GENDER AWARENESS AND PREPARATION IN CALIFORNIA TEACHING CREDENTIAL PROGRAMS Rachael Eliza Browne

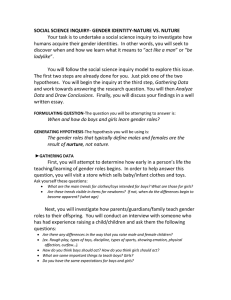

advertisement