midterm will be returned on Tuesday one point about efficiency

advertisement

Econ 522 – Lecture 13 (March 5 2009)

midterm will be returned on Tuesday

one point about efficiency

Last week, we looked at a number of formation defenses and performance excuses

incompetence

dire constraints

impossibility

fraud, failure to disclose, frustration of purpose, mutual mistake

contracts of adhesion and unconscionability

For impossibility and frustration of purpose, we came up with a simple rule for

achieving efficiency:

When changed circumstances make performance impossible or pointless, assign

liability to the party who can bear the risk at the least cost

We saw the rule that efficiency generally requires uniting knowledge and control

Which explains why mutual mistake will generally void a contract, but

unilateral mistake will not

We distinguished between productive information and redistributive information

And saw the principle of rewarding productive information – especially if it was

the result of active investment – to give an incentive to discover it

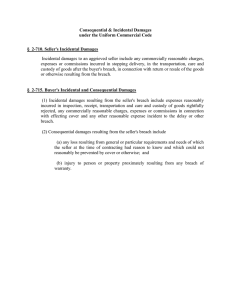

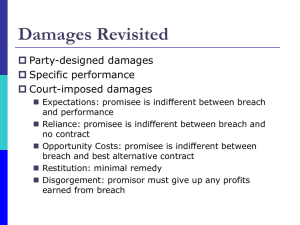

Next, we returned to the question of remedies. We defined several different remedies:

expectation damages, which restore the promisee to the level of well-being he

would have had if the contract had been performed

opportunity cost damages, which restore the promisee to the level of well-being

he would have had if he had pursued his next-best option instead of signing this

contract

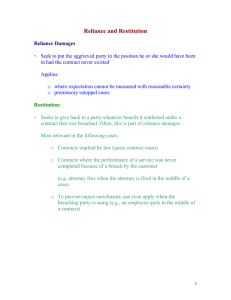

reliance damages, which reimburse the promisee for any reliance investments he

made

specific performance, which demands the promisor fulfill his promise rather than

order monetary damages

and we noted the possibility of party-imposed remedies – remedies which are

specified in the contract itself

-1-

However, common law courts are sometimes hesitant to enforce remedies that are

specified in the contract

One type of remedy that courts will often refuse to enforce is penalty damages

Penalty damages are damages that are greater than the actual harm that occurred

(“Liquidated damages” refer to party-specified damages that are a reasonable

estimate of the actual harm done by the breach; penalty damages are any damages

that are greater than that)

Civil law courts generally enforce penalty damages

But common law courts often set aside penalty damages, and only enforce liquidated

damages

It’s unfortunate that penalty clauses are often not enforced, because they could be

useful in some instances

In particular, they could be helpful when one party to a contract places a high

subjective value on performance

Go back to coal mining example we saw earlier, Peevyhouse v Garland Coal

The Peevyhouses only wanted their farm strip-mined if the land could be restored

to its original condition

They seemed to value the condition of their farm much more highly than “market

value”

Had they known the coal company would refuse to perform the restoration work,

and instead only pay them damages, they might have refused to agree to the

contract in the first place

We can illustrate this with a simple dynamic game

Suppose the coal extracted was worth $70,000 (net of costs), and Garland Coal

agreed to pay $25,000 to mine it

Recall that restoration work would have cost around $30,000, but damages for

refusing to do it were assessed at $300

Suppose that the Peevyhouses’ subjective valuation of their farm dropped by

$40,000

PEEVYHOUSES

Don’t

Sign

GARLAND COAL

Restore property

(25,000, 15,000)

Don’t, pay damages

(-14,700, 44,700)

-2-

(0, 0)

So the Peevyhouses anticipate that once the coal has been mined, Garland will

refuse to do the restoration work

So now the Peevyhouses refuse the original contract

One way to address this in a contract would have been to write into the contract a

$40,000 penalty in the event that the restorative work was not completed

If this was enforceable, it would ensure that the mining company followed

through with the restorative work

That is, it would change the game to this:

