Econ 522 Economics of Law Dan Quint Fall 2010

advertisement

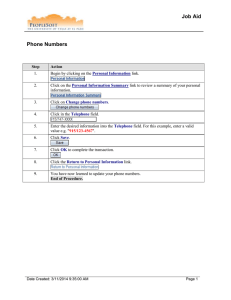

Econ 522 Economics of Law Dan Quint Fall 2010 Lecture 5 Monday… Coase Theorem: in the absence of transaction costs, if property rights are well-defined and tradable, we’ll always get efficiency Or: if property rights are complete enough, we can overcome externalities Or, if conditions are perfect, initial allocation of rights doesn’t matter (for efficiency) But if there are transaction costs, this breaks down Today: Demsetz – when will property rights expand? Transaction costs 1 Demsetz 2 ORIGINAL GAME MODIFIED GAME Player 2 Player 2 Farm Steal Farm 10, 10 -5, 12 Steal 12, -5 0, 0 Farm Player 1 Player 1 We motivated property law by looking at a game between two neighboring farmers Steal Farm 10 – c, 10 – c -5 – c, 12 – P Steal 12 – P, -5 – c -P, -P Changing the game had two effects: Allowed us to cooperate by not stealing from each other Introduced a cost c of administering a property rights system 3 Harold Demsetz (1967), “Toward a Theory of Property Rights” “A primary function of property rights is that of guiding incentives to achieve a greater internalization of externalities” “[ In order for an externality to persist, ] The cost of a transaction in the rights between the parties… must exceed the gains from internalization.” “Property rights develop to internalize externalities when the gains from internalization become larger than the cost of internalization.” 4 Harold Demsetz (1967), “Toward a Theory of Property Rights” “Property rights develop to internalize externalities when the gains from internalization become larger than the cost of internalization.” Private ownership of land among Native Americans Cost of administering private ownership: medium Before fur trade… externality was small, so gains from internalization were small gains < costs no private ownership of land 5 Harold Demsetz (1967), “Toward a Theory of Property Rights” “Property rights develop to internalize externalities when the gains from internalization become larger than the cost of internalization.” Private ownership of land among Native Americans Cost of administering private ownership: medium Before fur trade… externality was small, so gains from internalization were small gains < costs no private ownership of land As fur trading developed… externality grew, so gains from internalization grew gains > costs private property rights developed 6 Friedman tells a similar story: “we owe civilization to the dogs” The date is 10,000 or 11,000 B.C. You are a member of a primitive tribe that farms its land in common. Farming land in common is a pain; you spend almost as much time watching each other and arguing about who is or is not doing his share as you do scratching the ground with pointed sticks and pulling weeds. …It has occurred to several of you that the problem would disappear if you converted the common land to private property. Each person would farm his own land; if your neighbor chose not to work very hard, it would be he and his children, not you and yours, that would go hungry. 7 Friedman tells a similar story: “we owe civilization to the dogs” There is a problem with this solution… Private property does not enforce itself. Someone has to make sure that the lazy neighbor doesn’t solve his food shortage at your expense. [Now] you will have to spend your nights making sure they are not working hard harvesting your fields. All things considered, you conclude that communal farming is the least bad solution. 8 Friedman tells a similar story: “we owe civilization to the dogs” Agricultural land continues to be treated as a commons for another thousand years, until somebody makes a radical technological innovation: the domestication of the dog. Dogs, being territorial animals, can be taught to identify their owner’s property as their territory and respond appropriately to trespassers. Now you can convert to private property in agricultural land and sleep soundly. Think of it as the bionic burglar alarm. -Friedman, Law’s Order, p. 118 9 So… Coase: if property rights are complete and tradable, we’ll always get efficiency or, we can eliminate externalities by introducing trade in missing markets – that is, by making property rights more complete Demsetz: yes, but this comes at a cost property rights will expand when the benefits outweigh the costs either because the benefits rise… …or because the costs fall The costs Demsetz was talking about are straightforward… …but let’s go back to the transaction costs of Coase 10 Transaction Costs 11 What are transaction costs? Anything that makes it difficult or expensive for two parties to achieve a mutually beneficial trade Three categories Search costs – difficulty in finding