Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

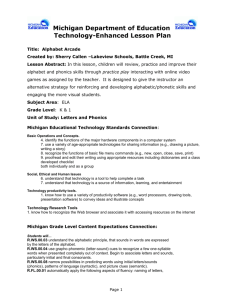

advertisement