THE EFFECT OF EXTERNAL FOCUS CUE INSTRUCTION Rhonda M. Mohr

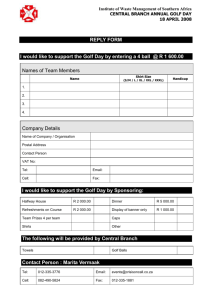

advertisement