CAN A MEDICAL SPECIALTY CAMP BECOME A VENUE OF PROVIDING

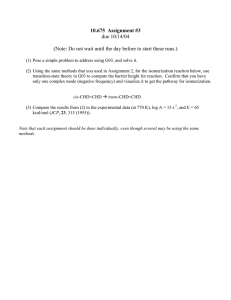

advertisement