Econ 522 – Lecture 9 (Oct 2 2008) Homeworks?

advertisement

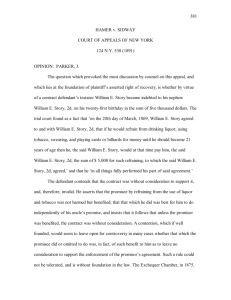

Econ 522 – Lecture 9 (Oct 2 2008) Homeworks? Our next big topic: contract law Fundamentally, contract law is the attempt to make certain types of promises legally binding Why do we want this? Suppose I have an opportunity to make a valuable investment, but I don’t have any money. You have some money, but don’t have access to the investment on your own. You could give me your money, I could invest it for you, and then we could split the proceeds: if you lent me $100, I could invest it, double our money, and promise to give you back $150 and keep $50 for myself. But there’s no way for you to be sure, once I’ve doubled your money, that I’ll choose to give you back your share. We can draw this as a simple game tree: Keep all the money (0, 200) Me Trust me You Share (150, 50) Don’t (100, 0) This is a classic example of an agency game – there’s some surplus we can achieve together, but it requires you to trust me. But if we look at my incentives here once you’ve given me the money, I have no reason to give you your money back. Since you anticipate this problem, you refuse to trust me, so we miss out on this great opportunity. The important thing to note here is: it’s not just that you’re worse off because you can’t trust me; I’m worse off too, since my inability to commit to returning your money causes me to miss out on the investment as well. (One powerful way around this problem is to rely on reputation. That is, if this is a situation we find ourselves in over and over, it becomes valuable to me to be looked at as someone who is trustworthy; that way, you can keep investing your money with me, and we both do better. So if the game is to be repeated many times, we may be able to cooperate even when we could not in a one-shot game. The Friedman book gives the example of the diamond industry in New York, where disputes are never settled in court. There is a tight community of sellers (mostly orthodox Jews historically, now less so), everyone knows everyone, and reputation as an honest seller is vital. This is also part of the success of eBay – realizing that making sellers’ reputations public would give people a strong incentive to behave well. However, many interactions are “one-shot” – this is the only time I expect to deal with a person, and the incentives to maintain a good reputation may be too small.) What contract law does is give us one way to change this game into one that has a cooperative solution. Suppose we can sign a contract, under which I am punished if I run off with all the money. The punishment doesn’t have to be too severe – it just has to be bad enough that I’d rather share the gains rather than face the punishment. Suppose that the punishment is that a court steps in and forces me to give you back your $150, and charges each of us an additional $25 fee for doing so. This changes the game to: Keep all the money (125, 25) Me Trust me You Share (150, 50) Don’t (100, 0) Now there is a way for us to cooperate. After the investment, I’m better off giving you back your share of the money; so now you have a reason to trust me, and we get the benefit of the investment. So that’s the first purpose of contract law: to allow for efficient trade in situations where this requires some sort of commitment ability, that is, some way to make a promise credible. Of course, this begs a number of different questions, first among them, exactly what types of promises should be enforced by the law? The book motivates the question with three examples: 1. “The rich uncle of a struggling college student learns at the graduation party that his nephew graduated with honors. Swept away by good feeling, the uncle promises the nephew a trip around the world. Later the uncle reneges on his promise. The student sues his uncle, asking the court to compel the uncle to pay for a trip around the world.” 2. “One neighbor offers to sell a used car to another for $1000. The buyer gives the money to the seller, and the seller gives the car keys to the buyer. To her great surprise, the buyer discovers that the keys fit the rusting Chevrolet in the back yard, not the shiny Cadillac in the driveway. The seller is equally surprised to learn that the buyer expected the Cadillac. The buyer asks the court to order the seller to turn over the Cadillac.” 3. “A farmer, in response to a magazine ad for “a sure means to kill grasshoppers,” mails $25 and receives in the mail two wooden blocks with the instructions, “Place grasshopper on Block A and smash with Block B.” The buyer asks the court to require the seller to return the $25 and to pay $500 in punitive damages.” In a little while, we’ll start developing a theory of what contract law should look like for efficiency. But first… One of the early theories of contract law was developed in the late 1800s and early 1900s: the bargain theory of contracts. The bargain theory determined what promises would be held to be legally binding. The theory was: A promise should be enforced if it was given in a bargain, otherwise it should not. A bargain was taken to have three elements – that is, at its core, there are three things that must be present for a bargain to have occurred, and therefore for a promise to be enforceable under this theory: offer acceptance consideration “Offer” and “acceptance” are pretty clear. One of us approaches the other and offers some deal – “I’ll give you $1000 for that old car.” The other decides to accept. This is done differently in different situations. When you walk into a store and see price tags on goods, each of those is an offer to