THE DAWN OF EVE AND THE ETIOLOGY OF MYTH

advertisement

THE DAWN OF EVE AND THE ETIOLOGY OF MYTH

Iris Francine Putman

B.A., University of Texas at San Antonio, 2002

THESIS

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

LIBERAL ARTS

at

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO

FALL

2009

THE DAWN OF EVE AND THE ETIOLOGY OF MYTH

A Thesis

by

Iris Francine Putman

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Jeffrey Brodd

__________________________________, Second Reader

Dr. Bradley Nystrom

____________________________

Date

ii

Student: Iris Francine Putman

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Dr. Jeffrey Brodd

Department of Liberal Arts Master's Program

iii

___________________

Date

Abstract

of

THE DAWN OF EVE AND THE ETIOLOGY OF MYTH

by

Iris Francine Putman

In an attempt to clarify some of the mystery associated with the story of creation,

I offer a hermeneutic approach to the first four chapters of the book of Genesis. The

complexities of the scripture's meaning can never be wholly comprised through a literal

reading of the text. Much of its message is conveyed through symbolism, allegory, and

metaphor. Therefore, a close examination of the ancient Hebrew language is necessary in

order to approach a more accurate interpretation. Moreover, identifying the intersection

between ancient history (here, the history of ancient Mesopotamia) and biblical

history/literature remains paramount.

This interpretation makes use of various biblical translations, works by

theologians, and works and translations of myths from original languages by historians of

ancient Assyria, Sumeria, and Babylonia. The story of creation is rich and offers ideas

regarding relationship in all its forms, moral freedom, equality between the sexes, and

human value, as well as exhortations against the exploitation of the natural world and the

advent of civilization.

______________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Jeffrey Brodd

_______________________

Date

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................... vi

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION........................………………………………………………....1

2. IN THE VERY BEGINNING ................................................................................ 4

3. AN ANCIENT ATTEMPT AT PRE-HISTORY ................................................. 12

4. WOMAN: A DIVINE IMAGE ............................................................................. 20

5. CHOICE AND THE CURSE............................................................................... .27

6. EVE, THE SERPENT, THE CITY, AND MYTH............................................... .35

7. A NEW GENRE OF HEROES..............................................................................56

8.

CONCLUSION.....................................................................................................86

Work Cited....................................................................................................................92

v

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Page

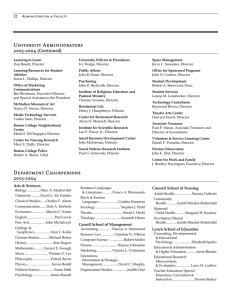

1. Illustration 1 Map of Ancient Mesopotamia………..…………………….………91

Saggs H.W.F. Babylonians: Peoples of the Past, 180.

vi

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Throughout my academic career in Humanities and Religious Studies, certain

philosophies, opinions, and ideas have weighed heavily on my mind, but none as heavy

as some of the opinions set forth by the Early Church Fathers. For example, the “doctrine

of the inferiority of women,” the idea that “religion” was divinely ordained, and the idea

that “Church,” as an institution is biblically based--these notions, whether a believer or

not, affect our lives as we live in a culture indelibly shaped by interpretations such as

these--interpretations that have also strongly directed the course of our world. As I began

investigating these issues, I found no biblical support for such propaganda. Moreover,

since many of the theological arguments centered around the story of creation, I too

decided to start at the beginning.

In this proposition, I offer a hermeneutic approach to the first four chapters of the

book of Genesis. The book of Genesis captures the essence of the Bible as a whole. The

first four chapters set the stage and define more distinctively all that follows. However,

the complexities of the scripture's meaning can never be wholly comprised through a

literal reading of the text. Much of its message is conveyed through symbolism, allegory,

and metaphor; therefore, a close examination of the ancient Hebrew language is

necessary in order to approach a more accurate reading of the text. Moreover, identifying

the intersection between ancient history (here, the history of ancient Mesopotamia) and

biblical history/literature remains paramount.

2

Using various biblical translations, works by biblical scholars, and works and

mythological translations by historians of antiquity I offer some further considerations.

The story of creation is rich and offers ideas regarding relationship in all its forms, moral

freedom, equality among the sexes, and human value, as well as exhortations against

exploitation of the natural world and the advent of civilization. Each of the chapters

address these issues in detail.

Chapter 2 introduces the creative character of the God of the proto-Hebrews and

his pre-existent nature in that it is pertinent in understanding the rest of the story. In

addition, I suggest that to improve fluidity and comprehension of the reading, J's account

must precede that of P. Chapter 3 defines the redactor's attempt at documenting prehistory by elucidating life within the garden. Here, the reader witnesses a primeval era

delineated by a simple way of life, worship, and respect for nature and the divine. In this

chapter, I use what I prefer to identify as “non-religion” to describe a life devoid of

civilization, technology, or man-made religion. Chapter 4 highlights the equality between

the sexes--both males and females as equally created in the image of God. Chapter 5

focuses on the freedom of choice (Eve), temptation (serpent), disobedience, and

expulsion. Chapter 6 gives meaning to the more specific symbolism associated with Eve

and the serpent and underscores the point of intersection between the two characters. This

point of intersection foreshadows the advent of civilization and technology which comes

to fruition through the line of Adam and Eve's son Cain. Moreover, since the conflict

between Cain and Abel arrives in the context of worship, the redactor implies that the

greatest conflict will come from man-made religion (polytheism). Chapter 7 provides a

3

long description of the character of biblical heroes. Because God “made them male and

female” in his image, both Judith and David are analyzed. Since the expulsion prevents

reentry into Eden, Judith and David provide examples of reclamation of creation--the

original intent of life within the garden. They understand the necessary pattern of conduct

and possess an intense understanding of the natural world and the way God works within

it. Judith and David provide examples of maintaining a relationship with God, even under

the influences of popular belief. Chapter 8 summarizes my analysis in total.

In my work I make the assumption that most, if not all, of my readers are at least

familiar with the Genesis account of creation. Moreover, because the text underscores

important truths about the human predicament that still reverberate today, I have chosen

to write in the present tense. Where I synchronize more closely with scholarly consensus

is in my description of the Hebrew God and Eve's link with civilization. The rest of my

interpretation offers further considerations especially in regard to the symbolism

associated with the serpent, Eve's meaning and placement in the story, the platform of the

conflict between Cain and Abel, and Eve's association with myth.

