Chapter – 5: Names, Bindings, Type Checking, and Scope Introduction

advertisement

Chapter – 5: Names, Bindings, Type Checking, and Scope

Introduction

• Imperative languages are abstractions of von Neumann

architecture: Memory (stores both instructions and data);

Processor (provides operations for modifying the contents of

the memory).

• Variables characterized by attributes (properties), most

important:

– Type (fundamental concept): to design, must consider

scope, lifetime, type checking, initialization, and type

compatibility.

Names (Identifier): string of characters used to identify some

entity in a program.

Name is a fundamental attribute of variables, labels, subprograms,

formal parameters, program constructs.

• Design issues for names:

– Maximum length? Are connector characters allowed?

– Are names case sensitive? Are special words reserved

words or keywords?

• Length

– If too short, they cannot be connotative.

– Language examples: FORTRAN I: maximum 6;

COBOL: maximum 30; FORTRAN 90 and ANSI C:

maximum 31; Ada and Java: no limit, and all are

significant; C++: no limit, but implementers often impose

one. Ada may impose limit on length up to 200

characters.

Impose limit in order to make the symbol table not too large,

simplify maintenance.

Names in most PLs have the same form: letter followed by a string

of letters, digits, and underscore.

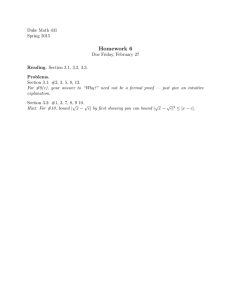

Ch5-1

• Connectors

– Pascal, Modula-2, and FORTRAN 77 don't allow; Others

do

• Case sensitivity

– Disadvantage: Detriment to readability (names that look

alike are different)

Worse in C++ and Java because predefined names are

mixed case (e.g. IndexOutOfBoundsException;

parseInt)

– C, C++, and Java names are case sensitive

• The names in other languages are not

• Special words (void, procedure, begin, end, if, else, int, char,

etc.)

– An aid to readability; used to delimit or separate

statement clauses

– A keyword is a word that is special only in certain

contexts, e.g., in Fortran (special words are keywords)

Real VarName (Real is a data type followed with a name,

therefore Real is a keyword), declarative statement.

Real = 3.4 (Real is a variable)[Real Apple Real=1.2]

– A reserved word is a special word that cannot be used as

a user-defined name.

– As a language design choice, reserved words are better

than keywords because the ability to redefine keywords

can be confusing (e.g. in Fortran: Integer Real

Real

Integer)

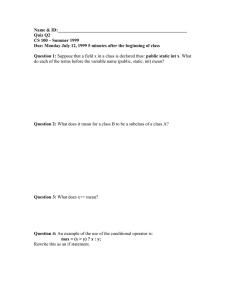

Variables

• A variable is an abstraction of a memory cell

• Variables can be characterized as a sextuple of attributes:

– Name, Address, Value, Type, Lifetime, Scope

Ch5-2

Variables Attributes

• Name - not all variables have them (e.g. of not having name

Explicit heap-dynamic variables).

• Explicit heap-dynamic variables: are nameless memory cells

that are allocated/deallocated (from/to) heap by explicit runtime instructions, referenced by pointer or reference variable.

Ex: C++

int *intnode; //creater pointer

intnode= new int; //create heap-dynamic variable

delete intnode;//deallocate heap-dynamic variable

• Address - the memory address with which it is associated

– A variable may have different addresses at different times

during execution (e.g. subprogram has a local variable

that is allocated from run-time stack. When the

subprogram is called, different calls may result in that

variable having different addresses).

– A variable may have different addresses at different

places in a program.

Ex:

program sum

Because these two variables are independent

sub1{ int x }

of each other, a reference to x in sub1 is

sub 2 { int x }

unrelated to a reference to x in sub2.

– If two variable names can be used to access the same

memory location, they are called aliases (suppose sum

and total variables are aliases, any change to total also

changes sum and vice versa).

– Aliases are created via pointers, reference variables, C

and C++ unions. Union type: type that store different

type values at different times during execution. (e.g.

consider a table of constants for a compiler which is used

to store constants found in a program. One field of each

table entry is for the value of the constant. Suppose

constants types are int, float, Boolean. It is convenient if

the same location (table field), could store a value of any

Ch5-3

of 3 types. Then all constant values can be addressed in

the same way, i.e. location type is union of 3 value types

it can store).

– Aliases are harmful to readability (program readers must

remember all of them).

