems or IBM or Compaq or smaller companies can be part of this [open source]” Managing Technical Direction – “This is a public project. The goals for that are discussed in public, they're made by, the community…And so that's not controlled by any company” 4) Control of Production Organizing Practices Adapted Community Control of Code Contribution Managing Technical Direction Interests Satisfied Open Source Software Projects Firms Allows community to preserve autonomy and independence Allows firms visibility into code development & access through sponsored contributors Allows community to preserve autonomy and independence Firms have informal influence on code development through sponsored contributors The Emergent Triadic Role Structure Open Source Communities • Retain their technical autonomy Boundary Organizations (Non-Profit Foundations) • Continue to make technical decisions through peer review • Hold the community’s assets & intellectual property rights • Retain a controlling interest on governance issues • Mediate corporate interests where relevant Firms • • Support projects May try to influence technical priorities • Do not obtain direct decision making or ownership rights • May use community work for profit with proper acknolwedgement Case #2: Dupont vs academia From: Murray, 2009 The Creation of the Oncomouse • 1984 Phil Leder & Tim Stewart, Harvard University, develop the “Oncomouse • First mouse with specific genes inserted that predispose the mouse to cancer – an important advance to understand the role of genes in cancer • Files patent application July 1984 • Publishes findings in Cell October 1984 • Patent granted to Harvard 1988- -US Patent # 4,736,866 - licensed exclusively to DuPont • Mouse is distributed thru suppliers but DuPont places licensing restrictions – “Reach-through” rights, extend to all derived works – “Article review” of all related publications Academic Reaction & Response • DuPont’s ‘reach-through’ rights ignite an uproar among scientists (Science, 1993) – imposes “normative transaction costs” on scientists (Murray 2005) • NIH recruits a non-profit facility (Jackson Laboratory) to be a repository for genetically altered mice and act as “boundary organization” between community and commercial interests • NIH, under Varmus, negotiates new terms with duPont to triage: – limit ‘reach-through’ rights for research – retain them for commercial purposes • Firms must buy a commercial license • Scientific norms and practices “trump” imposition of private interests in order to further cumulative research The Role of Boundary Organizations • • Boundary organizations can organize parties around common innovation needs without compromising divergent interests They enable collaboration not by blurring boundaries, but by reinforcing shared interests and delineating where interests diverge • Only by preserving the boundaries that separated parties with diverging interests could boundary organizations sustain their ability to represent either party. • Thus, their job is not to collapse divergent social worlds but to preserve and bridge them. Collaborating with Unexpected Allies • Collaborators do not need to maintain a full set of shared interests • Collaborators do not need to change their divergent interests – but must parse among these – – think triage between the interests of academia and industry 1. 2. 3. 4. Indentify the zone of shared interests for cumulative innovation Recognize shared interests alone are not enough – Adaptation of practices is required which may change collaborator role structures A new organization may be required to preserve actors ability to pursue divergent interests Breakout Discussion 1. What kinds of things do you collaborate on? 2. Where do these collaborations work well or break down? 3. Are these factors more likely to be internally or externally driven? 4. Have you collaborated with people that do not share your interests? Under what circumstances does this work? 5. Have you worked with a boundary organization before? Consider This…. Of 4,227 life scientists over 30 years, women faculty patented their work at 40% the rate of men – holding productivity, social network, scientific field and employer characteristics constant (Ding et al, 2006) – Patents are often an avenue to many types of rewards and recognition, consulting, advisory boards – Male patent holders typically have higher paper counts, more NIH money, and more coauthorships with industry scientists Why these Gender Differences? • The “Larry Summers” explanation - women do research that is less commercially relevant – No – citation impact across gender not significant • The “too busy” explanation – women are too busy publishing and balancing family • The network explanation – women lack contacts with industry – industry contacts were often precursor for patenting for men • The “ambivalence” explanation- concern that engaging with the commercial sector might create negative signal value Food for Thought Who are you not collaborating with that could be beneficial? Guidelines for Practice The Beauty of Sharing REALLY Bad Drafts Guidelines for Practice The enacted strategy is in people's heads. We can socially construct understanding to Build individual and collective chains of agreements Anchor intangible agreements with tangible artifacts We can manage OODA-loop pacing deliberately 5 to 8 iterations to stabilize a draft! The drafts have to be BAD because it's too costly to make them good. