RETENTION: CURRENT RESEARCH AND BEST PRACTICES A Project

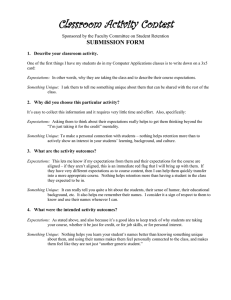

advertisement