My desire in this endeavor is a discourse unadulterated and fresh. A discourse

arrived upon merely through the language of the text. I experienced difficulty finding

sources that did not present interpretations acquired through a patriarchal lens. However,

the most challenging aspect of my research was expressing with words the abstruse,

ambiguous concepts that form the bulk of the text. In this light, I have actively engaged

the text to offer some new possibilities regarding the Genesis creation story, a living

experience that reflects our lives even today.

4

Chapter 2

IN THE VERY BEGINNING

The stories of Genesis possess a timeless quality as they address the abstruse

regions of the soul that, through irresistible fascination, perpetually beckon for

understanding. Thus, in an attempt to explore origins, Genesis is an obvious staging

point. Genesis is a story of beginnings: the beginning of the universe, the beginning of

the people of Israel, the beginning of the human race and civilization, and the beginning

of monotheism. However, this exploration does not provide the kind of God and

worldview that conventional religion dictates. This exploration seeks to clarify some of

the mystery associated with the story of creation, Eve and her meaning and placement

within the story, her visitation by the serpent and the correlation to the etiology of myth.

The analysis here does not focus on the creational aspects in general (light, sky,

vegetation, etc.), but attributes associated with the divine-human relationship. The first

four chapters set the stage for the rest that follows.

Genesis, chapter one, expounds on the origins of earth, sky, vegetation, living

creatures, and human beings, as well as the Sabbath. Chapter two recounts the beginning

of human life and culture as well as the first transgression; chapter three focuses on

judgment, curse, and expulsion; and chapter four on sin, hatred and murder, as well as

cities and crafts. The initiating verse of the story assumes universal belief in a God that

needs no introduction. He has no family, no genealogy and his creative acts need no

sexual intercourse or violence, but are effortless and merely spoken into existence.

Understanding this creative character of the God of the proto-Hebrews is paramount to

5

the rest of the story. Here, the Hebrew verb bara' (created) whose sole subject is God,

encompasses all aspects of God including those that manifest themselves in the New

Testament; for example salvation, Wisdom, the Word, and Jesus--all then being present

“in the beginning” (Genesis 1:21, see note). According to Colossians the redactor

professes, “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him

all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether

thrones or dominions or rulers or powers--all things have been created through him and

for him. He himself is before all things and in him all things hold together” (Col 1:15-17).

The power in this statement asserts itself in the preposition “for him.” Not only does this

statement elaborate on the existence of pre-creation activities, it testifies to the Son's

preexistence and establishes that it is God's creation. He can act within it and do with it as

he so desires. (Herein, perhaps, lies the challenge of faith).

Along these lines, Karen Armstrong author of In the Beginning, lends perspective

to the Hebrew creation story:

P uses the formal divine title 'Elohim,' a term that sums up everything that the

divine can mean for humanity . . . Most of the Near Eastern deities had parents

and complex biographies that distinguished them from one another, but P

introduces his Elohim without telling us anything about his origins or past history

in primordial time. The pagan world found the timeless world of the gods a source

of inspiration and spirituality. Not so P, who ignores God's prior existence. As far

as he is concerned, his God's first significant act is to create the universe. Again,

the very notion of a wholly omnipotent deity was a new departure. All gods in the

6

Near East had to contend with other divine rivals. None had a monopoly of

power. It was a belief that expressed the tragic realism of the pagan vision, which

recognized life's complexity and could not admit the luxury of a final solution.

Pagans could not imagine a deity that could set all things to rights. P's claim that

his god can provide the only solution to life's ills is daring; his strict

monotheism is also a new departure in Israel, since hitherto most Israelites had

recognized the existence of other gods.

(10-11)

Armstrong is accurate in her assessment as the discussion of myth below will portray;

however, this monopoly of power transcends the visible lines of the story. The phrase “in

the beginning” suggests an existence of something before the creation--the principle

elements, the prime substance, the abode of the divine. The Hebrew word for

“beginning,” taken from the translations of James Strong in The Strongest Strong's

Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, is rē'ṧît which defines “what is first,” “firstfruits,”

“principle thing” (1564). In order to better grasp this concept it is helpful to examine

John's description of creation. John states: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word

was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things

came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being” (John 1:13). The Greek word for beginning here is archē, which envelops the same meaning as

found in Genesis but with broader explanation: “beginning,” “origins,” “first,” “ruler,”

“power,” “position of authority,” and “domain” (Strong 1595).

The two terms taken as a whole give meaning to formless matter and the darkness

that covered it. Like John here, Proverbs 8:22-31 suggests God's pre-existent nature and

7

his activity “before the beginning of his work” where he created Wisdom and the Word

to share his elemental abode with him (Prov 8: 22). Moreover, John's inclusion of Logos,

not simply the spoken word as in God's creative vehicle, but the Logos, in Greek thought

“the divine principle of reason that gives order to the universe and links the human mind

to the mind of God” (John 1:1, see note). Perhaps here, several other implications present

themselves: 1) an inward intention underlying the act of speech: to give order and reason

to the divine act, and to set a standard and a time limit to the divine purpose; and 2) to

offer the possibility of one language, an initial form of communication between the

divine and his human creation.

Thus, the intrinsic link between God and nature plays itself out even to the end of

the story, perhaps then, Armstrong's final solution. God's relationship to the world

involves both transcendence and immanence--his work in the world is never finished.

Revelation 21:1-2 states, “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven

and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the

new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God . . .” God then is seen as creatordestroyer-re-creator in what might be viewed as the circularity of God (a completion of

the cycles of his nature). Throughout the Bible, the Hebrew God uses the natural

elements to bless and to curse, to destroy and to rebuild. Therefore, in addition to the

book of Revelation, Old and New Testament alike attest to the un-creative/destroyer

nature of God and the earthly elements (Isa 34:4; Eze 38:20; Nahum 1:5; 2Peter 3:10).

Paul even warns his readers in Galatians 4 that the “elemental spirits,” or more

8

specifically, stoicheia, will not last forever. Stoicheia addresses basic principles; elements

of nature; elementary truths: elements, rudiments, truths (Strong 1644).

