Critical care of the patient with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage

advertisement

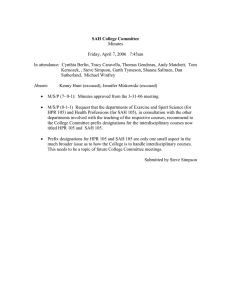

Critical care of the patient with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage William M. Coplin MD FCCM Associate Professor of Neurology and Neurological Surgery Medical Director, Neurotrauma & Critical Care Wayne State University Dr. Abdul-Monim Batiha Internal carotid artery Posterior communicating artery aneurysm Epidemiology of SAH • Incidence about 10/100,000/yr • Mean age of onset 51 years • 55% women – men predominate until age 50, then more women • Risk factors – cigarette smoking – hypertension – family history Case fatality rates for SAH • Population-based study in England with essentially complete case ascertainment – 24 hour mortality: 21% – 7 days: 37% – 30 days: 44% – Relative risk for patients over 60 years vs. younger = 2.95 Pobereskin JNNP 2001;70:340-3 Conditions associated with aneurysms • • • • • Aortic coarctation Polycystic kidney disease Fibromuscular dysplasia Moya moya disease Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Subarachnoid hemorrhage • Diagnostic approaches • Aneurysm management – surgical – endovascular • Critical care issues – rebleeding – neurogenic pulmonary edema – vasospasm and delayed ischemic damage – hydrocephalus – cerebral salt wasting – medical complications Diagnostic approach to SAH • • • • Wide range of symptoms and signs CT scanning Limited role of lumbar puncture Angiography – conventional vs. spiral CT vs. MRA – identification of multiple aneurysms – SAH without aneurysm Florid SAH with early hydrocephalus (ACLS text) More subtle subarachnoid hemorrhage interhemispheric fissure Sylvian fissure Flame and dot hemorrhages Subhyaloid hemorrhage Aneurysm management • Surgical – early surgery (first 3 days) becoming standard – large dose mannitol (electrolyte disturbances) – microsurgical technique • Endovascular – choice of cases for coiling – anesthesia or sedation issues • usually requires NMJ blockade Guglielmi detachable coil Basilar artery aneurysm before coiling Basilar artery aneurysm after coiling Complications of aneurysmal SAH • rebleeding • cerebral vasospasm • volume disturbances • osmolar disturbances • seizures • arrhythmias and other cardiovascular complications • CNS infections • other complications of critical illness “If it becomes at all doubtful, let me know, I will be just inside” 9:20 PM Captain Edward Smith to second officer Lightoller who then signed over to Murdoch at 10:00 PM 11:40 PM Critical care issues: rebleeding • Unsecured aneurysms: – 4% rebleed on day 0 – then 1.5%/day for next 13 days [27% for 2 weeks] • Antifibrinolytic therapy (e.g., aminocaproic acid) – may be useful between presentation and early surgery • Blood pressure management – labetalol, hydralazine, nicardipine • Analgesia • Minimal or no sedation to allow examination Critical care issues: vasospasm and delayed ischemic damage • Potential mechanisms – oxyhemoglobin/nitric oxide – endothelins • Diagnosis – – – – clinical transcranial Doppler flow velocity monitoring electrophysiologic radiologic Vasospasm in acute SAH Initial angiogram Repeat angiogram showing vasospasm (small arrows) Critical care issues: vasospasm and delayed ischemic damage • Prophylaxis – clot removal – volume repletion • prophylactic volume expansion not useful – nimodipine 60 mg q4h x 14 days • relative risk of stroke reduced by 0.69 (0.580.84). • nicardipine 0.075 mg/kg/hr is equivalent Critical care issues: vasospasm and delayed ischemic damage • Potential neuroprotective strategies – tirilizad mesylate is an effective neuroprotectant in SAH, approved in 13 countries but not the US – N-2-mercaptopropionyl glycine (N-2-MPG), approved for prevention of renal stones in patients with cysteinuria – AMPA antagonists (e.g., topiramate) – NMDA antagonists (e.g., ketamine) Critical care issues: vasospasm and delayed