Econ 522 – Lecture 14 (Oct 23 2007)

Econ 522 – Lecture 14 (Oct 23 2007)

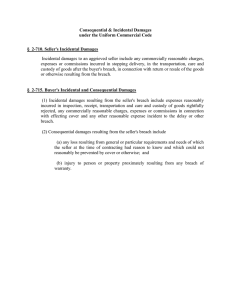

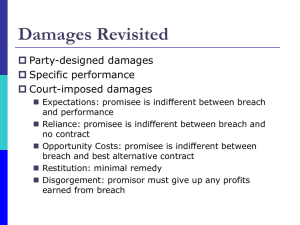

Last Thursday, we looked at the different types of remedies a court could impose for breach of contract. In particular:

Expectation damages, designed to replace the value of performance

Opportunity cost damages, designed to replace the value of the next-best alternative forgone by the promisee

Reliance damages, designed to only replace the value lost by the promisee due to reliance

Specific performance – requiring the promisor to honor the promise rather than imposing damages

Today, we’ll look more carefully at the different incentives created by each, and in particular how they influence the following three decisions:

the promisor’s decision to perform or breach

the promisor’s investment in performing, and

the promisee’s investment in reliance

Put aside the question of reliance for the moment, and suppose that performance of the promise will have a fixed benefit for the promisee. The fact that the two parties agreed to the contract in the first place implies they believed this benefit was likely to greater than the cost to the promisor of performing. However, as we’ve already discussed, circumstances may change after the promise is made, in a way that makes the promisor less keen to keep his promise. (The price of building the airplane may go up, or my rich cousin may appear and value my painting more highly than you do.)

There are two ways for me to get out of my promise: I can renegotiate with you, getting you to “let me off the hook,” presumably in exchange for some money. Or I can breach our contract and live with the consequences, most likely the damages that a court imposes.

Think back to nuisance law. Recall that when an entitlement (say, the right to breathe clean air) was protected by injunction, the parties could still bargain for it – the polluter could offer the neighbor enough money to be willing to live with the pollution. When an entitlement was protected by damages, the polluter could instead simply pollute and pay whatever damages were ordered. We found that when transaction costs were low, either remedy would lead to efficiency; but since the two remedies changed the noncooperative outcome (the outside option) for each side, they led to different allocations of surplus.

On the other hand, when transaction costs were high, the two remedies could lead to different results.

Here, the story is exactly the same. Consider a promise that is enforced by specific performance – the promisor is not allowed to breach unless the promisee agrees – versus a promise enforced by, say, expectation damages. When transaction costs are low, either one will lead to efficient breach; but the allocation of surplus to the two parties will be different. And when transaction costs are high, they may lead to different outcomes.

Let’s continue beating to death the example of the airplane I agreed to build for you. The plane will give you a value of $500,000, and we agree on a price of $350,000; I expect the plane to cost me $250,000 to build, but there is some chance it will instead cost me

$1,000,000.

First, let’s consider what happens if our contract is protected by expectation damages.

I Get

You Get

Total

Costs Low

(Perform)

100,000

150,000

250,000

Costs High

(Perform)

-650,000

150,000

-500,000

Costs High (Breach, pay exp damages)

-150,000

150,000

0

Now let’s see what happens if our contract is protected by specific performance, that is, you have the right to demand the airplane, and I can only breach with your permission.

I Get

You Get

Costs Low

(Perform)

100,000

150,000

Costs High

(Perform)

-650,000

150,000

Costs High

(renegotiate)

Total 250,000 -500,000 0

Since performance is very costly, my outside option is very bad, so renegotiation may force me to accept fairly bad terms. Notice that by renegotiating the contract, we create a total surplus of $500,000 (beyond our outside options if you forced me to build the plane). Suppose that our negotiations lead us to divide this additional surplus evenly.

This would lead you to get $250,000 beyond your outside option, which was $150,000, so your payoff would be $400,000; I would get $250,000 beyond my outside option, which was -650,000, which would be -400,000.

So as long as transaction costs are low, either remedy will lead to the same outcome.

When it is efficient to breach, expectation damages lead me to breach without permission; and renegotiation will lead us to some sort of agreement to let me off the hook.

Of course, when the transaction costs of renegotiating our contract are too high, specific performance would lead to inefficient performance – I would have to build you the plane, even though it costs me more than your benefit – while expectation damages would still allow me to breach.