Here, Paul's discourse denounces attachment to a number of basic principles as

they were not created to last forever: 1) rudiments or first principles or elements: earth,

air, fire and water. In Paul's time these were seen as basic elements that control human

destiny (Gen 4, see note 4:1-7), 2) “elemental milk:” Milk and solid food commonly

symbolize levels of teaching. Those who live on milk alone never advance past their

elementary instruction, and perhaps will not ever advance to the word of righteousness,

or ethics (defined well in Heb 5:12-13), 3) demonic powers that oppress humankind:

philosophy, empty deceit, false teaching, human tradition, ritual, ceremony, festivals, and

the Law, and 4) a return to old ways: paganism/Judaism (Gal 4:1-20). Therefore, no

reality independent of God is a threat to creation, not observations of pre-existent chaos

or human device or wickedness. It is God who chooses to destroy or preserve.

Understanding this aspect of the Hebrew God lends perspective to further reading.

Moreover, this intrinsic link between God and nature reveals order and purpose, and a

delimitation within a set of prescribed divine boundaries that foreshadow future

behavioral expectations between God and his creatures, and underscores the disruption to

divine boundaries generated through human creation.

Terrence E. Fretheim, commentator on Genesis in The New Interpreter's Bible

asserts, “Many scholars consider the opening two chapters of Genesis as two creation

stories, assigning 1:1-2:4a to the Preistly writer and 2:4b-25 to the Yahwist. Moreover,

considerable effort has been expended in comparing and contrasting them. Newer

9

approaches to biblical texts, however, have raised anew the question of the shape of the

present form of the text. While the two accounts certainly have different origins and

transmission histories, they have also been brought together in a coherent way by a

redactor” (I : 340). Therefore, when reading Genesis, the fluidity and functionality of the

book are enhanced when the creation stories of P and J are viewed not as two separate

stories, but as two parts of the same story. Along these lines, it is necessary for J's

account to precede that of P.

Genesis 2:4b reads, “In the day that the Lord God made the earth and the heavens,

when no plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up-for the Lord God had not caused it to rain upon the earth and there was no one to till the

ground.”1 The timing indicated in this verse “in the day that,” or more precisely, at the

same time as, places the creation of Eden and its inhabitants on Day One of the six days

of creation. Day, or yôm, defines daytime (in contrast to night); by extension an indefinite

period of time, an era with a certain characteristic, for example “the day of the Lord” and

the prophetic “on that day” (Strong 1580). Here, “in the day that” places the creation of

Eden and its inhabitants on the first day of creation in all of its simplicity and indicates an

era that establishes a quintessential paradigm for living. Moreover, yôm represents the

spiritual potentials of living in communion with the divine: “continuance,” “everlasting,”

“sabbath,” and “prolonged life” (Strong 1580). This concept is solidified through the

author's use of YHWH (Yahweh), which in addition, enhances the creative element.

1 This verse presents an obvious break in its subject and format: Genesis 2:4a states: “These are the

generations of the heavens and earth when they were created; Genesis 2:4b states: “In the day that the

Lord God made the earth and the heavens.” The latter is of concern here.

10

J's use of Yahweh serves as a divine introduction to the God of a chosen people.

Here, Yahweh is not one god among many, but is the Creator and Ruler of the heaven

and earth. The name pictures God as the one who exists and causes to exist, the one who

is worthy of the complete homage of his human creation. The use of this very ancient and

intensely personal name denotes the creational purpose of an intensely personal

relationship with the whole of creation (Strong 1714, 3068). Moreover, the use of

Yahweh captures this creative essence best through the eternal nature of its association:

He who is (I am) or He who causes to be. God reveals his name as “I am who I am,” his

eternal covenant name that implies self-existence and saving presence (Ex 3:14-17); in

addition, the name embodies both the masculine and the feminine: Y and W are

masculine, and H and H are feminine (Strong 1816), which then points directly to the

creation of the first male and female . Thus, the androgynous traits of God are expressed

through the creation of his human counterparts. The shift in focus from “heaven and

earth” to “earth and heaven” indicates this point of emphasis--the capacity for personal

relations with humankind is included in the nature of the Deity.

Moreover, the use of language indicates an archetypal identity. In contrast to

Genesis 1:27 which uses 'ādām to represent humankind (male and female alike), Genesis

2 uses 'ādām as a proper noun to represent Adam, the first half of the divine couple

(Strong 1468). Timothy supports this as he states, “For Adam was formed first, then Eve .

. .” (1Timothy 2:13). Adam and Eve represent an original state of living, worship,

relationship, and contravention. In addition, placing J's account first is necessary because

it foreshadows the shaping of human destiny through focus on the people of Israel (hand

11

picked or formed by the hand of God), corruption of the interdependent relationship

between the humans and the divine, and the cause of the corruption as symbolized

through the temptation of Eve. The benefit of this reading is multifaceted.

First, it is the redactor's attempt at pre-history. Second, the story offers an

explanation of the origin of the institution of marriage and the intended equality between

the sexes. Third, it explains the existence of people and institutions (tribes, villages,

religions) outside of Eden after the expulsion and the point of supply for Cain's wife; and

last, Eve's correlation to the etiology of myth. Each will be taken in order.

12

Chapter 3

AN ANCIENT ATTEMPT AT PRE-HISTORY

The pre-history of Genesis spans Chapters 1-11 beginning with creation and

progressing through the early generations of humanity, ending in Mesopotamia. “These

texts tell a story of the past, more particular, a story of beginnings. They speak, not

simply of the general human condition, but also of the beginnings of life. This is not to

say that the material is historical in any modern sense, nor does it necessarily make any

historical judgments. Rather these narratives offer Israel's own understanding,” maintains

Fretheim (I : 336). J's rendition indicates Semitic origins beyond Israel's experience--a

beginning for the first monotheists--that form the link between a primeval era and later

developments: civilization, religion, language, script, polytheism, and kingship.