• Type - determines the range of values of variables and the set

of operations that are defined for values of that type; in the

case of floating point, type also determines the precision.

• Value - the contents of the location with which the variable is

associated.

• Abstract memory cell - the physical cell or collection of cells

associated with a variable (float, although may occupy 4

physical bytes, we think as it occupying a single abstract

memory cell.

The Concept of Binding

• The l-value of a variable is its address; the r-value of a

variable is its value. To access the r-value, the l-value must be

determined 1st.

• A binding is an association, such as between an attribute and

an entity, or between an operation and a symbol

• Binding time is the time at which a binding takes place.

Possible Binding Times

• Language design time-- bind operator symbols to operations

(* is usually bound to multiplication operation at language

design time.

• Language implementation time-- bind floating point type to a

representation, bound int to a range of possible values.

• Compile time -- bind a variable to a type in C or Java.

• Load time -- bind a FORTRAN 77 variable to a memory cell

(or a C static variable).

• Link time-- a call to a library subprogram is bound to the

subprogram code.

• Runtime -- bind a nonstatic local variable to a memory cell.

Ch5-4

Ex: consider the C assignment statement count count 5;

Type of count is bound at compile time; set of possible values of

count is bound at compile design time,; meaning of operator

symbol (+) is bound at compiler design time after operands have

been determined; internal representation of literal 5 is bound at

compiler design time; the value of count is bound at execution time

with this statement.

Static and Dynamic Binding

• A binding is static if it first occurs before run time and

remains unchanged throughout program execution.

• A binding is dynamic if it first occurs during execution or can

change during execution of the program.

• Binding of a variable to a storage cell in a virtual memory

environment is complex, because the page or segment of the

address space in which the cell resides may be moved in and

out of memory many times during program execution. i.e.

variables are bound and unbound repeatedly.

Type Binding

• How is a type specified? When does the binding take place?

• If static, the type may be specified by either an explicit or an

implicit declaration.

Explicit/Implicit Declaration

• An explicit declaration is a program statement used for

declaring the types of variables

• An implicit declaration is a default mechanism for specifying

types of variables (the first appearance of the variable in the

program). Both declarations create static bindings to types.

• PL/1, FORTRAN, BASIC, and Perl provide implicit

declarations

– Advantage: writability

Ch5-5

– Disadvantage: reliability: because they prevent the

compiler from detecting some typographical and

programmers errors. (Less trouble with Perl, $, @, %).

– In Fortran, Implicit none (prevent accidentally

undeclared variables)

Dynamic Type Binding

• Dynamic Type Binding (JavaScript and PHP): variable type is

not specified by declaration nor spelling. But specified

through an assignment statement; e.g., in JavaScript, list = [2,

4.33, 6, 8]; regardless of previous type of list. It is now 1dimensional array of length 4. If the statement list = 17.3; is

followed, list become a scalar variable.

Advantage: flexibility (generic program units: whatever type

data is input will be acceptable, because variables can be bound

to correct type when data assigned to them).

Disadvantages: High cost (dynamic type checking done in runtime, and must use pure interpreter which takes more times);

less reliable, type error detection by the compiler is difficult.

Incorrect types of R.H.S of assignments are not detected as

errors; rather the type of L.H.S is changed to incorrect type. (e.g.

in JavaScript, suppose i, x are storing scalar numeric values, and

y storing an array. Suppose instead of writing i=x; we wrote

(due to keying error), i=y; no error is detected in this statement,

and i is changed to an array. But later on, the uses of i will

expect it to be a scalar, and correct results will be impossible.

•

Type Inferencing (ML, Miranda, and Haskell)

Rather than by assignment statement, types are determined from

the context of the reference. e.g. in ML, types of most

expressions can be determined without requiring the

programmer to specify the types of the variables.

Ex: fun circumf r 3.14159 * r * r; specifies a function

takes real and produces real. The types are inferred from the

type of the constant in the expression. Consider the function

Ch5-6

fun squarex x * x; ML determine type of both (parameters and

return value), from the operator *. Because it is an arithmetic

operator, the type of parameters and function are assumed

numeric. Default type of numeric in ML, is int. so it inferred the

type is int.

If square were called with real value, square(2.7), it will cause

an error. We could rewrite it fun squarex : real x * x; because

ML does not allow overloaded functions, this version could not

coexist with earlier int version.

• Storage Bindings & Lifetime

– Allocation - getting a cell from some pool of available

cells

– Deallocation - putting a cell back into the pool.

