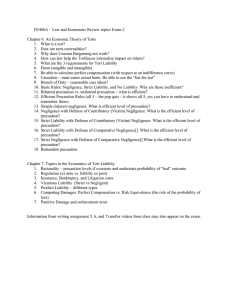

Econ 522 – Lecture 16 (Nov 6 2008)

advertisement

Econ 522 – Lecture 16 (Nov 6 2008) Tuesday, we began tort law Defined the three elements of a tort under the traditional theory – harm, causation, and breach of duty (not always required) Defined a strict liability rule as one which assigns liability based only on harm and causation, and a negligence rule as one which requires all three elements That is, under strict liability, you’re responsible for any damage you do; under negligence, you’re responsible for any damage you do if you were being careless (if you breached the duty of due care) We introduced a simple model of unilateral precaution, where one party (maybe the injurer, maybe the victim) chooses ahead of time how much precaution to take, where the more precaution is taken, the lower the likelihood of an accident Letting x denote the level of precaution, p(x) the probability of an accident, A the cost of an accident, w the marginal cost of precaution: wx p(x) A precaution We said efficiency requires minimizing total social cost, which is wx + p(x) A o add it to the graph We said that when there is no liability, the victim bears the full cost of accidents o This leads to efficient levels of precaution when it’s victim precaution o But inefficiently low precaution when it’s injurer precaution In contrast, when there is strict liability (with perfect compensation), the injurer internalizes the cost of his actions o Leads to efficient precaution when it’s injurer precaution o But now victim does not bear cost of accidents, so inefficiently low precaution when it’s victim precaution We can sum up the results so far: Legal Rule Victim’s Precaution No liability Efficient Strict liability Zero Injurer’s Precaution Zero Efficient So like with the paradox of compensation in contract law, we haven’t yet found a single rule that sets incentives correctly for every situation. But in tort law, there is a trick We defined a negligence rule, under which the injurer is liable for harm only if he did not take certain precautions o We can make damages depend not only on whether an accident occurred, but also on the actions that led up to it o This may allow us to get both incentives right. Case 3: Negligence Rule A negligence rule says that the injurer is liable for damages if his precaution level was below the legal standard of care, x~. So for x < x~, damages would be D = A; for x >= x~, damages would be D = 0. If we go back to the graphs we drew earlier, then, the total expected cost to the injurer (from both precaution and expected damages) will be wx + p(x) A for x < x~, and just wx for x >= x~, since when x >= x~, the injurer is not liable for damages. How this actually looks will depend on how x~, the legal standard for precaution, relates to x*, the efficient level of precaution. For now, let’s assume they’re equal, that is, x~ = x*. The dark-shaded curve is the injurer’s expected private costs under a liability rule, when x~ = x*: wx + p(x) A wx x~ = x* precaution At x < x*, we know that wx + p(x)A is decreasing; and so the injurer’s expected costs are decreasing. Similarly, we know that wx is increasing, so above x*, the injurer’s expected costs, which are just wx, are increasing. So expected costs are minimized by setting x = x*, the efficient level. So a negligence rule, with a legal standard of care x~ equal to the efficient level x*, leads to an efficient level of injurer precation. What about the victim’s incentives? The victim knows that under a negligence rule, the injurer will take precaution x*; and therefore, if an accident occurs, the injurer will not be liable. So now the victim is facing the full cost of any accident which occurs; which means that the victim also takes the efficient level of precaution. So now we’ve found a solution to the “paradox of compensation”: A negligence rule, combined with an efficient legal standard for care, leads to efficient precaution by both injurer and victim. Which is pretty cool. So we can add another row to our table of results from before: Legal Rule No liability Strict liability Negligence, x~ = x* Victim’s Precaution Efficient Zero Efficient Injurer’s Precaution Zero Efficient Efficient This works great for cases of unilateral precaution – when in each situation, only one party has a way to reduce the risk of accidents. It also works pretty well in cases of bilateral precaution. However, in cases of bilateral precaution, there are several different ways to implement a negligence rule. The one that we have seen so far is called simple negligence. Under a simple negligence rule, the injurer is liable if his level of precaution, xi, was below the legal standard, xi~; if it was above xi~, he is not liable. And that’s the whole story. (What the victim was doing doesn’t matter.) Under a different rule, however, a negligent injurer can escape liability if the victim was also being negligent. For example, if I’m driving carelessly (talking on my phone, changing CDs) and hit someone, I may be liable; but if I can show that the guy I hit was drunk, and stumbled into the street right in front of me, his negligence cancels out mine and I don’t owe him damages. This type of rule is called negligence with a defense of contributory negligence Under this rule, if the injurer took insufficient precautions, xi < xi~, and the victim took sufficient precautions, xv >= xv~, then the injurer is liable for damages However, if the injurer took sufficient care, xi >= xi~; OR the injurer was negligent, xi < xi~, but so was the victim, xv < xv~, then the injurer is not liable for damages. Like simple negligence, a rule of negligence with a defense of contributory negligence (with