In addition, the first chapter of Genesis establishes that nature is God's language

for communicating with humankind: “and God said,” “and God made,” “and God

separated.” God controls, leads, and punishes with natural forces: He creates from dust

(Genesis 2), and destroys with natural disasters (Exodus). Job and Isaiah both testify that

God is the power behind nature whose ways cannot be questioned. This belief

corresponds with Paul's statement, “Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power

and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the

things he has made. So they are without excuse” (Romans 1: 20). Nature serves as a

universal language--any to whom God speaks understands.2 This idea is reinforced by

God “walking” in the garden following the transgression of Adam and Eve. Walk or

2 Compare to the confusion of language at the Tower of Babel.

13

hālak defines movement by extension: to walk as a lifestyle, or pattern of conduct

(Strong 1493). The weight here is twofold: 1) God maintains his conduct in the

relationship with Adam and Eve, and 2) it foreshadows Adam and Eve's breach of

conduct and expulsion through the fashioning of the fig leaves to hide their shame.

Speech and action are inseparable--good or evil. Hence, the will of God is the supreme

“good” because it is his will and he is God (“for him”). Humankind's safety and welfare

depend upon obedience to this will. In contrast, “evil” exists as an energy or compulsion

resident in human nature that the serpent arouses to activity. Any interruption in the

divine-human relationship results in the termination of paradise and living life in the

shadow of a curse.

Throughout the chapters regarding pre-history, in particular this focus on the first

four chapters, issues of relationship dominate the text from every conceivable

perspective. Most basic are the relationships between God and the creatures, especially

humans. The recurrent litany that all is created “good” serves as a warning signal

regarding God's creative work and the divine intention associated with the creation. The

appearance of disobedience/human sin, while it does not obliterate the divine-human

relationship or the important role humans play in the divine economy, has nonetheless

brought “deep and pervasive ill effects upon all relationships (human-God, human-human

at individual, familial, and national levels; human-non-human) and dramatically portrays

the need for reclamation of creation” (I : 337). Thus, the movement back and forth

between the first man and humankind, Adam and 'ādām, suggests an equitable link

between the prototype and the rest of humanity. This equitable balance among all human

14

creatures, especially between the sexes, is demonstrated at the naming of woman. The

equal partnership between man and woman is expressed by Adam renaming himself ish

(man/human being) and his new partner ishshah (woman) (Genesis 2:23, see note). Then,

the more specific naming of woman as Eve links woman to living life in a particular way

(Genesis 3:20). Therefore, Adam becomes “Every human” and woman becomes ḥawwâ,

or life, whose roles play out within or against their natural landscape (Strong 1499). Yet

there is a particular etiology associated with Adam. He is the progenitor of natural

worship, or more precisely non-religion, where he and his wife become the first

missionaries post-expulsion.

“In both P and J the unique relationship of mankind to God is shared by man and

woman. P expresses this most strikingly, but J conveys the same idea by representing

man as unable to find companionship among the animals and as finding it in her who was

made of his bone and flesh,” asserts Millar Burrows in his book An Outline of Biblical

Theology (142).3 The divine reflection as incomplete without woman is found in the “not

good” of man being alone. However, at this point God solicits assistance from Adam in

the continuation of the creation process. God creates the animals from the same dust as he

did Adam and Adam names each one. Fretheim expounds on the symbiosis of this

relationship: “God acts as name giver in vv. 5-10; God names the day, the night, the sky,

the earth, and the seas. God's naming stands parallel to, but does not overlap, the human

naming in 2:19-20.” He continues, “The act of creation constitutes, thus, no simple

3 There are perhaps etiological concerns, wherein origins (and/or prohibitions) are rooted in the very

distant past: dietary regulations (1:29-30; 2:16), prohibitions against bestiality (2:20), origin of fertility

worship as exemplified through Eve's self-aggrandizement (4:1), origins of various cultural activities

(4:20-22).

15

punctiliar act, but also involves a process of action and interaction with what has been

created. In this process, naming entails knowledge of and relationship with the thing

named” (I : 344).

This relationship extends to the earth itself (adamah), the raw material of God's

creative outlet, and is alluded to in verse five as there was “ no one to till it [the ground]

and keep it.” Fretheim suggests, “This image [deity as potter] reveals a God who focuses

closely on the object to be created and takes painstaking care to shape each one into

something useful and beautiful. At the same time the potter's work remains very much

bound to the earth and bears essential marks of the environment from which it derives” (I

: 349). Therefore Adam's relationship to God, the earth, and the animals are to bear the

same essential marks.

The Hebrew term 'ābad (till) captures the essence of this relationship well as it

suggests much more than mere gardening: 1) to work, serve, labor, do; to minister, work

in ministry; 2) to be plowed, to be cultivated; 3) to cause to serve, to worship [a god]

(Strong 1542). To “till” in this context suggests then that Adam is to serve and worship

God as well as serve and ŝāmar (keep, preserve) the garden in Eden he has been given to

inhabit (Strong 1576). It cannot mean work in this context as Adam's portion of the curse,

due to breach of divine law (Genesis 3:14-19), requires that “by the sweat of your face

you shall eat bread . . .” Here, the Hebrew noun zē'â, or sweat, refers to “heavy manual

labor” (Strong 1496) which provides a rigid contrast to “till” or worship making the

future curse effective. Moreover, God creates a paradise in which to live with water,

16

plants, food, and divine law. The only tasks left for Adam are to serve and worship the

creator, obey one divine law, and preserve the environment provided.

Consequently, the concept of non-religion, arrives through Adam. To better grasp

the concept of non-religion, it is best to first define what it is not:

It is not political in structure or form.

It is not civilized or technological.

In it exists no evil.

There exists a different notion of work which involves protection and care of

the earth and its inhabitants, in opposition to exploitation of the earth and its

inhabitants.

What exists then in the concept of non-religion is a harmony between God and

humankind, and humankind and the natural environment. Belief in God, here, is a natural

theology. God is never separate from the world and his worship is not separate from the

ordinary activities of everyday life.

Further support for this is found in the (divine couple's) state of being

“naked”('ārôm) without shame (Strong 1550), a condition which represents a

relationship with the divine absent of any barriers. The prohibition against eating of the

tree of the knowledge of good and evil is designed to maintain this barrier free

relationship. Knowledge of good is assumed as all that was created has been labeled as

such. However, even in the idyllic setting of the garden, evil has its potential. Evil or ra'

expresses that which is disagreeable to God as ethically evil (Strong 1567). In the words

of Burrows lies testimony to this relationship: “Another point to be kept in mind is that

17

the language of the Bible is not the language of philosophy or science; it is the language

of worship. It must be understood as poetry, not as factual description or analysis. Strictly

speaking, the Bible does not present a doctrine of God but a way of thinking about God.”