PEEVYHOUSES

Don’t

Sign

GARLAND COAL

Restore property

(25,000, 15,000)

Don’t, pay penalty

(0, 0)

(25,000, 5,000)

Now, the Peevyhouses are assured of getting their land restored

So they’re happy to agree to the contract

But, if common law courts don’t uphold penalty clauses, this won’t work

Another example: suppose you’re hiring a contractor to build a house, and you place a

very high value on its being completed by a particular date

You are happy to pay $200,000 to get the house built, but insist on a $50,000

penalty if it’s not ready on that date

Now suppose there are lots of contractors who could potentially build the house

If you offer this deal to lots of them, the ones who accept are likely the ones who

are most confident in their ability to finish the house on time

Since you value this highly, this may be efficient

And this may be the easiest (or the only) way for you to elicit this information

o If there is no penalty clause, every contractor will try to convince you he’s

100% certain he’ll finish on time

o But if someone accepts the $50,000 penalty clause, they’re probably pretty

sure

-3-

Of course, it’s also easy to come up with examples where penalty clauses seem excessive

and nasty

Imagine if Blockbuster charged late fees of $1,000 per day

You go to rent a video, they tell you it’s yours for a week, but it’s $1,000 if it’s a

day late

You might rent the video anyway, thinking it’s within your power to return it on

time

But in the event that something happens (your daughter gets sick, or you get

called out of town on business), you’re going to be pretty upset to be charged

$1,000

Similarly, a rental car company that attached a $50,000 fine to any damage to

their $10,000 car would look pretty mean-spirited

Still, in some instances, penalty damages seem beneficial

Especially if one party would not agree to a mutually beneficial contract without

them

So it seems like the fact that they’re not enforced is a problem

However, it turns out, most things you could accomplish with penalties, you could

restate in a different way with a performance bonus

Go back to the house-building example

o I’m happy to pay $200,000 to get the house built by a certain date

o But I insist on a $50,000 penalty if it’s not ready on time

We could alternatively write the contract this way:

o I pay $150,000 for the building of the house

o And I pay an additional $50,000 performance bonus if the house is

completed by a certain date

Courts generally have no problem enforcing contracts with bonuses in them, so

this would likely be enforced as written

But it ahs the same effect as the contract with the penalty

(Under either contract, the builder gets $200,000 for finishing the house on time,

and $150,000 for finishing it late.)

-4-

Similarly, go back to the Peevyhouse example

Instead of a $40,000 penalty that might not be upheld, the Peevyhouse contract

also could have been rewritten as a bonus

We imagined that Garland paid $25,000 to mine the coal

Suppose the contract were written in this way:

o Garland pays the Peevyhouses $65,000 to mine the coal

o The Peevyhouses pay Garland a $40,000 bonus if the resoration work is

completed

This would create exactly the same incentives as a $40,000 penalty clause

(In this case, though, the intent of the contract might have been so transparent that

it still might not have been enforced)

So that’s penalty damages.

-5-

Next, I want to consider the effect of different remedies for breach, in terms of the

incentives they lead to for…

the promisor’s decision to perform or breach

the promisor’s investment in performing, and

the promisee’s investment in reliance

Put aside the question of reliance for the moment, and suppose that performance

of the promise will have a fixed benefit for the promisee

The fact that the two parties agreed to the contract in the first place implies they

believed this benefit was likely to greater than the cost to the promisor of

performing

But as we’ve already discussed, circumstances may change after the promise is

made, in a way that makes the promisor less keen to keep his promise

o The price of building the airplane may go up

o My rich cousin may appear and value my painting more highly than you

There are two ways for me to get out of my promise

o I can renegotiate with you, getting you to “let me off the hook,”

presumably in exchange for some money

o Or I can breach our contract and live with the consequences, most likely

the damages that a court imposes

Think back to nuisance law, and consider some entitlement – say, the right to

breath clean air

When it was protected by injunction, the parties could still bargain for it – the

polluter could offer the neighbor enough money to be willing to live with the

pollution

When an entitlement was protected by damages, the polluter could instead simply

pollute and pay whatever damages were ordered

We found that when transaction costs were low, either remedy would lead to

efficiency

But since the two remedies changed the noncooperative outcome (the threat point)

for each side, they led to different allocations of surplus

On the other hand, when transaction costs were high, the two remedies could

lead to different results.

