Gerontology Program Review Self Study Contents Year 2008-2009

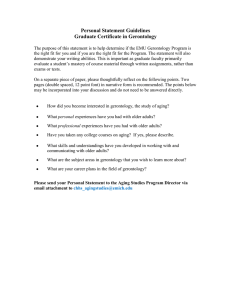

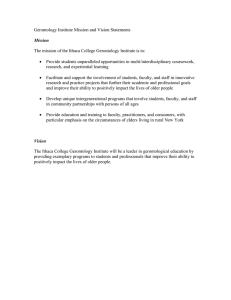

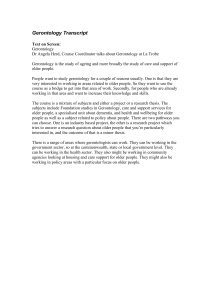

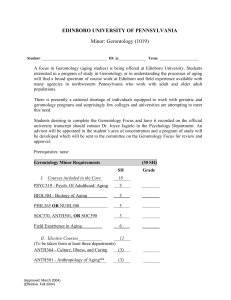

advertisement