Along these lines he continues, “The clue to what may be expected of God is found in

what is best for man. It is from this point of view that biblical theism must be understood

and judged and accepted” (62-63).

Therefore, it is not surprising that parallels exist in the second half of the story

(Genesis 1:26-31) regarding 'ādām or humankind in the world at large. God continues to

allow for partnership in the creative process. The “let us make” extends not only to the

consultation of other divine beings but to human beings as well, “for they are created in

the image of one who chooses to create in a way that shares power with others” (I : 345).

This sharing of the creative process extends to the procreative capabilities of humankind

(and “every living creature”) and is fueled through the divine command to “be fruitful

and multiply, and fill the earth” (Genesis 1:28). Moreover, the seven day cycle of work

and rest designated for humankind replicates the creation process and the divine-human

sharing of it, and serves as a perpetual reminder that all are in a right relationship with the

Creator (Exodus 31:12).

Likewise, the absence of prohibition against eating from the tree of life (Genesis

2:16-17) magnifies a state of living that has movement and vigor that allows living to a

“whole age” and can be shared with a multitude (this applies to non-humans as well as

humans) (Strong 1499). Yahweh then is a God of relationship and his creation is the stage

upon which life plays out. However, it must be realized that life in this context is

18

inextricably linked to the judgments of God as “good” or “not good.” Evaluation remains

part of an on-going process within which improvement or injury are possible.

God gives the commands in the garden to worship (till) and protect (keep) and to

the rest of humanity to “have dominion” and “subdue.” Dominion or rādâ corresponds to

the command ŝāmar and indicates terms of care-giving and nurturing, not exploitation.

Human beings should relate to non-humans as God relates to them as reflections of his

image (I : 346). On the other hand, subdue offers sharp contrast to the garden story.

Subdue or kābaŝ, which means to subject or bring under control, provides a particular

latitude to life outside of Eden. Much like God's acceptance of the names Adam gave to

all the animals, God gives creation to the humans to decide how they will proceed within

it. Fretheim asserts, “This process [subduing] offers to the human beings the task of intracreational development, of bringing the world along to its fullest possible creational

potential . . . The future remains open to a number of possibilities in which the creaturely

activities will prove crucial for the development of the world” (I : 346).

The use of Elohim in this portion of the story reflects these “creaturely activities.”

In the Pentateuch the name Elohim connotes a general concept of God; that is, it portrays

God as the transcendent being, the creator of the universe. It does not connote the more

personal and palpable concepts inherent in the name Yahweh. Moreover, it can also be

applied to false gods as well as judges and kings. This foreshadows the interference in the

divine-human relationship that the advances in civilization and technology bring upon the

created order. As the human prototype demonstrates, all developments must be done in

the framework of worship, respect for the environment, and obedience to the divine. In

19

whatever manner humans decide to exercise their freedom of choice, God will work

around it as it is God who will ultimately evaluate the “good” and “not good” of the

developmental processes within his creation. In this light, Adam represents a series of

sharp contrasts: 1) nature and civilization, 2) God and humans, 3) worship and

disobedience, and 4) God as God and man as God. These contrasts come to fruition

through his wife, Eve.

20

Chapter 4

WOMAN: A DIVINE IMAGE

It is not surprising that Eve is the catalyst and pivotal point for the rest of the

story. The complexity of her character is both enlightening and disturbing. Eve's debut

initiates as the divinely hand-crafted partner made from Adam's own rib. Over the

centuries much has been hypothesized regarding woman's place in creation to which

Burrows sheds some light: “Undue stress by commentators on woman's subordination to

man in Genesis, chapter 2, has obscured the more basic point of their common elevation

above the animals” (142). In the Genesis story, it is God who decides that Adam needs a

helper (ēzer), not as an act of subordinating woman to man, but to share equally in the

ways of worship, care of creation, and the issues of life. Helper in no way implies

subordination. In the Old Testament, God is often called the helper of human beings,

actually, when ēzer is not referring to Eve, it appears seventeen times in reference to God

(Strong 542). For example, Psalms 121:1-2 suggests that the help for humankind comes

from the creator of the heavens and the earth. Therefore, a more precise reading would

suggest mutual assistance is necessary for a more complete way of living.

Adam is formed of dust which ties him unarguably to the earth, and Eve is made

of living tissue which ties her to life and the living--earth and life are inextricably linked

and meaningless without the other. Being made of a rib buttresses this concept in many

ways: 1) “One flesh” indicates a kinship which highlights mutuality and equality

(Genesis 29:14; 2 Sam 19:12-13), 2) Man is to leave the identity of his family and create

a new identity with his wife with a particular focus on the husband-wife relationship--

21

man and woman as an indissoluble unit of humankind from every perspective (I : 354), 3)

ribs come in pairs, 4) ribs are supporting structures, and 5) The relationship of husbands

and wives, as reflections of the divine, are to be prophetic of their personal relationship

with the divine.

Once again, it is the curse that causes misconceptions. Both Adam and Eve's

positions result from shared disobedience. Eve's portion of the curse for disobedience to

God (Genesis 3:16) is to experience pain in child birth and yet continue to desire her

husband, but be ruled by him as well. The verb māŝal, or “rule,” combines the idea of

dominion and rule. This maintains the idea of care of without exploitation; however, rule

means exactly what it implies. Fretheim elaborates: “The 'rule' of man over woman is part

and parcel of the judgment on the man as much as the woman. This writer understood

that patriarchy and related ills came as a consequence of sin rather than being the divine

intention” (I : 363). Therefore, to operate here or to create a “doctrine” of the inferiority

of women is to operate within the curse rather than within the original intentions for

human creation--both man and woman are equally created in the image of God. It may be

surprising to note that it is the Paul of the New Testament that sheds light on divinely

created equality between the sexes.

John Temple Bristow, author of What Paul Really Said About Women, explores

what he calls “the Ephesians 5 Syndrome” (32). His research is the focus in this section.