With contract law, the result is exactly the same

When transaction costs are low, all remedies lead to efficiency, but they will lead

to different outcomes for each party

When transaction costs are high, some remedies will be more efficient than others

-6-

For example, let’s compare a contract enforced by specific performance – the promisor

is not allowed to breach unless the promisee agrees – versus a promise enforced by

expectation damages

Let’s stick with the example of the airplane I agreed to build for you

The plane will give you a value of $500,000

We agree on a price of $350,000

I expect the plane to cost me $250,000 to build, but there is some chance it will

instead cost me $1,000,000

First, let’s consider what happens if our contract is protected by expectation damages.

I Get

You Get

Total

Costs Low

(Perform)

100,000

150,000

250,000

Costs High

(Perform)

-650,000

150,000

-500,000

Costs High (Breach,

pay exp damages)

-150,000

150,000

0

Now let’s see what happens if our contract is protected by specific performance, that is,

you have the right to demand the airplane, and I can only breach with your permission.

I Get

You Get

Total

Costs Low

(Perform)

100,000

150,000

250,000

Costs High

(Perform)

-650,000

150,000

-500,000

Costs High

(renegotiate)

0

Since performance is very costly, my threat point is very low, so renegotiation

may force me to accept fairly bad terms

Notice that by renegotiating the contract, we create a total surplus of $500,000

(beyond our outside options if you forced me to build the plane)

Suppose that our negotiations lead us to divide this additional surplus evenly

This would lead you to get $250,000 beyond your outside option, which was

$150,000, so your payoff would be $400,000

I would get $250,000 beyond my outside option, which was -650,000, which

would be -400,000

(So this means, in return for getting out of the contract, I pay you $400,000)

-7-

As long as transaction costs are low, either remedy will lead to the same outcome

o When it is efficient to breach, expectation damages lead me to breach

without permission

o Under specific performance, when it is efficient to breach, renegotiation

will lead us to some sort of agreement to let me off the hook.

But when the transaction costs of renegotiating our contract are too high…

o Expectation damages still allow me to breach

o Specific performance would lead to inefficient performance

o I would have to build you the plane, even though it costs me more than

your benefit

Other types of damages – opportunity cost damages, or reliance damages – would

lead to inefficient breach

That is, I would choose to breach even when my cost of performing is lower than

your benefit

However, when transaction costs are low, this could also be fixed through

renegotiation.

For example, consider opportunity cost damages

Suppose that the next-best contract would have sold you a similar plane for

$400,000, but that now at this late date, no other planes are available

We agreed on a price of $350,000, but now costs go up somewhat, to $460,000.

Perform

I Get

You Get

Total

-110,000

150,000

40,000

Breach and pay Opp

Cost Damages

-100,000

100,000

0

Renegotiate and

Perform

P – 460,000

500,000 – P

40,000

Renegotiating the contract (instead of me breaching) generates additional surplus

of $40,000

If we split this evenly, we would each get a payoff $20,000 higher than our

outside option, which would require the renegotiated price to be $380,000

Again, however, if transaction costs were high, we would be unable to renegotiate

the contract, and I would choose to breach and pay you $100,000 in opportunity

cost damages.

(Cooter and Ulen point out that, just like efficiency demands enforcing contracts

whenever the parties wanted them to be enforceable, efficiency demands enforcing

renegotiated contracts whenever the parties wanted them to be enforceable at the time of

renegotiation.)