• The lifetime of a variable is the time during which it is bound

to a particular memory cell.

Categories of Variables by Lifetimes

• Static--bound to memory cells before execution begins and

remains bound to the same memory cell throughout execution,

e.g., all FORTRAN 77 variables, C static variables

– Advantages: efficiency (direct addressing), historysensitive subprogram support, i.e. having variables to

retain values between separate executions of the

subprogram (static bound).

– C&C++ allow including static specifier on a variable

definition in a function, making the variables static.

– Disadvantage: lack of flexibility (no recursion); storage

cannot be shared among variables (e.g. program has 2

subprograms, both require large arrays. suppose the two

subprograms are never active at the same time. If the

arrays are static, they cannot share the same storage for

their arrays).

Ch5-7

• Stack-dynamic--Storage bindings are created for variables

when their declaration statements are elaborated (take place

when execution reaches the code to which the declaration is

attached), but whose types are statically bound. Elaboration

occurs during run-time. Ex: variable declarations that appears

at the beginning of a Java method are elaborated when the

method is called; and the variables defined by those

declarations are deallocated when the method complete its

execution.

• Stack-dynamic variables are allocated from the run-time stack.

• Recursive subprograms require some form of dynamic local

storage, so that each active copy of the recursive subprogram

has its own version of local variables. These needs are met by

stack-dynamic variables. Even if there is no recursion, having

stack-dynamic local storage for subprograms make them share

the same memory space for their locals.

• If scalar, all attributes except address are statically bound

– local variables in C subprograms and Java methods. C#

are by default stack-dynamic. In Ada all non-heap

variables in subprograms are stack-dynamic

• Advantage: allows recursion; conserves storage

• Disadvantages:

– Run-time overhead of allocation and deallocation

– Subprograms cannot be history sensitive

– Inefficient references (indirect addressing), slower

access.

• Explicit heap-dynamic -- Allocated and deallocated by explicit

directives, specified by the programmer, which take effect

during execution. Heap is a collection of storage cells whose

organization is highly disorganized because of the

unpredictability of its use.

Ch5-8

• An explicit heap-dynamic variable has two variables

associated with it: a pointer or reference variable through

which the heap-dynamic variable can access, and the heapdynamic variable itself. Because an explicit heap-dynamic

variable is bound to a type at compile, it is static binding.

However, such variable is bound to storage at the time they

are created, which run-time.

• e.g. dynamic objects in C++ (via new and delete), all objects

in Java, are explicit heap-dynamic.

• Advantage: Explicit heap-dynamic provides for dynamic

storage management: dynamic structures (linked lists, trees)

that need to grow/shrink during execution, better build using

pointer or reference, and explicit heap-dynamic variables.

• Disadvantage: inefficient (cost of references to the variables;

complexity of storage management implementation), and

unreliable (pointers).

• Implicit heap-dynamic—are names that adapt to whatever use

they are asked to serve; allocation and deallocation caused by

assignment statements (i.e. bound to heap storage only when

they are assigned values).

• all variables in APL; all strings and arrays in Perl and

JavaScript

• Advantage: flexibility (allowing highly generic code to be

written)

• Disadvantages: Inefficient, because all attributes are dynamic

(run-time overhead). Loss of some error detection by

compiler. Have the same storage management problems as

explicit heap-dynamic.

Ch5-9

Type Checking

• Generalize the concept of operands and operators to include

subprograms and assignments, i.e. we think of subprograms as

operators whose operands are their parameters. The

assignment symbol will be thought of as a binary operator,

with its target variable and its expression being operands.

• Type checking is the activity of ensuring that the operands of

an operator are of compatible types.

• A compatible type is one that is either legal for the operator, or

is allowed under language rules to be implicitly converted, by

compiler- generated code ( or interpreter), to a legal type

– This automatic conversion is called a coercion, (int to

float).

• A type error is the application of an operator to an operand of

an inappropriate type, e.g. in original version of C, if an int

value was passed to a function that expected a float, a type

error would occur (because C compiler did not check

parameters types).

• If all bindings of variables to types are static, nearly all type

checking can be static

• If type bindings are dynamic, type checking must be dynamic

at run-time, is called dynamic type checking. JavaScript, PHP

(dynamic binding) allows only dynamic type checking.

• It is better to detect errors at compile-time than at run-time;

less costly. But static checking reduces flexibility.

• A programming language is strongly typed if type errors are

always detected. This requires that the type of all operands can

be determined either at compile-time or run-time.