Bristow prefaces his argument with details examining the origin of the idea that women

are inferior to men and ends with Paul's explanation on the harmonious balance between

the sexes, especially within the marriage relationship. In his book, Bristow accuses Zeno,

22

Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, and the Essenes, in short, Greek philosophy, for the

legacy of disdain for women. Hellenization saw the spread of this mode of thinking. Even

though the Old Testament is replete with examples of capable and strong-willed women

such as Rahab, Ruth, Tamar, Deborah, Jael, and Judith, the rabbis of Judaism devalued

women in their teaching due to cultural biases that led to misinterpretations of scripture.

The tendency toward the Hellenization of Jewish thought was given formal sanction in

the writings of Philo, a Jewish scholar in Alexandria at the time of Christ. Philo sought to

harmonize the teachings of Plato and Aristotle and other Greek philosophers with the

teachings of the Old Testament. With this process came the imposition of Greek disdain

for women injected into his interpretation of the scripture. Later Christian scholars such

as Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Augustine, and Thomas Aquinas sought to

systematize Christian beliefs and harmonize them with Greek philosophy (1-29).

Therefore, if Paul wanted to Christianize the lands that Alexander had Hellenized,

he had to tear down the walls that Greek culture and philosophy had solidified between

people--including walls between men and women, and husbands and wives (Bristow 31).

Paul's model was radical to people of his day; however, it reflects the creators intentions

from the beginning. Bristow elaborates on “the Ephesians 5 syndrome” with particular

emphasis on verses 21-33 focusing specifically on what he labels as the key words:

“head,” “be subject to,” and “love.”

“The husband is head of the wife,” Paul explains, “as Christ is head of the

church” (Eph 5:23). To contrast the English word for head that provides two meanings

within the context of one word, such as literally the physical head of the body and

23

figuratively the leader of a body of people--the two meanings intertwined--Greek

provides two separate words to accommodate each separate meaning. One is archē,

which represents point of leadership, beginning, first (as in terms of importance and

power). Paul and other writers of the New Testament used this form of archē to designate

the head or leader of a group of people: “magistrate,” “chief,” “prince,” “ruler,” etc.

However, Paul did not make a pun out of archē and suggest that the husband is the archē

(or head) of his wife, implying then that Adam was the archē (or source) of Eve. Being

aware of the use and meaning of this word, Paul chose to describe the husband-wife

relationship quite differently (Bristow 35-36).

The word Paul chose to describe this relationship is kephale. This word does

mean “head” in reference to the part of the body, but also, it was used to mean

“foremost” in terms of position such as a capstone over a door or the cornerstone in a

foundation. Moreover, kephale as a military term denotes “one who leads,” not a

“general” or “captain,” but a kephale was one who went ahead of the troops as the first

one into battle. The validity of this interpretation, Bristow assures, relates to how these

two words are used in the Septuagint. In Hebrew, just as in English, one words means

both “physical head” and “ruler”--this Hebrew word is rosh. The lack of

interchangeability between archē and kephale is “carefully preserved” in the translations

of the Septuagint. When the seventy scholars who wrote the Septuagint came to the word

rosh they could have used either Greek word as they wished or one of the words all the

time; however, they were careful to note the context of the usage of rosh as to whether it

referred to “physical head” or “ruler of a group.” Whenever rosh meant “physical head”

24

or referred to a soldier leading others into battle with him, the translators used kephale.

However, when rosh meant “ruler” or “chief” or “leader” the translators used archē.

Bristow insists that “every time the distinction was carefully preserved” (36-37).

The second key word presents a broader scope of usage. In the above cited

scripture, the words “be subject to” appear three times: 1) believers (the Church) are to be

subject to one another, 2) wives are to be subject to their husbands, and 3) the Church is

to be subject to Christ (Eph 5:21-24). It must be noted, that if kephale does not indicate

rule or authority, then “be subject to” cannot refer to obedience. To be sure, Paul uses the

word for obedience (hupakouo) in regards to the behavior of children towards their

parents in Ephesians 6:1. If Paul intended to convey obedience, he would have used

hupakouo; however, this is not the case. When addressing wives, Paul used a form of the

Greek word hupotasso by writing in the imperative, middle voice, thus the word becomes

hupotassomai. By writing in the imperative mood, Paul was instructing wives, or rather

requesting that wives choose to behave in a particular way toward their husbands. (Here,

the subject of the verb is acting in a way that affects the subject). Therefore,

hupotassomai defines a request along the lines of “tend to the needs of” or “be supportive

of” rather than the awkward translation “be subject to.” Additionally, hupotassomai

serves as a military term referring to taking a position in the phalanx of the soldiers

without implication of rank or status, but as an equal sharing of the task for which the

soldiers are ordered (Bristow 38-41). The subtle analogy of Paul's words imply

something quite different than a Greek philosophical assumption portrays. Bristow writes

that the military usages implies that “ the husband is head when he sticks his neck out and

25

goes first into battle, and the wife is subject to her husband only by standing in formation

next to him and obeying the same orders as he” (44). Love is the solidifying factor.

Three times in this short passage husbands are instructed to love their wives. Of

the three kinds of love defined in Greek, erao, phileo, and agapao, it is the third listed to

which Paul refers. Indeed, agapao is the form of love most frequently used and

commanded in the New Testament as it is to reflect the love God has for his son and his

people (Strong 1748-1749). Bristow explains that erao denotes having sexual desire and

passion and was not commanded by Paul as it is not something that can be commanded.

Likewise, phileo denotes an emotional kind of love such as fondness, friendship, a deep

liking--a warmth that cannot be ordered into being. However, agapao is not attached to

emotion as much as attitude and action; therefore, it can be commanded. For example, the

greatest commandments use this word to instruct love of God, neighbors, and even one's

enemies. Bristow relays the “almost identical” link between agapao and hupotassomai as

involving giving up one's self-interest to serve and care for another (Bristow 41-42).

What then does Paul's model reveal?