ischemic damage • Management – volume expansion – induced hypertension – cardiac output augmentation • dopamine or dobutamine • intra-aortic balloon pump – angioplasty – papaverine – erythropoetin? Frequency of medical complications after SAH (placebo arm of North American Nicardipine Trial) 350 300 250 200 total severe fatal 150 100 50 0 pu lm m on ar y et ab ol ic in fe G ct io us I ca rd ia c Solenski et al CCM 1995;23:1007-1017 Death by primary cause (87 deaths among 455 patients) 23% 22% 24% 7% 5% vasospasm medical complications rebleeding direct effect of SAH surgical complication other 19% Solenski et al CCM 1995;23:1007-1017 Extracerebral organ dysfunction and neurologic outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage 250 200 150 intact dysfunction failure 100 50 0 ol at m he c ia rd ca l ic og ry to tic pa he na re S ira sp re N C N=242 Gruber A et al.Crit Care Med 1999;27:505-14 Extracerebral organ dysfunction and neurologic outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 overall mortality rate with organ failure mortality rate with single organ failure mortality rate as part of multiple organ failure y ic og ol at m he c ia rd ca r to tic pa he l na re S ira sp re N C Gruber A et al.Crit Care Med 1999;27:505-14 Competing concerns Pulmonary complications after SAH 25 20 15 10 5 % (N=455) 0 r he ot y ar S D R A is as ct ele at ia on a m em eu ed pn on lm pu Solenski et al CCM 1995;23:1007-1017 Critical care issues: neurogenic pulmonary edema • Symptomatic pulmonary edema occurs in about 20% of SAH patients – detectable oxygenation abnormalities occur in 80% • Potential mechanisms: – hypersympathetic state – cardiogenic pulmonary edema – neurogenic pulmonary edema • Management Neurogenic pulmonary edema in SAH • radiographic pulmonary edema occurs in about 23% of SAH patients – up to 80% have elevated AaDO2 – a minority of cases are associated with documented LV dysfunction or iatrogenic volume overload • neurogenic pulmonary edema appears to be a consequence of the constriction of pulmonary venous sphincters – requires neural control; in experimental models, does not occur in denervated lung Neurogenic pulmonary edema after SAH PCWP=12 CI=4.2 Conditions associated with neurogenic pulmonary edema • Common: – subarachnoid hemorrhage – status epilepticus – severe head trauma – intracerebral hemorrhage • Rare: – – – – – brainstem infections medullary tumors multiple sclerosis spinal cord infarction increased ICP from a variety of causes Mechanisms of neurogenic pulmonary edema • hydrostatic: CNS disorder produces a hypersympathetic state, raising afterload and inducing diastolic dysfunction which cause hydrostatic pulmonary edema – 5/12 patients had low protein pulmonary edema • (Smith WS, Mathay MA. Chest 1997;111:1326-1333) – Consistent with either neurogenic or cardiogenic hypotheses Mechanisms of neurogenic pulmonary edema • neurogenic: contraction of postcapillary venular sphincters raises pulmonary capillary pressure without raising left atrial pressure – Abundant experimental evidence of neurogenic mechanism – Clinical evidence mostly inferred from low PCWP and early hypoxemia • structural: ‘fracture’ of pulmonary capillary endothelium Colice 1985 Managing neurogenic pulmonary edema • acute subarachnoid hemorrhage patients do not tolerate hypovolemia – volume depletion doubles the stroke and death rate due to vasospasm Managing neurogenic pulmonary edema • supplemental oxygen and CPAP or PEEP • place pulmonary artery catheter and, if there is coexisting cardiogenic edema, lower the wedge pressure to ~ 18 mmHg – echocardiography may be useful to determine whether cardiac dysfunction is also present • NPE usually resolves in a few days Metabolic complications after SAH 30 25 20 15 10 % (N=455) 5 0 I D m ce e yt ly g er l ro ct p hy ele ia Solenski et al CCM 1995;23:1007-1017 Infectious problems in SAH patients • important to distinguish saccular aneurysms