THE IMPACT OF THE TRIO STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES PROGRAM AT

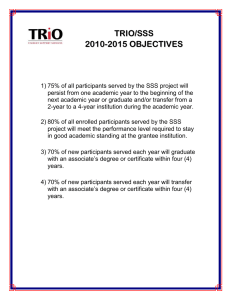

advertisement