Paul's model reveals that “wives are to hupotassomai their husbands; husbands

are to agapao their wives.” Paul described a husband as the head of the wife as Christ is

head of the church; therefore a husband is to nourish and sanctify his wife and even be

willing to die for her, and a wife is to be supportive of and responsive to the needs of her

husband and he is to (agapao) be responsive to her needs as well (Bristow 42-43). Thus,

it is not surprising that Paul quotes Genesis 2:24 emphasizing the “one flesh” of marital

union. Being formed first and out of the earth symbolizes that Adam is the foundation

26

(kephale) upon which Eve can stand. Eve's creation from the rib of Adam symbolizes that

she is his supporting structure (hupotassomai). Therefore, Paul's request for husbands to

love their wives as their own bodies is not surprising. Eve was formed out of the body of

her husband, so in loving her he demonstrates self-respect, and they are one flesh. Yet,

Eve offers more than support for her husband. She is the vehicle through which the

freedom of choice was first expressed.

27

Chapter 5

CHOICE AND THE CURSE

Chapter three initiates with a very brief introduction of the serpent: “Now the

serpent was more crafty than any other wild animal that the Lord God had made”

(Genesis 3:1a).4 Everett Fox, author of In the Beginning: A New English Rendition of the

Book of Genesis, suggests a successful link is made between the Garden of Eden and the

temptation through the use of the word crafty by “linking two identical-sounding words

in the Hebrew, arum (here, 'nude' and 'shrewd')” (15). This link foreshadows a change in

circumstance and relationship as the serpent stands as the disruptor of the paradisaical

balance. On one hand, nude represents a harmonious relationship with the divine devoid

of barrier and shame (Genesis 2:25); on the other hand, nude represents separation from

the divine, barrier, and shame (Genesis 3:10). In addition, the serpent brings to mind the

series of contrasts that have been at play since the beginning of the narrative: heaven and

earth, “good” and “not good” (with the potential for evil), life and death, knowledge and

choice.

The most important contrast established since the beginning of the story is the

contrast between “good” and “not good,” with steps taken to resolve all that was “not

good.” All other contrasts (and situations and people) fit quite neatly under these two

headings. God is good, the serpent not good and both are indicators within the rest of the

narrative. However, what astounds most is that God created the serpent as he did all other

4 There is an obvious break in subject and format: Genesis 3:1a reads, “Now the serpent was more crafty

than any other creature the Lord God had made;” Genesis 3:1b reads, “He said to the woman, Did God

say, 'You shall not eat from any tree in the garden?'”

28

earthly creatures. The woman's phlegmatic response to the serpent's appearance, perhaps

indicates her awareness of its existence and even her awareness of the possibilities the

serpent presents. In general, the “serpent” represents all things in God's “good” creation

that presents options to humans that might ultimately entice them away from God.

According to Strong, temptation has two meanings: 1) any attempt to entice or tempt into

evil, and 2) a testing that aims at an ultimate spiritual good (1802). Both aspects are

active in the garden and between the two extremes stands the tree in the middle of the

garden.

The author of Genesis writes: “He [the serpent] said to the woman, Did God say,

'You shall not eat from any tree in the garden?' The woman said to the serpent, We may

eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; but God said, 'You shall not eat of the fruit of

the tree in the middle of the garden, nor shall you touch it, or you shall die.' But the

serpent said to the woman, You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your

eyes will be opened and you will be like God” (Genesis 3:1b-5). Thus, the second most

important contrast is life and death. Both life and death correspond to creative elements:

dust and flesh, and spirit. As indicated above, living life to the fullest and eating of the

tree of life has been freely offered. Just as the potential for evil exists in the idyllic setting

of the garden, so too, the potential for immortality. However, this potential is requisite

upon the maintenance of the divine-human relationship. For example, part of the

judgment delivered to Adam, “you are dust and to dust you shall return,” suggests the

loss of a more enduring life (Genesis 3:19). Moreover, the lengthy age of the post

expulsion Adamic generations, perhaps, indicates a gradual loss of the longevity

29

associated with Eden. As humans drift further and further from the divine, their

transgressions are reflected in their length of days. “Then the Lord God said, 'My spirit

shall not abide in mortals forever, for they are flesh; their days shall be one hundred

twenty years'” (Genesis 6:3). Therefore, just as God chose to animate the flesh with spirit,

he chose to un-animate the flesh through its removal--death.

Flesh, then, indicates the physical (flesh/dust) and spiritual (breath/wind) aspects

of living; death indicates the physical and spiritual aspects of dying. The serpent's

question cleverly challenges this concept: “Did God say, 'You shall not eat of the fruit of

any tree in the garden?'” (Genesis 3:1). Fretheim asserts, “This tactic sets the agenda,

which centers on God, and provokes a response by suggesting that the woman knows

more about the prohibition than the serpent does.” He continues, “The question is clever,

to which a simple yes or no response is impossible, if one decides to continue the

conversation (a key move in such situations)” (I : 360). Through the use of flattery, the

serpent tests the woman's trust in what God has said. The dialogue implies that the

woman knows the prohibition better than the serpent, perhaps she also knows better than

God as well. In addition, the serpent not only challenges which fruit, but which death.

Indeed, the couple did not die in the physical sense.

Just prior to the expulsion, God addresses the heavenly court with concerns

regarding immortality: 'See, the man has become like one of us, knowing good and evil;

and now, he might reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life, and eat, and live

forever' (Genesis 3:22). This may seem contradictory to the freedom of eating of its fruit

in the preceding chapter; however, one of two possibilities exist. First, the concern may

30

reflect the couple's neglect in sampling the fruit. More likely though, it suggests a

developmental relationship through which (a type of) immortality is earned. In this case,

immortality is a process, such as eating daily for physical nourishment and worshiping

daily for spiritual nourishment, something one must work at to gain. In the garden, the

focus was not work, but worship, which indicates spiritual possibilities. The curse

focuses on work with an implied decrease in time for worship (relationship, quality of

life, etc.). The story in no way attempts to prove a doctrine of immortality, yet,

throughout the Bible it is assumed as an undisputed postulate. Therefore, the condition of

believers in their state of immortality is not a bare endless existence but a communication

with God in eternal satisfaction and blessedness (Strong 1725). In contrast, evil is

acquired quite easily through sensory perceptions: seeing, touching, tasting.