Other types of damages – opportunity cost damages, or reliance damages – would lead to inefficient breach, that is, I would choose to breach even when my cost of performing is lower than your benefit. However, when transaction costs are low, this could also be fixed through renegotiation.

To see an example of this, consider the same situation, but now suppose that the next-best contract would have sold you a similar plane for $400,000, but that now at this late date, no other planes are available. We agreed on a price of $350,000, but now costs go up somewhat, to $460,000.

Perform Breach and pay Opp

Cost Damages

Renegotiate and

Perform

I Get

You Get

-110,000

150,000

-100,000

100,000

P – 460,000

500,000 – P

Total 40,000 0 40,000

Renegotiating generates additional surplus of $40,000; if we split this evenly, we would each get a payoff $20,000 higher than our outside option, which would require the renegotiated price to be $380,000.

Again, however, if transaction costs were high, we would be unable to renegotiate the contract, and I would choose to breach and pay you $100,000 in opportunity cost damages.

(Cooter and Ulen point out that, just like efficiency demands enforcing contracts whenever the parties wanted them to be enforceable, efficiency demands enforcing renegotiated contracts whenever the parties wanted them to be enforceable at the time of renegotiation.)

So just like with nuisance law, we find the following:

if it is cheap/easy to renegotiate terms, any of the remedies will lead to efficient breach, although they will lead to different allocations of surplus

if it is expensive/hard to renegotiate terms, only expectation damages are guaranteed to lead to efficient breach – specific performance may lead to inefficient performance, and lower damages may lead to inefficient breach

An increase in the cost of performance is referred to as an unfortunate contingency . On the other hand, I may be less keen to keep my promise because I discover another buyer who values my product more than you do. This is referred to as a fortunate contingency . Earlier, we saw the example where you contracted to buy my painting, but my rich cousin appeared and valued it much more highly than you did. We can do the same exercise as before with the different remedies, and see the same thing – with low transaction costs, any remedy will lead to efficient breach, but with different allocations of surplus. This is done in the book (p. 267). Once again, specific performance is the most advantageous to the buyer, and higher damages are better for the buyer than lower damages.

So that’s breach. What’s left is investment in reliance

, which we’ve already talked a bit about; and investment in performance

, which we haven’t.

The book makes a big deal out of “ the paradox of compensation

,” which is basically what we already talked about earlier: the remedy for breach sets an incentive for both the promisor and the promisee, and it’s generally impossible to set both of these incentives efficiently at the same time.

It will be easiest to see this with an example. Let’s go back to the airplane example once again, and again assume that, once you contract to buy my plane, you consider building yourself a hangar. But this time, rather than just a decision to build or not build, there is a whole range of different-quality hangars you could elect to build.

Suppose that, for any investment of x dollars, you can build a hangar that will enhance the value of having a plane by 600 sqrt(x) , but is worthless without a plane.

Investment Value of

Hangar x

100

10,000

600 sqrt(x)

6,000 Large tarp held up by some rope connected to a telephone pole – still keeps some rain off the airplane

60,000 Basic plywood frame, canvas roof

40,000

160,000

120,000 Metal poles, rigid roof

240,000 Functional heating

640,000 480,000 Designer hangar with working Starbucks

Recall that whatever investment is made in reliance pays off when the promise is kept, but is lost when the promise is broken.

Suppose that expectations damages include the benefits anticipated based on reliance investments. Then the buyer would maximize

500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 350,000 – x since he gets the same benefit whether or not the seller breaches; solving this gives the first-order condition

600/2sqrt(x) – 1 = 0

x = 300^2 = 90,000 so the buyer, when insulated from the risk of breach, invests $90,000 in a reasonably nice hangar, giving anticipated benefit of 600 sqrt(90,000) = 180,000.

What is the efficient level of reliance? The total social gain from the contract is

500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 250,000 – x without breach, and –x with breach (the reliance investment is lost, and other than that, all that happens is transfers). Suppose the probability of breach is p; then the expected social benefit is

(1-p) (500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 250,000) – x which leads to an efficient level of reliance equal to 90,000 (1-p)^2.

So for any p > 0, damages which include benefits from reliance lead to overreliance, that is, investment in reliance that is higher than what would be efficient.

On the other hand, suppose expectation damages did not include the benefits of reliance.

Then the buyer maximizes

(1-p) (payoff without breach) + p (payoff with breach) =

(1-p) (500,000 + 600 sqrt(x) – 350,000 – x) + p (150,000 – x) =

150,000 + (1-p) 600 sqrt(x) – x which leads to the same (efficient) level of reliance.