standards of care equal to their efficient levels) leads to efficient precaution by both parties. The injurer expects the victim to take the efficient precautions, xv = xv~; so he knows that if he takes insufficient care, xi < xi~, he’ll be liable, and if he takes sufficient care, xi >= xi~, he will not be; so he minimizes expected costs by setting xi = xi~ = xi*. The victim, on the other hand, expects the injurer to take efficient precautions, so he expects to receive no damages, whether or not he himself is negligent; so he sets the efficient level of care, xv = xv*. A third type of rule holds that if both parties are negligent and an accident occurs, then since they share the blame, they should share the responsibility. This is referred to as comparative negligence. If the injurer is not negligent, xi >= xi~, he owes no damages If the injurer is negligent, xi < xi~, and the victim is not, xv >= xv~, then the injurer bears the full cost of the accident But if both were negligent, xi < xi~ and xv < xv~, then they share the cost of the accident; damages are paid, but they are less than the full cost of the accident. (In theory, the damages are based on the relative contribution of each side’s negligence to the accident, or the relative amounts that each one is at fault.) Like the other two rules, comparative negligence (with efficient legal standards) also leads to both parties taking the efficient level of precaution. We’ve now considered three variations of a negligence rule: Simple negligence Negligence with a defense of contributory negligence Comparative negligence One other variation to consider is a rule of strict liability with a defense of contributory negligence. That is, regardless of his level of care xi, the injurer is liable for damages, unless the victim was negligent, in which case he is not. Formally, if xv >= xv~, the injurer is liable; if xv < xv~, the injurer is not. Cooter and Ulen point out that this rule is sometimes used with consumer products. A manufacturer of a defective product is often liable for damages, except when the consumer was negligent in how they used the product. (If a coke bottle explodes in my hand, Coca-Cola is liable; but if I left it in the sun and shook it, then not so much.) Once again, this type of rule (with appropriate standards) leads to efficient precaution by both parties. The logic is the same. The victim, knowing he will be liable if he is negligent, does best by choosing the legally required level of care, xv = xv~. So the injurer internalizes the full cost of any accidents, and therefore takes the efficient level of care, xi = xi*. So we have now seen the following: No liability leads to efficient care by the victim, but no care by the injurer Strict liability leads to no care by the victim, efficient care by the injurer Any of the four variations on a negligence rule (with legal standards equal to efficient levels of precaution) lead to efficient care by both parties (With basically any version of a negligence rule, one of the two parties can escape liability by meeting the legal standard for care. As long as that legal standard coincides with the efficient level, that leads one party to take efficient precaution. But this leaves the other party facing the entire social cost of the accident, and therefore leads that party to take the efficient level of precaution as well, for the purely selfish reason of minimizing expected private cost.) Our original table was for unilateral precaution – just one party can take actions that affect the likelihood of accidents. Negligence rules are better for cases of bilateral precaution – cases where some degree of care from both parties is efficient. There are also some instances where either party could take precaution, but efficiency only requires one of them to. (Picture two drivers on a dark road that both of them know well. Really only one of them needs to have his headlights on – it could be either one.) This is referred to as redundant precaution. In the case of continuous levels of precaution, everything still carries through. However, when precaution is discontinuous – such as your headlights being on or off – different negligence rules will not all lead to efficient precaution. Cooter and Ulen give the example that a driver can fasten his seat belt a lot more easily than a car company could design a seat belt that fastens automatically. Under a simple negligence rule, a driver who didn’t buckle his seat belt could sue the car company, so the car company might choose to incur the higher costs of the auto-buckle. Under a negligence rule with a defense of contributory negligence, the car company would not have to do this to escape liability, and a rational driver might choose to buckle up manually. As long as things are continuous, though, redundant precaution isn’t a problem. So far, we’ve come up with the following conclusions: Legal Rule No liability Strict liability “Any” negligence rule with efficient standards of care Victim’s Precaution Efficient Zero Efficient Injurer’s Precaution Zero Efficient Efficient However, there is another dimension in which peoples’ choices affect the likelihood of an accident: activity level. I can choose to drive carefully or recklessly, and I can also choose to drive more or less often. You can look both ways before crossing the street, or not; and you can choose how many streets to cross. First, let’s think about what happens under no liability. Under no liability, I’m never responsible if I hit you. So I don’t consider the cost of accidents when I decide how carefully to drive, or how much to drive; my precaution level will be too low (relative to the efficient level), and my activity level will be too high. What