sell you that good at a given price. In an art auction, every time you raise your hand or nod to the auctioneer, you are making an offer to buy the piece up for sale; at some point, when there are no other bidders, the auctioneer accepts your offer. In most states, buying land requires a written contract, which functions as both offer and acceptance. On to consideration… We refer to the “promisor” as the person who gives a promise, and the “promisee” the person who receives it. In a bargain, both sides must be giving up something, so the promisee must be giving something to the promisor to induce the promise. It could be money – I give you $25 in exchange for the promise to give me a way to kill grasshoppers. It could be goods or services – you give me a car, or paint my house, in exchange for the promise of payment later. It could be another promise – a farmer promises to deliver a certain amount of wheat on a certain date, and a wholesaler promises to pay a certain amount at that time. “Money-for-a-promise”, “goods-for-apromise,” “service-for-a-promise”, “promise-for-a-promise” all refer to different types of bargains we could reach. The key is that both of us are giving up something. Bargains involve “reciprocal inducement” – the promisee gives something to the promisor to induce the promise, and the promisor gives the promise to induce the promisee to give up that thing. “Consideration” is the legal term for the thing the promisee gives the promisor to induce the promise. So the payment of $25, given to induce the promise of a way to kill grasshoppers, is consideration; giving up the car, or painting the house, is consideration for the promise of payment; and the promise of crops is consideration for the promise of payment. Under the bargaining theory of contracts, a promise becomes enforceable once consideration is given, that is, once the promisee gives something to the promisor in exchange for the promise. Going back to the examples at the beginning. When the rich uncle promised his nephew a trip around the world, no consideration was given – the nephew did not give him anything to induce the promise. So under the bargain theory, the promise is not enforceable. Promises of gifts are generally not enforceable under the bargain theory, since the promisee is not giving anything as inducement and therefore the promise is not part of a bargain. In the example of the disputed car, although consideration was given, the conditions of offer and acceptance were not met, since the seller was offering one thing and the buyer was accepting another. In Cooter and Ulen’s words, “Without a meeting of the minds, there is no offer and no acceptance, just a failure to communicate.” In the third example, the seller offered a method for killing grasshoppers, the buyer accepted the offer, and the payment of $25 acted as consideration; so under the bargain theory, this was a valid promise, and therefore enforceable. The bargain theory does not distinguish between fair and unfair bargains; that is, even a bargain that is extremely one-sided is considered enforceable under the bargain theory. It would be difficult, and costly, to enforce a theory that required the court to only enforce fair bargains, since the court would have to calculate the value of the contract to each party and determine what was “fair.” Thus, one way to make a gift promise enforceable is, instead of promising to give away something for free, selling it for $1. This makes the promise take the form of a bargain, and makes it enforceable under the bargain theory. (One example of a court’s refusal to examine whether a bargain was “fair,” and focus only on whether consideration was given, comes from an 1891 case, Hamer v Sidway (New York Court of Appeals). An uncle promised his nephew $5,000 to give up drinking and smoking until his 21st birthday. When the nephew turned 21, he refused to pay. The court wrote: The promisee [the nephew] used tobacco, occasionally drank liquor, and he had a legal right to do so. That right he abandoned for a period of years upon the strength of the promise of the [uncle] that for such forbearance he would give him $5,000. We need not speculate on the effort which may have been required to give up the use of these stimulants. It is sufficient that he restricted his lawful freedom of action within certain prescribed limits upon the faith of his uncle’s agreement, and now, having fully performed the conditions imposed, it is of no moment whether such performance actually proved a benefit to the promisor, and the court will not inquire into it.) (Modern courts, however, do sometimes refuse to enforce bargains that are completely one-sided. This is the doctrine of “unconscionability”, which we’ll come back to this.) Having answered the question of which promises should be enforceable, the bargain theory also answers the question of what the remedy should be when an enforceable promise is broken. Since the promisor agreed to the bargain, he owes it to the promisee to make him as well off as had the promise been fulfilled. Since the promise was not kept, however, it is sometimes impossible to calculate exactly what the benefits would be. Under the bargain theory, a promisor who breaches a promise owes the promisee “expectation damages” – the amount of benefit that the promisee could reasonably expect from the performance of the promise. This still leaves a lot of ambiguity sometimes. With the rich uncle and the college student, the benefit of the trip to the student would depend on the length of the trip, the route, and the quality of accommodations, which were not specified in the contract. The value