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OCI-0838317. 61 Guidelines for Practice Deliberately socially construct shared understanding Facilitate—(open, narrow, close) Communicate Plan to iterate Establish and manage pacing Use ugly, public representations Persist This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OCI-0838317. 62 The Shape of a Good Facilitation Summary: Make a mess…and clean it up! 63 Example of Social Construction Around 1945, Duncan Hines and other companies introduced instant cake mixes …just add water! THEY DID NOT SELL! Why? Housewives indicated that just adding water degraded role as family baker—that wasn't real baking Duncan Hines adjusted formulation …now must add an egg! Result: Sales took off 64 Planning to Iterate Are we talking to relevant stakeholders in the timeframe they/we want? Consider "sponsors" as well as "collaborators" Is iteration included in the work design? Are there many small agreements rather than one agreement "big bang"? How do the interim deliverables (artifacts) support the socially construction of our work? 65 Pacing the Iteration Is the pacing fast enough to prevent being “overcome by events”? The faster the environment is changing, the faster your OODA cycles must be. Does the plan include opening-out, narrowing, and closing activities? For EACH deliverable? For the effort? This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OCI-0838317. 66 Represent Work-In-Process Visually Visual artifacts always trail the non-observable development of understanding Visual representations help people recall Where they have been and What they have agreed upon to this point This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OCI-0838317. 67 Example of a REALLY Bad Draft 68 Example of REALLY Bad Draft 69 Example of REALLY Bad Draft 70 Example of REALLY Bad Draft 71 Share the Ugly Drafts Ugly documents invite “fixing” Beautiful documents look finished and "correct" Keeping it ugly until the end invites modification Iterating faster with ugly drafts Produces better results than slow "perfection" Is more effective at socially constructing agreements Time-boxes work and makes it easier to manage along the way Keeps costs low enough to iterate some more This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OCI-0838317. 72 Why Ugly Is Really Beautiful Iterating with ugly drafts builds “buy-in” Surfaces assumptions embedded in expertise Provides more cues for our distributed cognition Ugly drafts leave room for others to "add their egg"—creates true ownership in outcomes Shared ownership and understanding is key to “uncontrolled” joint action This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OCI-0838317. 73 Additional Resources • F. Murray (forthcoming). "The Oncomouse that Roared: Hybrid Exchange Strategies as a Source of Productive Tension at The Boundary Of Overlapping Institutions". American Journal of Sociology. • O’Mahony, Siobhán and Beth Bechky. 2008. “Boundary Organizations: Enabling Collaboration Among Unexpected Allies,” Administrative Science Quarterly (53): 422-459. • F. Murray and S. O'Mahony (2007). "Exploring the Foundations of Cumulative Innovation: Implications for Organization Science." Organization Science, Vol. 18, pp. 1006-1021. • F. Murray and L. Graham (2007). "Buying Science & Selling Science: Gender Stratification in Commercial Science". Industrial and Corporate Change Special Issue on Technology Transfer, Vol. 16:4, pp. 657-689. • W. Ding, F. Murray and T. Stuart (2006). "Gender Differences in Patenting in the Academic Life Scientists." Science , Vol. 313, pp. 665-667. Additional resources Black, L.J. and D.R. Greer, 2009, "You Meant What?! Socially Constructing Shared Meaning," working paper Boyd, J. 1992. "A Discourse on Winning and Losing" Note: Boyd did not appear to publish his research; documentation of some briefings may be found in Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, published in 2002 by Back Bay Books Carlile, P.R. “A Pragmatic View of Knowledge and Boundaries: Boundary Objects in New Product Development,” Organization Science,13, 2002. Henderson, K., “Flexible Sketches and Inflexible Data Bases: Visual Communication, Conscription Devices, and Boundary Objects in Design Engineering,” Science, Technology & Human Values,16, 1991 Lave, Jean, Cognition in Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988 Star, S.L. and J.R. Griesemer, “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39,” Social Studies of Science, 19, 1989. 75 Thank you!