-8-

So just like with nuisance law, we find the following:

if it is cheap/easy to renegotiate terms, any of the remedies will lead to efficient

breach, although they will lead to different allocations of surplus

if it is expensive/hard to renegotiate terms, only expectation damages are

guaranteed to lead to efficient breach – specific performance may lead to

inefficient performance, and lower damages may lead to inefficient breach

An increase in the cost of performance is referred to as an unfortunate

contingency

On the other hand, I may want to break my promise because I discover another

buyer who values my product more than you do

This is referred to as a fortunate contingency

Earlier, we saw the example where you contracted to buy my painting, but my

rich cousin appeared and valued it much more highly than you did

We can do the same exercise as before with the different remedies, and see the

same thing

o With low transaction costs, any remedy will lead to efficient breach, but

with different allocations of surplus

o An example of this is done in the textbook (p. 267)

o Once again, specific performance is the most advantageous to the buyer,

and higher damages are better for the buyer than lower damages.

-9-

<<< SKIPPED THIS PART IN LECTURE >>>

One further point that we mentioned earlier but didn’t talk much about: efficient signing.

We saw that with expectation damages, when my costs remain low and I perform,

I get a profit of $100,000 (the price you pay, $350, minus the costs I incur, $250)

And when my costs jump up and I breach, I owe $150,000

If the probability my costs rise is small enough, that’s no big deal

I take the risk of owing you expectation damages, because my profits in the cases

where I don’t breach are large enough that it’s worth the risk.

But if the probability my costs rise is high, then my expected profit from this

contract is negative

For example, suppose the probability of a dramatic rise in costs is ½

Then my expected payoffs from agreeing to build you the airplane are

½ (100,000) + ½ (-150,000) = -25,000

So now there’s no way I’d agree to the contract in the first place

This is the point we mentioned before:

Expectation damages lead to efficient breach, but they may lead to inefficient

signing

(If I’m the only airplane manufacturer available, it’s still efficient for us to sign

this contract – it generates positive expected surplus – but under expectation

damages, I would not sign this contract.)

This suggests that, even if expectation damages make a sensible default rule, it’s

efficient for parties to be able to specify a different damages rule in the contract

That is, even if expectation damages are often efficient, they are not always

efficient, so there’s no reason for them to be mandatory

<<< END SKIP >>>

- 10 -

So that’s breach

What’s left is investment in reliance, which we’ve already talked a bit about; and

investment in performance, which we haven’t.

The book makes a big deal out of “the paradox of compensation”

This is an idea we’ve already mentioned: the remedy for breach sets an incentive

for both the promisor and the promisee, and it’s generally impossible to set both

of these incentives efficiently at the same time

(The particular conflict they look at here is the way that reliance figures into

expectation damages.)

Let’s go back to the airplane example once again, and again assume that, once

you contract to buy my plane, you consider building yourself a hangar

But this time, rather than just a decision to build or not build, there is a whole

range of different-quality hangars you could elect to build.

Suppose that, for any investment of x dollars, you can build a hangar that will enhance

the value of having a plane by 600 sqrt(x), but is worthless without a plane.

Investment

x

100

Value of

Hangar

600 sqrt(x)

6,000

10,000

40,000

160,000

640,000

60,000

120,000

240,000

480,000

Large tarp held up by some rope connected to a telephone

pole – still keeps some rain off the airplane

Basic plywood frame, canvas roof

Metal poles, rigid roof

Functional heating

Designer hangar with working Starbucks

Recall that whatever investment is made in reliance pays off when the promise is kept,

but is lost when the promise is broken.

- 11 -

We will ask three questions:

1. What is the efficient level of reliance?

2. What would the buyer do if expectation damages included the anticipated benefit

from reliance?

3. What would the buyer do if expectation damages do not include the anticipated

benefit from reliance?

First, What is the efficient level of reliance?