about you? You bear the costs of all accidents; so you look to maximize the benefit of walking, minus the cost of precaution (paranoia?), minus the expected cost of accidents. Your actions have no externalities (since only you get hurt by accidents, not me); so your incentives are correct, and you will set the efficient level of precaution and the efficient activity level. The exact opposite will happen under strict liability. Under strict liability, you know you will be compensated for any accidents, so you don’t worry about their costs. Therefore, you take insufficient precautions, and you set too high an activity level. On the other hand, I know I’m paying for any accidents that happen, so I consider their costs when I make my decisions; I take efficient precautions, and set an efficient activity level. What happens under a negligence rule? First, consider simple negligence. I know I won’t be liable as long as I take sufficient care; so under a simple negligence rule, I’ll take efficient precaution. But once I’m doing that, I don’t have to worry about the cost of accidents, since I’m not going to owe any damages; so I don’t consider the cost of accidents when I choose my activity level, and therefore I set it too high. Under a simple negligence rule, I’ll drive carefully, but I’ll still drive too much. As for you, you know I’ll be driving carefully, so you know that you’ll still be incurring the costs of any accidents that occur; so you set both your precaution level and your activity level efficiently. The same will be true for a rule of simple negligence with a defense of contributory negligence, or a rule of comparative negligence. We know that both these rules lead to efficient precaution; but as long as we’re both taking efficient precaution, I’m still not liable for damages. So you still bear the “residual risk” of accidents, and I don’t; so you set your activity level efficiently, and I set mine too high. Once again, under any of these rules, I drive carefully; but since I’m driving carefully, I know I won’t be liable for accidents, so I choose to drive too much. Finally, what happens under a strict liability rule with a defense of contributory negligence? Here, I’m liable for damages unless I can show you were negligent. We know that this will lead you to take efficient precaution; which means I expect to be held liable for any damages that occur. Thus, I internalize their cost, and set both my precaution level and my activity level efficiently. On the other hand, since you’re being careful, you know that you won’t bear the cost of accidents; so you ignore their cost, and set your activity level too high. Legal Rule No liability Strict liability Simple Neg Simple Neg, Contrib Neg Comparative Neg Strict Liab, Contrib Neg Victim Precaution Efficient Zero Efficient Efficient Injurer Precaution Zero Efficient Efficient Efficient Victim Activity Efficient Too High Efficient Efficient Injurer Activity Too High Efficient Too High Too High Efficient Efficient Efficient Too High Efficient Efficient Too High Efficient Which rule is the most efficient, then, depends on the situation. That is, it depends on whose choices have the bigger impact. In situations with unilateral precaution – situations where only one party needs to take steps to avoid accidents – no liability or strict liability work perfectly well. In situation with bilateral precaution, negligence rules give appropriate incentives for precaution on both sides. However, under any negligence rule, one of the two parties still bears whatever losses do occur – one party is the residual bearer of the harm of accidents, and the other party is not. Any negligence rule yields an efficient activity level by the residual risk bearer, but an inefficient activity level by the other party. Thus, the optimal rule depends on whose activity level is most important. The Shavell paper on the syllabus, “Strict Liability versus Negligence,” is all about these incentives. We’ll talk about it on Tuesday. It’s an excellent read. Friedman has a different take on activity levels. He argues that reducing your activity level is just another type of precaution; but it’s a type of precaution where it’s impossible for the court to determine the efficient level. (A court might be able to figure out that it’s efficient for me to drive with my headlights on at night, but unable to figure out how many miles it’s optimal for me to drive in a given day. Therefore, a court might find me negligent if I was driving without headlights; but it’s hard for a court to decide whether a particular trip was socially efficient, and therefore whether I was negligent by being in my car!) Instead of distinguishing precaution from activity levels, Friedman distinguishes observable precaution from unobservable precaution. He points out that any negligence rule only causes an efficient level of observable precaution, since that’s all that can be used to determine whether someone exercised due care or was negligent. So a negligence rule does not lead to an efficient level of unobservable precaution. Strict liability, on the other hand, leads the injurer to internalize the cost of accidents, so it leads to efficient levels of both observable and unobservable precaution – the same result as we already saw, just in different words. Friedman mentions that Posner uses this to explain why highly dangerous activities (blasting with dynamite, or keeping a lion as a pet) are often governed by strict liability; if they’re dangerous enough, the only meaningful type of precaution may be to not do them at all. Strict liability leads to efficient levels of both care (if you choose to do them) and a choice of whether or not to do them in the first place.