to the farmer of a means of killing grasshoppers depends on the value of the crop that ended up being destroyed by them. There are also other problems with the bargain theory. First of all, it turns out not to be an accurate description of how courts actually behave, that is, which promises they tend to enforce. And second, it turns out not to be a good description of how efficiencyminded courts should behave. There are instances in which, at the time a promise is being made, both the promisor and promisee want the promise to be enforceable. The bargain theory says that such a promise is not enforceable unless it arises as part of a bargain. But such a promise may represent a Pareto-improvement, and therefore, an efficient legal system may need to enforce such promises. An example of this: suppose again I’m looking to buy a car, and I test-drive one, like it, but decide to look at a couple others as well. In order to get me to seriously consider the car, the seller might offer it to me at a particular price, and give me a week to decide – allowing me to test-drive a couple other cars, but keeping his in mind as an option. I’d like for this offer to be enforceable – I don’t want to come back a week later and find that he’s changed his mind. And he wants this offer to be enforceable – he knows that I’ll only take the offer seriously if I think it’s enforceable, and he wants me to take it seriously. So this is an instance where both sides want the promise to be binding; but because consideration was not given, the bargain theory would not enforce it. Another example: a rich alumnus promises a large donation to his university, to finance a new building; but it will take him time to liquidate some assets to actually deliver the donation. The university would like to begin construction immediately; and the alumnus, who wants the university to use the money optimally, also wants the university to begin to put the money to use immediately. But since the promise is not enforceable, the university can’t begin construction until the donation arrives. Again, both sides want the promise to be enforceable; but because a gift lacks consideration, the bargain theory would not enforce it. Other problems with the bargain theory – it is not all that accurate a description of what courts actually do; and it demands enforcement of certain promises that on many other grounds should not be enforced. So next, we’ll put aside the bargain theory and consider what efficiency would require of contract law. (Changing definition of “consideration”. Originally, something the promisee gives the promisor to induce the promise; which, under the bargain theory, makes the promise enforceable. But as time passed, exceptions began to arise. Eventually, rather than abandoning the bargain theory, the courts redefined “consideration” to be “the thing that makes a promise enforceable.” Thus, if a promise is not held to be enforceable, by definition consideration was lacking, which validates the decision that it should not be enforceable. Kind of useless…) In the rich alumnus example we just saw, both sides wanted the contract to be enforceable. This suggests that both sides think the contract being enforceable makes them better off. Neither of these contracts seem to impose any externalities on anyone else. So the enforceability of these contracts would appear to be a Pareto-improvement, that is, make the two sides better off without making anyone worse off. And therefore, efficiency suggests they should be enforceable. And this illustrates a more general principle: In general, economic efficiency requires enforcing a promise if the promisor and the promisee both wanted enforceability when it was made. Go back to the example we did at the beginning, you trusting me to make an investment with your money. Suppose I promise to share the gains of the investment with you. You want the contract to be enforceable: it’s the only way you’ll get your money back. And I want the contract to be enforceable: it’s the only way I can get you to trust me with your money, which is good for both of us. So we both want my promise to be enforceable; efficiency then suggests that it should be. There are lots of situations that are variations on this agency game. I gave the example of an investment opportunity. It could have simply been a Pareto-improving trade: I have a good you want, but we’re far apart, and so you have to trust me with your money before I ship you the good. It could be an insurance policy: I choose to buy insurance, trusting that if my house burns down, the insurance company will pay for it. I could simply be putting my money in the bank, trusting I can get it out later. In all these cases, a lack of enforceable contracts might lead us to forego a profitable exchange of some sort. This brings us to Cooter and Ulen’s first (of many) proclamations about the purpose of contract law: The first purpose of contract law is to enable people to cooperate by converting games with noncooperative solutions into games with cooperative solutions. Clearly, in the example we did, cooperation is more efficient than no cooperation, since the combined payoffs are higher; thus, in this case, cooperation is efficient. (If cooperation were not efficient, we would not have tried.) Thus, we could rephrase this by saying that contract law enables people to convert games with inefficient solutions into games with efficient solutions. Also note that without enforceable contracts, it is my ability to run off with your money that causes cooperation to break down. In usual choice theory, more options always make you better off. When a restaurant adds