So if the level of damages includes the gains from reliance, this leads to overreliance; if the level of damages excludes the gains from reliance, this leads to efficient reliance.

(Recall that Cooter and Ulen hoped for damages which included the gains only from

“efficient” reliance, which is a nice idea but incredibly hard to measure after the fact…)

But we also know that if the level of damages exclude the gains from reliance, and the buyer relies anyway, that this will lead to inefficient breach. That is, since the seller’s liability from breach is lower than the buyer’s gain from performance, there will be some instances where the seller breaches even though efficiency requires performance.

We said before that with no transaction costs, this problem can be solved: when breach would be inefficient, the parties can contract around it. Since it’s generally very clear whether a party has breached a contract or not, this shouldn’t be a particular problem.

However, there are situations in which a promisor can take actions to make performance less costly, or, to put it another way, to lessen the probability that breach is efficient. A contractor could buy raw materials ahead of time, to avoid the risk of changing prices; a manufacturer could start a project earlier and frontload the labor to avoid the risk of a strike. If a project were to require a building permit or zoning easement, he could lobby the local government (or bribe someone) to decrease the chances of hitting a snag.

This sort of investment in performance, however, may be unobservable, or unverifiable; and therefore, even when this sort of investment is efficient, it may be very hard to build it into the contract. (It’s very hard to enforce a contract specifying “how hard I have to try” to convince the zoning board to approve your project.) Thus, investment in performance may only occur when it is in the promisor’s best interest.

Go back to the airplane example, and suppose there is some investment I can take that reduces the chance that my costs go up. (I can buy some of my supplies ahead of time, but I can’t completely insulate myself from risk.) Suppose that for each $27,726 I invest, i can reduce the probability I will need to breach by ½. That is, if I invest $27,726, the probability of breach goes from ½ to ¼. If I invest another $27,726, it goes down to 1/8.

And so on.

For any investment z, then, we can write the probability that breach is still required as

½ * ½ ^(z / 27,726)

The reason I chose the number 27,726 is that we can rewrite this probability as

½ e^{- z/40,000)

Which makes it much easier to work with.

So, how much would a self-interested promisor invest in performance? Go back to the airplane example, and let D be the amount of damages that the promisor is liable for if he breaches. (D could be nothing; or the investment in reliance; or the opportunity cost; or the gain the buyer expected to achieve, with or without reliance.) Suppose only that D is low enough that breach is still preferable when costs go up. (Since we’ve been talking about costs rising to 1,000,000, this just requires D < 650,000, the loss I would take from performing.)

When costs remain low, the seller expects $100,000 in profits. So when deciding how much to invest in performance, the seller maximizes

(1 – Pr(breach)) 100,000 + Pr(breach) (-D) – investment in performance

= 100,000 – Pr(breach)(D + 100,000) – z

= 100,000 – ½ e^(-z/40,000) (D+100,000) – z

Taking the derivative gives ½ 1/40,000 e^(-z/40,000) (D+100,000) – 1 = 0 or ½ e^(-z/40,000) = 40,000/(D+100,000) so the seller invests enough to reduce the probability of breach to 40,000/(D+100,000)

So if the seller can breach for free, he’ll invest enough to reduce the probability of breach from ½ to 40,000/100,000 = 2/5. He still prefers profits (100,000) over nothing, but he only invests a little, since he can still get out of the contract for free. (The investment here is about $9,000.)

Suppose D were expectation damages, without reliance, If he would owe expectation damages (without reliance) of $150,000, then he invests enough to reduce the chance of breach from ½ to 40000/(150,000+100,000) = 4/25. (The investment this time is about

$45,000.)

Suppose D were expectations damages, with reliance. We said that if expectation damages include reliance, the buyer spends $90,000 on a hangar giving $180,000 in benefits, so his benefit from performance is now 500,000 – 350,000 + 180,000 =

330,000. With damages at level, the seller invests enough to reduce the probability of breach to 40,000/(330,000 + 100,000) = 40/430. (The investment to do this is about

$67,000.)

But what would be efficient? Suppose that the buyer has already decided to build himself that nice $90,000 hangar. So the benefit of performance is 330,000. The cost of the hangar is sunk, so we can forget about it for now.