Ch5-10

Strong Typing

• Advantage of strong typing: allows the detection of the

misuses of variables that result in type errors.

• Language examples:

– FORTRAN 95 is not: EQUIVALENCE of different

types, allows a variable of one type to refer to a value of

a different type. Pascal and Ada are not: variant records.

C and C++ are not: parameter type checking can be

avoided; unions are not type checked. Ada is, almost

(UNCHECKED CONVERSION is loophole).

(Java, C# is similar to Ada): nearly; types can be explicitly

cast, which could result in a type error.

• Coercion rules strongly affect strong typing--they can weaken

it considerably (C++ versus Ada), no casting in Ada. Ex:

suppose a program had int a, b; float d; now the

programmer meant to type a+b, but mistakenly typed a+d, the

error would not be detected by the compiler. The value of a is

coerced to float. So the strong typing is weakened by

coercion.

• Although Java has just half the assignment coercions of C++,

its strong typing is still far less effective than that of Ada.

Type Compatibility: Two variables being of compatible types, if

either one can have its value assigned to the other. Two different

types of compatibility.

Name Type Compatibility

• Name type compatibility means the two variables have

compatible types if they are in either the same declaration or

in declarations that use the same type name.

• Name type compatibility easy to implement but highly

restrictive:

Ch5-11

– Subranges of integer types are not compatible with

integer types. e.g. , consider the following Ada code:

type Indextype is 1..100; The variables count and index would not be

count : Integer;

compatible, i.e. count not be assigned to

index : Indextype;

index or vice versa.

– Formal parameters must be the same type as their

corresponding actual parameters (Pascal)

Structure Type Compatibility

• Structure type compatibility means that two variables have

compatible types if their types have identical structures.

• More flexible, but harder to implement.

• Under name type compatibility, only the two type names must

be compared to determine compatibility, while under

structured type, the entire structures of the two types must be

compared.

• Consider the problem of two structured types:

–Are two record types compatible if they are structurally the

same but use different field names?

–Are two array types compatible if they are the same except that

the subscripts are different?(e.g. [1..10] and [0..9])

–Are two enumeration types compatible if their components are

spelled differently?

–With structural type compatibility, you cannot differentiate

between types of the same structure, (e.g. different units of

speed, both float)

type kilometer Float;

mile Float;

Variables of these types considered

compatible under structure type

compatibility allowing to be mixed,

which is not desirable.

Ch5-12

C uses structure type compatibility for all types except struct and

union. Every struct and union declaration creates a new type that is

not compatible with any other. OOL (Java, C++, bring another kind

of type compatibility, object compatibility and its relationship to

inheritance.

Variable Attributes: Scope

• The scope of a variable is the range of statements over which

it is visible, i.e. can be referenced in that statement.

• The nonlocal variables of a program unit are those that are

visible but not declared there. A variable is local in a program

unit or block if it is declared there.

• The scope rules of a language determine how references to

names are associated with variables

Static Scope: the method of binding names to nonlocal variables

and the scope is statically determined, i.e. prior to execution.

• There are two categories of static-scoped languages: those in

which subprograms can be nested, which creates nested static

scopes (Ada, JavaScript, PHP); and those in which

subprograms cannot be nested (C-based languages). We

focuses on languages allow nested subprograms.

• To connect a name reference to a variable, you (or the

compiler) must find the declaration.

• Search process: search declarations, first locally, then in

increasingly larger enclosing scopes, until one is found for the

given name

• Enclosing static scopes (to a specific scope) are called its

static ancestors; the nearest static ancestor is called a static

parent.

Ch5-13

Consider the following Ada procedure

procedure Big is

x : Integer;

procedure sub1 is

Under static scoping, reference to x in

begin - - of sub1

sub1 is to x declared in Big. Why?

...x...

Because search for x begins in the

end; - - of sub1

procedure in which the reference

procedure sub2 is

occurs, sub1, but no declaration is

x : Integer;

begin - - of sub2

......

end; - - sub2

begin - - of Big

...

end; - - of Big

found. The search continues in static

parent of sub1, Big, where the

declaration is found.

• Variables can be hidden from a unit by having a "closer"

variable with the same name. Consider the following C++

method:

void sub {

int count ;

...

while ...{

int count ;

count ;

....

}

...

}

The reference to count in the while

loop is to that loop's local count. The

count of sub is hidden from the code

inside the while loop. In general, a

declaration for a variable effectively

hides any declaration of a variable

with the same name in a large

enclosing scope.