items to its menu, you should be at least as well off – if you don’t like the new items, you don’t order them. But in a strategic setting, more options can make you worse off, since they change what other people expect you to do. Enforceable contracts give me a way to limit my options – in this case, to take away my ability to run off with your money. In this case, limiting my options gives you a reason to trust me, and therefore makes me better off as well. (Slightly off topic, but as an example of how “foreclosing (ruling out) an opportunity” can be beneficial, the book quotes Sun Tzu’s The Art of War: “When your army has crossed the border [into hostile territory], you should burn your boats and bridges, in order to make it clear to everybody that you have no hankering after home.” By taking away your option of retreating, you make it clear that you’re serious about fighting.) This gives us a nice first pass at which promises should be enforceable: those which both the promisor and the promisee want to be enforceable when the promise is made. And it suggests one purpose of contract law: to enable cooperation by changing a game to have a cooperative solution. However, there are a number of other purposes that contract law can serve.. One has to do with information. We mentioned earlier in the course that asymmetric, or private, information can get in the way of beneficial trade. Consider the example of one of you wanting to buy my car. You really need a car, so you figure that whatever my car is worth to me, it’s worth 50% more than that to you. So whatever the car is worth, there are clearly gains from trade. However, I know exactly what the car is worth, and you don’t; all you know is that it’s worth somewhere between $0 and $5000, and any value within that range is equally likely. Even worse, there are no mechanics available and you know nothing about cars, so there’s no way for you to figure out its true value. So how are you going to buy this car from me? Well, you know that on average, the car is worth $2500 to me, and you value it at 50% more than me; so suppose you decide to offer me $3000. What happens? Well, if you offer me $3000 for my car, I’ll sell it to you when it’s worth less than $3000 to me, and when it’s worth more than $3000 to me, I’ll say no. So you can expect to only get the car when it’s worth less than $3000, so the times that I sell it to you, it will be worth, on average, $1500 to me, and therefore $2250 to you. So you’re losing money. But the less money you offer me, the less the car will be worth in the event that I choose to sell it to you. In this case, unless there is some way for us to verify the value of the car, there is no price you’re willing to offer me for the car. So even though the car is worth more to you then me, due to asymmetric information, we are unable to transact. (This example comes from a famous paper by George Akerloff, “The Market for Lemons.” It’s also exactly the same problem as adverse selection in insurance markets.) So this gives another way that contract law can facilitate efficient trade. Contract law could impose on me a legal obligation to truthfully tell you anything I know about the condition of the car. That is, once we’ve signed a contract for you to buy my car, contract law could make me liable for any mechanical problems with the car that I didn’t warn you about. In this case, requiring me to share information is efficient, since it reduces your uncertainty about the value of the car, and therefore gives us a way to trade. Which brings us to… The second purpose of contract law is to encourage the efficient disclosure of information within the contractual relationship. (We’ll come back to this when we come to applications of contract law.) We will also need to address the question of enforcement, that is, what should be the remedy for breaking a legally enforceable promise? In the first example we gave – the investment opportunity – it doesn’t really matter; all that matters is that the remedy be severe enough that I don’t run off with your money. However, there are situations in which, after a contract is signed, it becomes efficient for it to be broken. This is the idea of efficient breach. And in those cases, the remedy becomes very important. Consider a situation where I am working on a painting. It’s still a couple of weeks away from completion, but you’ve seen my work before, and you like my theme, and you know that when I’m done, you’ll value my painting at $1000. There are other buyers out there who might value it similarly, so you don’t want to wait until it’s done to buy it; but I’m happy to sell it to you, and we agree on a price of $600. But now, as I’m finishing the painting, my crazy cousin comes to visit, and sees my painting, and loves it, and thinks the colors would go perfectly in his beach house, and offers me $5000 for it. Clearly, he values the painting much more highly than you do. Efficiency would require that he get it. But I’ve already committed to sell the painting to you. (In some instances, you could just resell the painting to him. But in some cases, that won’t work – he’s crazy, and only wants to buy it from me, or he’s leaving town tomorrow and you’re not around.) The efficient thing, then, is for me to breach my contract with you, because the cost of performing – in this case, the opportunity cost of selling the painting to you instead of my cousin – is higher than the benefit you will get from the painting. (Of course, if we foresaw the possibility of my cousin wanting the painting, we could have written that into the contract. However, it’s often impossible, or at least