The total social gain from the contract when costs stay low is

500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 250,000 – x

The total social gain is from the contract when costs go up and the seller breaches

is –x (the reliance investment is lost, everything else is just transfers)

Suppose the probability of breach is p; then the expected social benefit is

(1-p) (500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 250,000 – x) + p(–x)

We can simplify this to

250,000*(1 – p) + 600 (1– p) sqrt(x) – x

If we take the derivative and set it equal to 0, we get

600 (1 – p) / 2sqrt(x) – 1 = 0

If we solve this for x, we find the efficient level of reliance is 90,000 (1-p)^2

- 12 -

Next, what will the buyer do if that expectations damages include the benefits

anticipated based on reliance investments?

Then the buyer knows he’ll get the added benefit, whether or not the seller

performs

So in deciding how nice a hangar to build, the buyer would maximize

500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 350,000 – x

Solving this gives the first-order condition

600/2sqrt(x) – 1 = 0 x = 300^2 = 90,000

So the buyer, when insulated from the risk of breach, invests $90,000 in a pretty

nice hangar, which gives anticipated benefit of 600 sqrt(90,000) = 180,000

Note that the reliance investment, 90,000, is more than the efficient level,

90,000(1-p)^2, as long as p > 0 (there is any chance of breach)

This makes sense: in this scenario, reliance imposes a negative externality on the

seller (since he incurs a greater cost when he breaches), so it is overprovided

Or, the buyer gets all the benefit from reliance, but not all of the cost, so he

invests too much

On the other hand, suppose expectation damages do not include the benefits of reliance

Then the buyer maximizes

(1-p) (payoff without breach) + p (payoff with breach)

= (1-p) (500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 350,000 – x) + p (150,000 – x)

= 150,000 + (1-p) 600 sqrt(x) – x

This leads to the efficient level of reliance

So if damages include the gains from reliance, this leads to overreliance

But if the level of damages excludes the gains from reliance, this leads to efficient

reliance

But we also know that if the level of damages exclude the gains from reliance,

and the buyer relies anyway, that this will lead to inefficient breach

That is, since the seller’s liability from breach is lower than the buyer’s gain from

performance, there will be some instances where the seller breaches even though

efficiency requires performance

- 13 -

We said before that with no transaction costs, this problem can be solved

o When breach would be inefficient, the parties can contract around it

o Since it’s generally very clear whether a party has breached a contract or

not, this shouldn’t be a particular problem.

However, there are situations in which a promisor can take actions to make

performance less costly

Or, to put it another way, to lessen the probability that breach is necessary

o A contractor could buy raw materials ahead of time, to avoid the risk of

changing prices

o A manufacturer could start a project earlier and frontload the labor to

avoid the risk of a strike

o If a project were to require a building permit or zoning easement, he could

lobby the local government (or bribe someone) to decrease the chances of

hitting a snag.

This sort of investment in performance, however, may be unobservable, or

unverifiable

So even when this sort of investment is efficient, it may be very hard to build it

into the contract

(It’s very hard to enforce a contract specifying “how hard I have to try” to

convince the zoning board to approve your project.)

So investment in performance may only occur when it is in the promisor’s best

interest

We’ll stick with the airplane example

Suppose there is some investment I can take that reduces the chance that my costs

go up

o I can buy some of my supplies ahead of time

o This will reduce the risk of having to breach

o But I can’t completely insulate myself from risk

Suppose that for each $27,726 I invest, I can reduce the probability I will need to

breach by ½

o That is, if I invest $27,726, the probability of breach goes from ½ to ¼

o If I invest another $27,726, it goes down to 1/8

o And so on

For any investment z, then, we can write the probability that breach is still

required as ½ * ½ ^(z / 27,726)

- 14 -

The reason I chose the number 27,726 is that we can rewrite this probability as

½ e^{- z/40,000)

which makes it much easier to work with.

So, how much will a self-interested promisor invest in performance?

Let’s let D be the amount of damages that the promisor is liable for if he breaches

o D could be nothing

o or the investment in reliance

o or the opportunity cost

o or the gain the buyer expected to achieve, with or without reliance.

