ACCT323, Ch. 19, Webapp to

advertisement

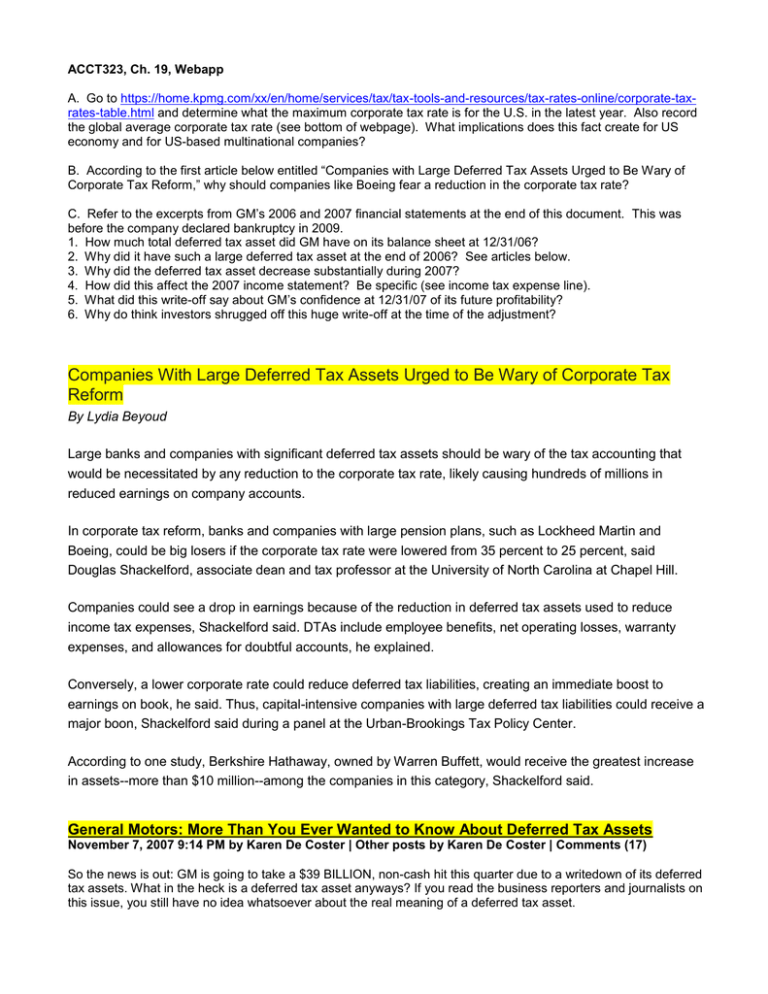

ACCT323, Ch. 19, Webapp A. Go to https://home.kpmg.com/xx/en/home/services/tax/tax-tools-and-resources/tax-rates-online/corporate-taxrates-table.html and determine what the maximum corporate tax rate is for the U.S. in the latest year. Also record the global average corporate tax rate (see bottom of webpage). What implications does this fact create for US economy and for US-based multinational companies? B. According to the first article below entitled “Companies with Large Deferred Tax Assets Urged to Be Wary of Corporate Tax Reform,” why should companies like Boeing fear a reduction in the corporate tax rate? C. Refer to the excerpts from GM’s 2006 and 2007 financial statements at the end of this document. This was before the company declared bankruptcy in 2009. 1. How much total deferred tax asset did GM have on its balance sheet at 12/31/06? 2. Why did it have such a large deferred tax asset at the end of 2006? See articles below. 3. Why did the deferred tax asset decrease substantially during 2007? 4. How did this affect the 2007 income statement? Be specific (see income tax expense line). 5. What did this write-off say about GM’s confidence at 12/31/07 of its future profitability? 6. Why do think investors shrugged off this huge write-off at the time of the adjustment? Companies With Large Deferred Tax Assets Urged to Be Wary of Corporate Tax Reform By Lydia Beyoud Large banks and companies with significant deferred tax assets should be wary of the tax accounting that would be necessitated by any reduction to the corporate tax rate, likely causing hundreds of millions in reduced earnings on company accounts. In corporate tax reform, banks and companies with large pension plans, such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing, could be big losers if the corporate tax rate were lowered from 35 percent to 25 percent, said Douglas Shackelford, associate dean and tax professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Companies could see a drop in earnings because of the reduction in deferred tax assets used to reduce income tax expenses, Shackelford said. DTAs include employee benefits, net operating losses, warranty expenses, and allowances for doubtful accounts, he explained. Conversely, a lower corporate rate could reduce deferred tax liabilities, creating an immediate boost to earnings on book, he said. Thus, capital-intensive companies with large deferred tax liabilities could receive a major boon, Shackelford said during a panel at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. According to one study, Berkshire Hathaway, owned by Warren Buffett, would receive the greatest increase in assets--more than $10 million--among the companies in this category, Shackelford said. General Motors: More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Deferred Tax Assets November 7, 2007 9:14 PM by Karen De Coster | Other posts by Karen De Coster | Comments (17) So the news is out: GM is going to take a $39 BILLION, non-cash hit this quarter due to a writedown of its deferred tax assets. What in the heck is a deferred tax asset anyways? If you read the business reporters and journalists on this issue, you still have no idea whatsoever about the real meaning of a deferred tax asset. Without getting too complicated, think about it this way: a corporation has a set of accounting books, or rather, its "general ledger." That corporation also has its tax returns, and accordingly, books and tax are not running on the same set of rules. Books are governed by GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) and taxes are lorded over by the Internal Revenue Code. The criteria for recognizing income and expense items for book purposes are not the same criteria that apply to tax law. Thus taxable income - for tax purposes - is not the same as financial accounting income for book purposes. So when taxable income and book income don't match, a future tax consequence is created. This can be a tax asset or a tax liability. Some transactions give rise to permanent