unrealistic, to foresee and contract for every possible contingency. Much of contract law is figuring out what to do in situations the parties to the contract didn’t consider.) There are many instances where breaching a contract might be efficient. Suppose I build airplanes, and you contract to buy one from me. You value the plane at $500,000, and we agree to a price of $350,000. Now before I begin construction, the price of sheet metal goes through the roof, and building the plane would cost me $1,000,000. Clearly, it’s inefficient for me to have to live up to my end of the contract. If we’re on good terms, it’s possible we could renegotiate – you agree to let me off the hook in exchange for some payment. But if we can’t agree, I’m facing a loss of $650,000; so I’m in a pretty bad bargaining position, and you can demand pretty large compensation to let me off the hook, even more than the contract was originally worth to me! And if I anticipate that there’s a chance this could happen, it might discourage me from ever agreeing to the contract in the first place. In general, if the promisor’s cost of performing is higher than the promisee’s benefit from performance of the contract, it is efficient to breach the contract. If the promisor’s cost of performing is lower, it’s efficient to perform (to live up to the promise). And this is where the choice remedy becomes important. If the punishment for breach of contract is too severe, the promisor will have to perform, even when it would be efficient to breach. If the punishment is too light, of course, the promisor will breach when efficiency would require performance. (Suppose, for example, that after you contract to buy something from me, something happens that makes the product more expensive for me to produce but also more valuable to you, such that it is still efficient for me to produce it, even though I may no longer be so excited about the price we agreed on.) Self-interest suggests that I will choose to breach whenever the cost of performing is higher than my liability from breaching. And efficiency suggests that I should breach whenever the cost of performing is higher than the promisee’s benefit from my performing. This means that self-interest will lead to efficiency if my liability from breaching is exactly the promisee’s benefit if I had performed. This is what happens under perfect expectation damages – my liability is exactly equal to the benefit the promisee would have received had I performed. So under perfect expectation damages, my liability causes me to exactly internalize the cost of breach, and leads me to make efficient decisions about performing. Which brings us to… The third purpose of contract law is to secure optimal commitment to performing. Perfect expectation damages lead to breach of contract only when it is efficient. reliance But now things get a little bit more complicated. Suppose that you’ve contracted to buy my painting. Anticipating it, you might go out and buy a frame for it, or install track lighting, or buy furniture that will go well with the colors – you make investments that will enhance the value of me holding up my end of the contract. Similarly, if you’ve contracted to buy an airplane from me, you might start building a hangar, so that the plane doesn’t get rained on once it’s delivered. Similarly, the farmer who has mailed in a check for $25 for a sure means to kill grasshoppers might decide he can now plant more crops, since the risk of grasshopper damage has been mitigated; the nephew who’s been promised a trip around the world might go out and buy a backpack, or a linen suit to wear in the tropics. All of these are examples of reliance – investments that increase the value of performance to the promisee. In many cases, making these investments early is efficient – if you wait to build a hangar until I deliver your airplane, it might get damaged in a snowstorm before the hangar is complete; if the nephew waits to buy a linen suit until his uncle sends him plane tickets, he might miss a big spring sale. On the other hand, we’ve introduced the notion of efficient breach, and the idea that the promisor may not always perform (and that this may be OK); which means that reliance is not a sure thing. Reliance will generally increase the losses due to breach – you’ve built a hangar for nothing, or you resell your backpack and linen suit at a loss. Which brings us to: The fourth purpose of contract law is to secure optimal reliance. The expected gain from reliance is the probability that the promisor performs, times the increase in the value of performance; efficiency suggests that reliance should increase as long as (probability of performance) X (increase in value) > (incremental cost) However, suppose that the promisor, upon breach, has to reimburse the promisee for the value of performance after the increased reliance. (Simple perfect expectation damages force the promisor to make the promisee as well off as if he had performed; so once the promisee has made these additional investments, this is a higher level.) Then after damages, the promisee will get the value of performance (with reliance), even when the contract is breached. If the promisor’s liability includes the benefits of reliance, then the promisee has an incentive to increase reliance as long as Increase in value > incremental cost This means that such a rule would lead to overreliance – the promisee would make inefficient investments in increasing the value of performance, since he is insulated from the risk of breach. Tuesday, we’ll continue with an example of optimal reliance, and how the law can be designed to achieve it.