a trading partner Bargaining costs – difficulty in reaching an agreement Enforcement costs – difficulty in enforcing the agreement afterwards 12 Bargaining costs come in many forms Asymmetric information Akerloff (1970), “The Market for Lemons” – adverse selection 13 Bargaining costs come in many forms Asymmetric information Akerloff (1970), “The Market for Lemons” – adverse selection Private information (don’t know each others’ threat points) Myerson and Satterthwaite (1983), “Efficient Mechanisms for Bilateral Trading” – always some chance of inefficiency 14 Bargaining costs come in many forms Asymmetric information Akerloff (1970), “The Market for Lemons” – adverse selection Private information (don’t know each others’ threat points) Myerson and Satterthwaite (1983), “Efficient Mechanisms for Bilateral Trading” – always some chance of inefficiency Uncertainty If property rights are ambiguous, threat points are uncertain, and bargaining is difficult 15 Bargaining costs come in many forms Large numbers of parties Developer values large area of land at $1,000,000 10 homeowners, each value their plot at $80,000 16 Bargaining costs come in many forms Large numbers of parties Developer values large area of land at $1,000,000 10 homeowners, each value their plot at $80,000 Holdout, freeriding Hostility 17 Sources of transaction costs Search costs Bargaining costs Asymmetric information/adverse selection Private information/not knowing each others’ threat points Uncertainty about property rights/threat points Large numbers of buyers/sellers – holdout, freeriding Hostility Enforcement costs 18 So, what do we do? 19 What we know so far… No transaction costs initial allocation of rights doesn’t matter for efficiency wherever they start, people will trade until efficiency is achieved Significant transaction costs initial allocation does matter, since trade may not occur (and is costly if it does) This leads to two normative approaches we could take 20 Two normative approaches to property law Design the law to minimize transaction costs “Structure the law so as to remove the impediments to private agreements” Normative Coase “Lubricate” bargaining 21 Two normative approaches to property law Design the law to minimize transaction costs “Structure the law so as to remove the impediments to private agreements” Normative Coase “Lubricate” bargaining Try to allocate rights efficiently to start with, so bargaining doesn’t matter that much “Structure the law so as to minimize the harm caused by failures in private agreements” Normative Hobbes 22 Which approach should we use? Compare cost of each approach Normative Coase: cost of transacting, and remaining inefficiencies Normative Hobbes: cost of figuring out how to allocate rights efficiently (information costs) When transaction costs are low and information costs are high, structure the law so as to minimize transaction costs When transaction costs are high and information costs are low, structure the law to allocate property rights to whoever values them the most 23 Designing an efficient property law system 24 Four questions we need to answer what can be privately owned? what can an owner do? how are property rights established? what remedies are given? 25 Calabresi and Melamed treat property and liability under a common framework Calabresi and Melamed (1972), Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral Liability Is the rancher liable for the damage done by his herd? Property Does the farmer’s right to his property include the right to be free from trespassing cows? Entitlements Is the farmer entitled to land free from trespassing animals? Or is the rancher entitled to the natural actions of his cattle? 26 Three possible ways to protect an entitlement Property rule / injunctive relief Violation of my entitlement is punished as a crime Injunction: court order clarifying a right and specifically barring any future violation 27 Three possible ways to protect an entitlement Property rule / injunctive relief Violation of my entitlement is punished as a crime Injunction: court order clarifying a right and specifically barring any future violation Liability rule / damages Damages are a payment to a victim to compensate for actual damage done Better when prior negotiation is impossible Inalienability 28 Comparing property/injunctive relief to liability/damages rule Injuree (person whose entitlement is violated) always prefers a property rule Injurer always prefers a damages rule Why? Punishment for violating a property rule is severe If the two sides need to negotiate to trade the right, injurer’s threat point is lower Even if both rules eventually lead to the same outcome, injurer may have to pay more 29 Comparing injunctive relief to damages – example E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Electric company E emits smoke, dirties the laundry at a laundromat L next door E earns profits of 1,000 Without smoke, L earns profits of 300 Smoke reduces L’s profits from 300 to 100 E could stop polluting at cost 500 L could prevent the damage at cost 100 30 First, we consider the non-cooperative outcomes E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Polluter’s Rights (no remedy) E earns 1,000 L installs filters, earns 300 – 100 = 200 Laundromat has right to damages E earns 1,000, pays damages of 200 800 L earns 100, gets damages of 200 300 Laundromat has right to injunction E installs scrubbers, earns 1,000 – 500 = 500 L earns 300 31 E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Noncooperative payoffs Polluter’s Rights Damages Injunction E payoff (non-coop) 1,000 800 500 L payoff (non-coop) 200 300 300 1,200 1,100 800 Combined payoff (non-coop) 32 What about with bargaining? Polluter’s Rights Damages E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Injunction E payoff (non-coop) 1,000 800 500 L payoff (non-coop) 200 300 300 Combined payoff (non-coop) 1,200 1,100 800 Gains from Coop 0 100 400 E payoff (coop) 1,000 800 + ½850 (100) 500 + ½ (400) 700 L payoff (coop) 200 300 + ½350 (100) 300 + ½ (400) 500 Combined 1,200 1,200 1,200 33 How do we choose between the rules? In this case… Polluter’s rights > damages > injunction when there is no bargaining All three equally efficient when there is bargaining Normative Hobbes: allocate rights efficiently to begin with Polluter’s rights in this case, no reason to believe this more generally Normative Coase: just work to lower transaction costs, let people negotiate when they need to So what do we do? 34 How do we choose between the rules? Injunctions are cheaper for court to implement No need to calculate exact amount of damage done Damages are more efficient when private bargaining fails Leads Calabresi and Melamed to the following conclusion: When transaction costs are high, a liability rule (damages) is more efficient When transaction costs are low, a property rule (injunctive relief) is more efficient 35 So that’s our answer: Calabresi and Melamed When transaction costs are high, a liability rule (damages) is more efficient When transaction costs are low, a property rule (injunctive relief) is more efficient Why are damages more efficient when bargaining fails? Under damages rule, injurer has two choices: prevent the damage, or pay cost afterwards Under injunction, injurer has only one choice: prevent the damage Injuree is compensated, so doesn’t matter to him So whichever is cheaper for injurer, is more efficient 36 High transaction costs damages Low transaction costs injunctive relief “Private bargaining is unlikely to succeed in disputes involving a large number of geographically dispersed strangers because communication costs are high, monitoring is costly, and strategic behavior is likely to occur. Large numbers of land owners are typically affected by nuisances, such as air pollution or the stench from a feedlot. In these cases, damages are the preferred remedy. On the other hand, property disputes generally involve a small number of parties who live near each other and can monitor each others’ behavior easily after reaching a deal; so injunctive relief is usually used in these cases.” (Cooter and Ulen) 37 A different view of the high-transaction-costs case… “When transaction costs preclude bargaining, the court should protect a right by an injunctive remedy if it knows which party values the right relatively more and it does not know how much either party values it absolutely. Conversely, the court should protect a right by a damages remedy if it knows how much one of the parties values the right absolutely and it does not know which party values it relatively more.” (Cooter and Ulen) 38 Low transaction costs injunctive relief Cheaper for the court to administer With low transaction costs, we expect parties to negotiate privately if the right is not assigned efficiently But… do they really? Ward Farnsworth (1999), Do Parties to Nuisance Cases Bargain After Judgment? A Glimpse Inside The Cathedral 20 nuisance cases: no bargaining after judgment “In almost every case the lawyers said that acrimony between the parties was an important obstacle to bargaining… Frequently the parties were not on speaking terms... …The second recurring obstacle involves the parties’ disinclination to think of the rights at stake… as readily commensurable with cash.” 39 Third remedy: inalienability Inalienability: when an entitlement is not transferable or saleable 40 what can be privately owned? what can an owner do? how are property rights established? what remedies are given? 41