The total social surplus is

(1 – Pr(breach)) (330,000 + 100,000) + Pr(breach) (0) – z

= 430,000 – 430,000 ½ e^(-z/40000) – z

To maximize this, we take the derivative:

430,000 ½ 1/40,000 e^(-z/40000) – 1 = 0

Pr(breach) = 40,000/430,000

So given that level of reliance, the efficient level of investment in performance is enough to reduce the chance of breach to 40,000/430,000.

Which we just saw is exactly what the seller would do when he’s liable for expectation damages which include the benefit from reliance!

To sum up, the efficient level of investment leads to a 40,000/430,000 chance of breach.

Damages which are set equal to D lead to a self-interested promisor to allow a probability of breach of 40,000/(D + 100,000). So when damages are set to 330,000 – benefit including reliance – the investment in performance is efficient. When damages are lower, the seller will underinvest in performance, leaving the risk of breach inefficiently high. (When damages are higher than this, the seller will overinvest in performance.)

So what have we found? Making the seller liable for reliance – that is, increasing expectation damages to include benefit due to reliance – leads the seller to invest efficiently in performance; but it leads the buyer to overinvest in reliance.

On the other hand, making the seller not liable for reliance – leaving expectation damages where they were without reliance – leads to efficient reliance, but leads to underinvestment in performance. (We saw before that even if expectation damages do not include reliance, the buyer still chooses to rely some, just less; so D < benefit, and the seller underinvests in performance.)

So like we saw last week with the sailboat example from Friedman, the level of damages leads to multiple different incentives; and it’s mighty tough to set a level of damages that makes everyone behave efficiently.

anti-insurance

The textbook discusses one rather clever solution to this problem. It’s not all that realistic, but it is clever, and it’s worth mentioning.

We saw that, in order for you to invest the efficient amount in reliance, you need to receive damages that do not include the benefit from reliance.

And we saw that, in order for me to invest the efficient amount in performance, I need to owe damages that do include the benefit from reliance.

How can we can accomplish both these things? Well, we can set the level of damages that I pay to be different from the level of damages that you receive!

You and I have this friend, Bob. Bob likes money. So we go to Bob and say, hey Bob, here’s a deal for you. I’m planning to build a plane. He’s planning to buy the plane.

He’s probably going to want to build a hangar. I might end up not building the plane.

Here’s what we need you to do.

In the event that he builds a hangar and I don’t build the plane, I’m going to give you the value of the plane with the hangar; and you’re going to give him the value of the plane without the hangar; and you’re going to keep the rest for yourself. OK?

And Bob says, “cool!”

This is called “anti-insurance”. Rather than buying insurance from a third party, you and

I are basically entering into this additional contract where if things go bad, I owe Bob some additional money, beyond what I pay you.

By doing this, we set both our incentives correctly, so we get efficient reliance and efficient investment in performance.

Now obviously, Bob is happy to do this for free. But now we go to our other friend

Carol, and say, Hey, Carol. Here’s a deal we’re offering. Give us $5 now, and if he builds a hangar and I don’t deliver a plane, you’ll get the difference between the value of the plane with the hangar and without the hangar.

And Carol realizes this is worth more than $5, so she says, “sure.”

But now we go back to Bob, and we offer him the deal at $10 instead.

And if we make Bob and Carol compete for this deal, we should be able to get them to pay a fair amount for it up front. If they’re risk averse, of course, they’ll need to be compensated for taking on some risk; but if we have a risk-neutral friend who’s smart enough to understand the probabilities and figure out what each of us will do given our incentives, we can get them to give us the full value of the anti-insurance deal ahead of time, and divide it up among ourselves.

So this way, we can give ourselves incentives for efficient reliance and efficient investment in performance at the same time.

There are other ways to get around the problem. We already introduced the notion of basing damages, not on the benefit expected under the actual level of reliance, but on the benefit expected under the hypothetical “efficient” level of reliance. If we write this into the contract (and are able to calculate it correctly), then we can use expectation damages with reliance to set the seller’s incentives correctly, while still not causing the buyer to overrely.

This could either be done explicitly in the contract – we agree that I have to pay expectation damages up to the value you would receive from a $60,000 hangar but not more than that – or it could be imposed by the court after the fact.

As we mentioned before, what courts actually do, rather than basing damages on actual or on efficient reliance, is to base damages on foreseeable reliance. That is, they base damages on what the promisor could reasonably expect the promisee to do, not what he actually did. This was the decision in Hadley: since the shipper could not reasonably expect the miller to rely so heavily, he was not liable for the lost profits. (Apparently, most millers at the time had more than one crankshaft., so a broken shaft would not typically lead to shutdown.)