• C++ and Ada allow access to these "hidden" variables:

In Ada: unit.name in procedure Big, x declared in Big can be

accessed in sub1 by reference Big.x

Ch5-14

In C++: class_name::name local variable can hide global. Hidden

global can be accessed using (scope operator ::), e.g. if x is a global

hidden in a subprogram by local x, the global could be referenced

as ::x

Blocks

A method of creating static scopes inside program units--from

ALGOL 60, which allows a section of code to have its own local

variables whose scope, is minimized. Such variables are stackdynamic, so they have their storage allocated when the section is

entered and deallocated when the section is exited.

Examples: C and C++:

for (...) {

int index;

...

}

Allow any compound statement to have

declarations and thus define a new scope.

Compound statements are blocks.

Ada:

declare LCL : FLOAT;

begin

...

End

In Ada, blocks are specified with

declare clauses; compound statement

is delimited by begin and end

Scopes created by blocks are treated like those created by

subprograms. References to variables in a block that are not

declared there are connected to declarations by searching enclosing

scopes in order of increasing size.

C++ allows variable definitions to appear anywhere in functions.

When a definition appears at a position other than at the beginning

of a function, but not within a block, that variable's scope is from

Ch5-15

its definition statement to the end of function. for statement of

C++, Java, C#, allow variable definitions in their initialization

expressions. The scope is restricted to for construct.

Evaluation of Static Scoping

• Assume MAIN calls A and B

A calls C and D

B calls A and E

MAIN

MAIN

A

C

A

B

D

C

B

D

E

E

MAIN

A

C

MAIN

B

D

A

E

C

B

D

E

Static Scope Example

• Suppose the specification is changed so that D must now

access some data in B

Ch5-16

• Solutions:

Put D in B (but then C can no longer call it and D cannot access A's

variables).

Move the data from B that D needs to MAIN (but then all

procedures can access them), creates possibility of incorrect

accesses. Misspelled identifier in a procedure can be taken as a

reference to an identifier in some enclosing scope, instead of being

detected as an error. Furthermore, suppose the variable that is

moved to MAIN is named x, and x is needed by D and E. But

suppose that there is a variable named x declared in A. That would

hide the correct x from its original owner, D. Another problem,

moving x to MAIN is harm the readability, because it is far away

from its use.

• Overall: static scoping often encourages many globals than

necessary. One solution to static scoping problems is

encapsulation

Dynamic Scope (APL, SNOBOL4, early LISP, Perl, COMMON

LISP)

• Based on calling sequences of subprograms, not on their

spatial relationship to each other. Scope can be determined in

run-time.

• References to variables are connected to declarations by

searching back through the chain of subprogram calls that

forced execution to this point

Ch5-17

Scope Example

MAIN

- declaration of x

SUB1

- declaration of x ...

call SUB2

...

MAIN calls SUB1

SUB1 calls SUB2

SUB2 uses x

SUB2

...

- reference to x ...

...

call SUB1

…

Scope Example

• Static scoping: Reference to x is to MAIN's x

• Dynamic scoping: Reference to x is to SUB1's x

• Evaluation of Dynamic Scoping:

–Disadvantage (Problems): Local variables of a subprogram

are all visible to any other executing subprograms during the

execution time span of the subprogram. There is no way to

protect local variables from this accessibility. Dynamic

scoping result in less reliable program compared with static

scoping.

Poor readability, because the calling sequence of subprograms

must be known, inorder to determine the meaning of references

to non-local variables.

– Advantage: Convenience: parameters pass from one

subprogram to another are simply variables that are defined in

Ch5-18

the caller. None of these need to be passed in a dynamically

scoped language, because they are implicitly visible in the

called subprogram.

Dynamic scoping is not as widely used as static scoping.

Programs in static are easier to read, more reliable and execute

faster than equivalent programs in dynamic scoping language.

Scope and Lifetime

• Scope and lifetime are sometimes closely related, ex: a

variable declared in a Java method that contains no method

calls. The scope of such variable is from its declaration to the

end of the method. While its lifetime is the period of time

between entering execution stage and terminated. (Static scope

spatial concept vs. lifetime temporal concept), clearly not the

same but appear to be related. But sometimes are different

concepts. Consider a static variable in a C or C++ function, it

is statically bound to the scope of that function and also

statically bound to storage. So its scope is static and local to

the function, but its lifetime extends over entire execution of

the program of which it is a part.