from mycotic (frequently post-bacteremic) aneurysms • postoperative infections – postoperative meningitis may be aseptic, but this is a diagnosis of exclusion – particularly a problem in the SAH patient because the hemorrhage itself causes meningeal reaction • complications of critical illness • complications of steroid use Infectious complications after SAH 30 25 20 15 % (N=455) 10 5 0 fever UTI sepsis other Solenski et al CCM 1995;23:1007-1017 Etiology of fever in SAH patients • Collected data on 75 consecutive SAH patients who had undergone clipping. • Complete data available for 52 patients. • 32 (61.5%) of the 52 patients had at least one fever (temp >38.3°C) – Total of 46 episodes – 22% of episodes had no diagnosable cause (“central’) • Fever was not associated with vasospasm – Nonsignificant trend toward inverse relationship, 2 = 2.33, p < 0.13 Bleck TP, Henson S. Crit Care Med 1992;20:S31 Etiology of fever in SAH patients 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 febrile episodes 0 'ce l' ra nt p t-o SV gy H ler al n ug dr tio ec nf ei lin tis gi in en ia m on rm eu pn s po Bleck TP, Henson S. Crit Care Med 1992;20:S31 Evidence-based medicine • a system of belief that stresses the need for prospectively collected, objective evidence of everything except its own utility Bleck TP BMJ 2000;321:239 Real evidence-based rating scale • class 0: things I believe – class 0a: things I believe despite the available data • • • • • class 1: RCCTs that agree with what I believe class 2: other prospective data class 3: expert opinion class 4: RCCTs that don’t agree with what I believe class 5: what you believe that I don’t Bleck TP BMJ 2000;321:239 Seizures in SAH patients • about 6% of patients suffer a seizure at the time of the hemorrhage – distinction between a convulsion and decerebrate posturing may be difficult • postoperative seizures occur in about 1.5% of patients despite anticonvulsant prophylaxis • remember to consider other causes of seizures (e.g., alcohol withdrawal) Seizures in SAH patients • patients developing delayed ischemia may seize following reperfusion by angioplasty • late seizures occur in about 3% of patients Seizure management in SAH • seizures in patients with unsecured aneurysms may result in rebleeding, so prophylaxis (typically phenytoin) is commonly given • even a single seizure usually prompts a CT scan to look for a change in the intracranial pathology – additional phenytoin is frequently given to raise the serum concentration to 20+ ug/mL • lorazepam to abort serial seizures or status epilepticus DVT in the SAH patient • even after the aneurysm is secured, there is probably a risk of ICH in postoperative patients for 3 -5 days – therefore, we usually place IVC filters for DVTs • we also use IVC filters for unsecured aneurysm patients – angioplasty patients can probably be anticoagulated Nutrition in the SAH patient • no useful clinical trials available • hyperglycemia may worsen the outcome of delayed ischemia • ketosis appears to protect against cerebral ischemic damage in experimental models • if patients are not fully fed during the period of vasospasm risk, trophic feeding may be useful, and GI bleeding prophylaxis should be given Critical care issues: hydrocephalus • Diagnosis – clinical – radiologic • Management – ventriculostomy • infection reduction – shunting Hydrocephalus after SAH Critical care issues: other medical complications • Cardiac (almost 100% have abnormal ECG) – QT prolongation and torsade de pointes – left ventricular failure • Pulmonary – pneumonia – ARDS – pulmonary embolism (2% DVT, 1% PE) • Gastrointestinal – gastrointestinal bleeding (4% overall, 83% of fatal SAH) What about steroids? SAH prognosis • Sudden death prior to medical attention in about 20% • Of the remainder, with early surgery – 58% regained premorbid level of function • as high as 67% in some centers – 9% moderately disabled – 2% vegetative – 26% dead