Of course, under the doctrine of foreseeable reliance, if Hadley had told Baxendale that his mill was closed until repairs were made, then Baxendale would be liable for lost profits due to delay; by informing Baxendale of the reliance, Hadley would have made it foreseeable, and therefore compensable.

One final point for today: timing .

Everything we’ve done so far has assumed that the timing of the contract is fairly rigid: first, we sign a contract. Next, you decide how much to rely, and I decide how much to invest in performance. Then, I decide whether to perform or breach, and if I breach, I pay damages.

But often, the different stages may overlap a bit more. If I’m building a house for you,

I’m unlikely to build it in a day; you may be able to see how some of the progress is going before making all of your reliance investments.

Similarly, the question of when someone decides to breach a contract may affect the damage done by breach, which may therefore affect damages.

Suppose you’re a farmer, and I’m a grain wholesaler, and you agree to deliver me 10 tons of corn on a given date at a given price. This is a futures transaction – a promise to transact a good on a future date. In some cases, there may be a going market rate for corn delivered on that date. And this price can rise or fall as the date approaches.

So we agree that you’ll sell me 10 tons of corn next June, at a price of (I don’t know the price of corn), say, $500 per ton. Over the course of the winter, circumstances may change – maybe it’s a dry winter, so irrigation will be more expensive in the spring; maybe other crop prices go up and you decide to plant wheat in more of your field.

If you decide to breach, you could wait until the last minute to tell me – in which case, damages might reflect the cost to me of buying corn on the spot market, that is, the day I was expecting delivery.

Alternatively, you could tell me in January that you plan to breach our contract. This would allow me to contract in advance with someone else to sell me corn in June, which might be cheaper than if I waited till the last minute.

Breaching a contract in advance on is sometimes called “renouncing” or “repudiating” a contract – you announce early your intention to breach. When this happens, if there is a market for a substitute good – in this case, June corn – then damages would reflect the price of June corn futures at the time you renounced the contract, say, in January.

I could actually buy the futures in January, or I could wait and take my chances; but what happens after that tends not to affect the damages you owe me.

To use another example from last week, suppose one of you agreed last Monday to sell me a ticket to the Wisconsin-Northern Illinois game for $50. At the time we agreed to the deal, there were lots of tickets available for $75. If you breached early in the week, I could have bought a replacement ticket for $75; so expectation damages would be limited to $25, the damage breaching early did to me relative to performing.

If I chose not to buy another ticket in advance, and waited and overpaid on the morning of the game, that was a risk I chose to take, but not your responsibility.

(Of course, in cases where there is a liquid market for substitutes, there’s little difference between you renouncing our agreement and paying damages, or you going out and buying another ticket on Craigslist to sell to me at our agreed price. If transaction costs are low, the two are equivalent. So when there is a market for a substitute good and transaction costs are low, you are indifferent between breaching and paying damages, and buying and delivering a substitute product.)

(In well-behaved markets, futures prices are generally assumed to reflect the market’s expectation about what the future spot price of the good will be. That is, if everyone knows there will be a liquid market for tickets at $150 at the end of the week, there’s no reason for them to be selling for $75 early in the week; under certain conditions, futures prices should just be the expected value of the future spot price. So in terms of the expected payoffs, and the incentives to breach, there shouldn’t be a difference whether courts impose damages equal to the futures price at the time a contract is renounced, or equal to the spot price realized at the date of promised delivery.)

When goods are traded that do not have close substitutes, however, the value is sometimes hard to calculate, so courts sometimes impose only reliance damages simply because it’s easier. Renouncing a contract earlier obviously stops the promisee from making further investments in reliance. However, when damages are set lower then the benefits of performing, we’ve seen before that this will lead to inefficient breach.

(There are some further complications – the law on anticipatory breach, and breach following partial performance, are a little bit murky. In some of these cases, renegotiation of the contract may be preferable to outright breach; again we come to the suggestion that efficiency demands enforcing renegotiated contracts as long as both parties wanted it enforceable at the time of renegotiation.)

The last two days, we’ve focused on the question of what remedy should be given when a promise is broken. Thursday, we’ll go back to the other question contract law needs to answer, which promises should be enforced? We’ll look at formation defenses and performance excuses, and wrap up contract law.