differences between the books and tax (for example, something that is deductible for book purposes but not for tax purposes). A permanent difference will impact either the books *or* tax, but not both, so it does not create a "temporary" difference. Thus it does not give rise to a tax asset or liability. In the case of a deferred tax asset, a "deductible temporary difference" is created. A deferred asset means a transaction took place which will result in a decrease in taxable income in future years. Thus taxes will be "saved" in future years, giving rise to this "asset." A company may have instances wherein it wrote down assets on its books, however, expenses are not recognized for tax purposes because it is not a "cash event." The company could expect tax savings in the future. If that company wrote down $1 billion of assets and its tax rate is 38.9%, then it has created a future tax effect of $389,000,000 - a tax asset. The corporation, then, can estimate the value of its future savings, or deferred tax asset, and this is carried on the balance sheet. I don't yet know enough about GM's specifics and would rather not speculate. The problem here is that GM is so unprofitable that its bean counters realized that they had to come clean and write down the value of its future tax assets because it has become completely unpredictable as to when the company can actually return to making a profit, and thus use that tax asset against any future tax liability it incurs. Essentially, GM is admitting defeat and is not confident about making profits anytime soon. Hence the write-off. This is a huge indicator of management's pessimism about the coming years. GM's last balance sheet (June 30, 2007) shows a negative equity position of $3.5 billion. Considering the write-off, the September 30, 2007, 3rd-quarter balance sheet will tell a disastrous story. Likely, the next buzzword that journalists will swoon over will be "going concern." In financial accounting, "going concern" means that the company's value, as reflected by its balance sheet, must reflect the value of the company in the long-term (beyond one year). A company facing certain bankruptcy, as reflected in its balance sheet, is not a going concern. Accountants and auditors must act on the principles of going concern when preparing or auditing financial statements. GM, in writing down its tax assets as it did, made a negative judgment about the uncertainty of future events and their outcome. In 2001, when 257 publicly-traded companies went bankrupt, only 48% of these companies had audit reports that included the auditor's explanatory paragraph expressing doubts about the company being a "going concern." A huge, huge failure for the audit-accounting industry as a whole. Lastly, I have long been writing about General Motors and the fact that it operates on the verge of insolvency. I have been vilified for doing so. However, the trend for GM has been the build-up of negative equity, negative working capital, insurmountable losses, and previously, its only profits were coming from its finance arm until it sold majority stake in GMAC. More on its balance sheet woes to come soon. GM — Holy negative accounting equity, Batman! Apparently GM is going to take a $39 billion dollar write-down of deferred tax assets this quarter. Wow. The phrase "deferred tax assets" is one of many powerful hexes the accounting profession has invented over the years. Recitation of the words before ordinary mortals causes eyes to glaze and specks of spittle to appear at corners of the mouth. For an explanation, see the end of this post. Anyway, as all the overnight press on the matter is careful to emphasize, these are non-cash charges, and they could be reversed if GM becomes profitable soon. Nothing to look at here, just move along. It's an accounting thing, you wouldn't understand. But here's an accounting thing for you. Check out GM's top-level balance sheet last quarter (the quarter ending Jun-07). Look at the line called "Total stockholder equity". Yes, it really does say negative 3.5 billion dollars. Suppose GM offsets the write-down