• Scope and life are unrelated when subprogram call are

involved. Consider a C++ function

void printHeader() {

} / * end of printHeader * /

void compute(){

int sum;

printHeader();

} / * end of compute * /

Scope of sum is completely contained

within the compute function. It does not

extend to the body of the function

printHeader, although printHeader

executes in the midst of the execution of

compute. While lifetime of sum extends

over the time during which printHeader

executes. Whatever location allocated to

sum will stay during and after the

execution of printHeader.

Referencing Environments

• The referencing environment of a statement is the collection

of all names that are visible in the statement

Ch5-19

• In a static-scoped language, it is the local variables plus all of

the visible variables in all of the enclosing scopes.

• In Ada, the referencing environment of a statement includes

the local variables, plus all of the variables declared in the

procedures in which the statement is nested (excluding

variables in non local scopes that are hidden by declarations in

nearer procedures).

• Consider the following Ada skeletal program

procedure Exampleis

A, B : Integer;

procedure Sub1 is

X,Y : Integer;

begin of Sub1

end; of Sub1

procedure Sub2 is

X : Integer;

procedure Sub3 is

X : Integer;

begin of Sub3

end; of Sub3

begin of Sub2

end; of Sub2

begin of Example

end. of Example

Point

Referencing Environment

1

X and Y of Sub1, A and B of

Example

2

2

X of Sub3, (X of Sub2 is hidden), A

and B of Example

3

3

X of Sub2, A and B of Example

4

4

A and B of Example

1

• A subprogram is active if its execution has begun but has not

yet terminated

Ch5-20

• In a dynamic-scoped language, the referencing environment is

the local variables plus all visible variables in all active

subprograms that are currently active. Some variables in

active subprograms can be hidden from the referencing

environment. Recent subprogram activations can have

declarations for variables that hide variables with the same

names in previous subprogram activations.

• Consider the following program. Assume function calls are:

main calls sub2, sub2 calls sub1.

void sub1(){

int a,b;

} / * end of sub1* /

void sub2() {

int b, c;

sub1;

} / * end of sub2 * /

void main() {

int c, d;

sub2();

} / * end of main * /

1

Point Referencing Environment

1

a and b of sub1, c of sub2, d of

main, (c of main and b of sub2 are

hidden)

2

2

b and c of sub2, d of main, (c of

main is hidden)

3

3

c and d of main

Named Constants

• A named constant is a variable that is bound to a value only

when it is bound to storage (i.e. only once)

• Advantages: readability, reliability, and modifiability.

Readability use pi instead of 3.14159

• Used to parameterize programs. Ex: program process fixed

number of data values (100) usually uses constant (100) in

different places

• Consider Java segment:

Ch5-21

void example() {

int[] intList new int[100];

String[] strList new String[100 ];

for (index 0; index 100; index ) { }

for (index 0; index 100; index ) {...}

average sum/100;

}

• When program need to modify the size of data, we need to

find all the occurrences of (100) and change it to the needed

value. On large programs, it can be tedious and error-prone.

An easier and more reliable method is to use a named constant

as a program parameters, as in:

void example() {

final int len 100;

int[] intList new int[len];

String[] strList new String[len ];

for (index 0; index len; index ) { }

for (index 0; index len; index ) {...}

average sum/len;

}

• when length must be changed; only one line must be changed.

• The binding of values to named constants can be either static

(called manifest constants) or dynamic

• Languages:

– Static binding of values to named constants: FORTRAN

90: allows only constant expressions to be used as the

values of its named constants. These constant expressions

can contain previously declared named constants, and

Ch5-22

–

–

–

–

constant values, and operators (constant-valued

expressions).

Dynamic binding: Ada, C++, and Java: allow expressions

containing variables to be assigned to constants in the

declarations. Ex: C++ statement const int result 2 * width 1;

declared result to be integer named constant whose value

is the expression. Value of width must be visible when

result is allocated and bound to its value.

In Java, named constants are defined with final reserved

word.

C# has two kinds of named constants: const named

constants, which are implicitly static, are statically bound

to values. Readonly named constants, which are

dynamically bound to values.

Ada allows named constants of enumeration and

structured types.

Variable Initialization

• The binding of a variable to a value at the time it is bound to

storage is called initialization. If the variable is statically

bound to storage, binding and initialization occur before run

time. If the binding is dynamic, initialization is dynamic and

initial values can be any expression.

• Initialization is often done on the declaration statement, e.g.,

in Java: int sum = 0;

C++: char name[] " computer science" ;

Ch5-23