But suppose that D is low enough that the seller will still choose to breach when

costs go up

o Since we’ve been talking about costs rising to 1,000,000, this just requires

D < 650,000, the loss I would take from performing

When costs remain low, the seller expects $100,000 in profits

So when deciding how much to invest in performance, the seller maximizes

(1 – Pr(breach)) 100,000 + Pr(breach) (-D) – investment in performance

= 100,000 – Pr(breach)(D + 100,000) – z

= 100,000 – ½ e^(-z/40,000) (D+100,000) – z

Taking the derivative gives

½ 1/40,000 e^(-z/40,000) (D+100,000) – 1 = 0

½ e^(-z/40,000) = 40,000/(D+100,000)

So whatever D is, the seller invests enough to reduce the probability of breach to

40,000/(D+100,000)

If the seller can breach for free, he’ll invest enough to reduce the probability of

breach from ½ to 40,000/100,000 = 2/5

o He still prefers profits (100,000) over nothing

o But he only invests a little, since he can still get out of the contract for free

o (The investment here is about $9,000.)

- 15 -

Suppose D was expectation damages, without reliance

If he would owe expectation damages (without reliance) of $150,000, then he

invests enough to reduce the chance of breach from ½ to

40,000/(150,000+100,000) = 4/25 = 16%

(The investment this time is about $45,000.)

Suppose D was expectations damages, with reliance

We said that if expectation damages include reliance, the buyer spends $90,000

on a hangar giving $180,000 in benefits

So the promisee’s benefit from performance is now 500,000 – 350,000 + 180,000

= 330,000

With damages at that level, the seller invests enough to reduce the probability of

breach to 40,000/(330,000 + 100,000) = 40/430 = 9%

(The investment to do this is about $67,000.)

But what would be efficient?

Suppose that the buyer has already decided to build himself that nice $90,000

hangar

So the benefit of performance is 330,000

The cost of the hangar is sunk, so we can forget about it for now

The total social surplus is

(1 – Pr(breach)) (330,000 + 100,000) + Pr(breach) (0) – z

= 430,000 – 430,000 ½ e^(-z/40000) – z

To maximize this, we take the derivative:

430,000 ½ 1/40,000 e^(-z/40000) – 1 = 0

Pr(breach) = 40,000/430,000

So given that level of reliance, the efficient level of investment in performance is

enough to reduce the chance of breach to 40,000/430,000

Which we just saw is exactly what the seller would do when he’s liable for

expectation damages which include the benefit from reliance!

- 16 -

So we’ve found…

The efficient level of investment leads to a 40,000/430,000 chance of breach

Damages which are set equal to D lead to a self-interested promisor to allow a

probability of breach of 40,000/(D + 100,000)

So when damages are set to 330,000 – damages include the benefit from reliance

– the investment in performance is efficient

When damages are lower than that, the seller will underinvest in performance,

leaving the risk of breach inefficiently high

When damages are higher than this, the seller will overinvest in performance

And what’s the overall lesson?

Making the seller liable for reliance – that is, increasing expectation damages to

include benefit due to reliance – leads the seller to invest efficiently in

performance; just like it led to efficient breach

But it leads the buyer to overinvest in reliance

On the other hand, making the seller not liable for reliance – leaving

expectation damages where they were without reliance – leads to

underinvestment in performance

But it leads to the efficient level of reliance

So like we saw last week with the sailboat example from Friedman:

The level of damages leads to multiple different incentives

And it’s impossible to come up with a level of damages that makes everyone

behave efficiently

We already saw one attempt to get around this problem:

limit damages to the efficient level of reliance, not the actual level of reliance

that way, the promisee has no incentive to overinvest in reliance, so he invests the

efficient amount

but the promisor still internalizes the full cost of breach

so he invests the efficient amount in performance

The textbook also discusses another clever, if unrealistic, solution to the problem, which

is where we’ll begin on Tuesday.

- 17 -