Document 17539649

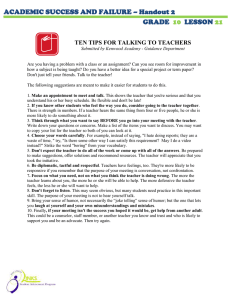

advertisement