of tax assets with $9B of gains elsewhere, so that the net charge is, um, only $30B. (For example, they're expected to report a gain of $5B on their sale of Allison Transmission.) A $30B net charge would bring GM's accounting equity down to negative 33 billion dollars. Is that a record? What's the maximum negative accounting equity ever reported by a going concern? Or, consider this: GM is not a penny stock. The market imputes a lot of real value to those claims worth negative dollars on its balance sheet. GM's market cap as of yesterday was about $20.5B. That's a positive number. GM's stock price fell after-hours on announcement of the charge by about 3%. So, incorporating (at least partially) the new information, the market imputes about positive $19.9B of value to roughly negative 30 billion dollars worth of book assets. There's a nice fifty-billion dollar spread between market and book value. If GM could keep that spread, but bring its book value up to positive a billion, it would look like an incredible growth company, with a market to book ratio of 50 times! Google looks cheap by comparison. Now, there are serious problems with accounting equity as a measure of value. GM is an old company. Perhaps it owns a lot of real assets that were purchased decades ago and are still valued on its books at 1940s cost. Could be. But it takes a lot of adjustments to get out of a hole $30B deep. An interesting factoid from the WSJ. GM's total net income for 1996 through 2004 totaled $34 billion dollars, less than is disappearing in tomorrow's accounting "poof". Here's a question: What percentage of GM's market valuation do you think is based on a market-perceived "too big to fail" guarantee by the US government? -------------------------------------------------------------------------------For those who want to know, "deferred tax assets" arise when firms recognize expenses before they are allowed to take a tax deduction for those expenses. Let's say a large New York bank decides some of its assets are worth 10B less than originally thought, and writes those assets down on its balance sheet. If the bank pays a 35% tax rate, 3.5B of that "loss" should eventually be absorbed by the government in the form of reduced tax payments. But companies don't get to pay fewer taxes whenever they change their estimate of the value of an asset. The bank gets a cash write-off on its taxes only when the assets are actually sold and the firm realizes a loss. In the meantime, the firm recognizes a 3.5B "tax asset", the value of the future tax savings it expects. This is all perfectly legitimate — writing down the assets without recognizing the expected tax-savings would badly overstate costs. But sometimes a firm's estimate of future tax savings turns out to be wrong. Say the bank is forced to sell the impaired assets when it is already losing money. Then there is no immediate tax savings, because the bank wouldn't have paid taxes that year anyway. The firm may still be able to "carryforward" the loss, and recover some of the tax savings. Or it may not. Tax laws are complicated. GM had previously estimated that it had $39B in future tax write-offs coming to it. Its accountants now think the company might never get the chance to use them. Though this is not a cash charge, it is not a good omen either. Firms realize tax assets when they are profitable enough to have a large tax bill to take deductions from. GM is basically announcing that it's unsure it will earn enough money to be able to take advantage of its pent-up tax offsets before they expire. Tax asset write-downs are insult-to-injury kind of events. Firms get hit with the accounting charge when, and precisely because, they can't make enough money to have a tax liability to escape from. Tax asset write-downs might also be a signal of distress, indicating that a firm lacks the flexibility to time its loss realizations advantageously. Tax laws are complicated, and sometimes tax benefits expire regardless of what a firm does. One mustn't draw conclusions. Still, it does make you wonder. GENERAL MOTERS INCOME STATEMENT AND BALANCE SHEET