The clever antics of the serpent expose the appealing allure of that which God

called evil. “You will be like God,” the serpent tells the woman, but only in one way,

“knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:5). Therefore, it is not likely that Eve's acquisition

of the fruit was to gain knowledge or to be like God. Rather, Eve more likely wondered if

God was telling the truth--a risk Eve considered worthwhile. The intimacy of their

relationship had not been enough. Consequently, Eve exercised another aspect of being

created in the image of God--the freedom of choice. Fox maintains that “rebellion against

or disobedience toward God and his laws results in banishment/estrangement and literally

or figuratively, death. Thus from the beginning the element of choice, so much stressed

by the Prophets later on, is seen as the major element in human existence” (16-17). The

creative action found in “and God said” indicates purposeful action--God's choice in his

31

creation. In addition, the book of Jonah reveals that God himself can change his mind:

“When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil ways, God changed his

mind about the calamity that he said he would bring upon them [destruction of Nineveh];

and he did not do it (Jonah 3:10). Likewise, the command to “let them have” dominion

and the ability to subdue, “according to our likeness,” implies that humankind, like

heavenly beings, have the choice of how they will proceed in the newly created world.

In a particularly challenging verse, Paul makes a strong assertion regarding

women and the divine retinue. He writes, “For this reason a woman ought to have a

symbol of authority on her head because of the angels” (Cor 11:10, see note). “Some

translators assume that Paul was speaking metaphorically when he wrote of authority for

women, and so they word this sentence, “Therefore, a woman ought to wear a veil

because of the angels.” What would wearing a veil have to do with angels? Tertullian

offered one suggestion. He believed that if angels looked down and saw women without

veils, they might fall in love with them,” writes Bristow (87). This is an unlikely

scenario. The word Paul uses is exousia and never corresponds to an article of clothing,

but is the equivalent of “power,” “right,” “strength,” and “authority” and is used in

regards to kings and magistrates. In addition, it is used in regards to Christ's authority in

heaven and earth (Bristow 87). The “on her head” relates to her freedom of choice (Cor

11:10, annotations x and w). Therefore, woman has the authority to exercise her freedom

of choice because she has a greater sensitivity to her divinely inspired attributes. This

spiritual authority given to women was foreshadowed by the action of angels. An angel

came to Mary to enlist her cooperation in the birth of the Christ child (Luke 1:30-31).

32

Moreover, two angels announced the resurrection of Jesus to Mary Magdalene, Joanna,

and Mary the mother of Jesus at the empty tomb (Luke 24: 1-12). The appearance of the

angels to the women affirms the spiritual authority that women (and men) may choose to

enjoy from God as reflections of his divine image.

The image is not corporeal but rational, spiritual, and social, a reflection of the

divine. The earthly realm is the playing field upon which human choice is exercised. God

is active, but not intrusive in this realm. Like the naming of the animals, he allows for

human choice; however, choice corresponds to relationship quality, blessing, or

expulsion. God and the other divine beings already “know” evil, the prohibition was a

protective measure for the benefit of humankind. Therefore the couple's tasting of the

fruit is not related to the idea that knowledge and mortality are inextricably linked, but

rather that obedience and responsibility ensure blessing--it is all a matter of choice. The

serpent acts as a catalyst in assisting the woman's own mental processes to discover the

freedom she had the power to grasp (I : 366).

However, “looks good,” “feels good,” “tastes good” does not define the long term

goodness of the choice. Disobedience, pride, sin, whatever the label, leads to a death that

is possible to avoid. The spiritual aspects of living and dying, discussed above, are

completely within the power of humankind. Fox suggests a psychological point of view:

The story resembles a vision of childhood and the transition to the contradictions

and pain of adolescence and adulthood. In every way--moral, sexual, and

intellectual--Adam and Havva (Eve) are like children, and their actions after

partaking of the fruit seem like actions of those who are unable to cope with new

33

found powers. The resolution of the story, banishment from the garden, suggests

the tragic realization that human beings must make their way through the world

with the knowledge of death and with great difficulty.

(17)

This reading is far too simplistic and leaves too much of the given information

unexplored. According to the creative term bara', every potential existed in the

beginning: wisdom, knowledge, life, progress, etc., hence the creation of humankind as

adults--all potentialities are within the grasp of adult cognition. However, the “good” (not

perfection) of creation allows for growth and the development of potentialities, so too, its

corruption. Fretheim asserts, “By the way human responsibility for what happened is

lifted up, the writer does not assign the problem of human sinfulness to God or consider it

integral to God's creational purposes. Certainly God creates the potential for such

developments for the sake of human freedom. Especially important are the effects of this

human decision, which ranges in an amazingly wide arch; it disrupts not only their own

lives, but (given the symbiotic character of creaturely relationships) that of the entire

cosmos as well, issuing in disharmonious relationships at every level” (I : 368).

The curse involves a transformation in the primary roles in life, roles of stature

among the animals, roles of wife and mother, roles of laborer and provider. Every

conceivable relationship has been disrupted: among the animals; between an animal and

humans; between the earth (adamah) and humans; between human beings and God;

between an animal and God; within the individual self (e.g., shame, guilt, and alienation).

The man and woman bear the consequences of their own choices. Accordingly, it must be

34

noted here that 'ādām (humankind: male and female) functions generically in this section

of the story.

This overlap indicates the necessity of reading the story of paradise as the first

part of the creation story. Humankind must have a reference point of relationship and

behavior, the “it was good” from which to move. God provides the example for this as

anything in the garden deemed “not good” was rectified. Evil however, is a different

matter. Evil is presented as the antithesis of morality, integrity, relationship and

completeness, and thus shown to dissolve community, a fragmentation that spreads

dissolution and effects the whole cosmic order. In this light Armstrong writes, “But

perhaps we can see the sin of Adam and Eve as a refusal to accept the nature of things . . .

A lust for life can be an expression of rampant egotism and desire for self

aggrandizement which takes no care for the rest of the world” (31). Eden is meant to

provide a sharp contrast to the rest of the world. It is not only a place but an attitude, a

frame of mind where evil cannot live if one desires a natural balance of things. The most

assertive movement away from the natural balance of things is found in the more specific

symbolism attached to the encounter between Eve and the serpent.

35

Chapter 6

EVE, THE SERPENT, THE CITY, AND MYTH

The clothing of Adam and Eve prior to expulsion from the garden foreshadows

the more specific symbolism attached to Eve and the serpent that will eventually

culminate in her offspring Cain. However, clothing the divine couple offers a certain

degree of ambiguity in association with the expulsion. It is both punitive and protective.

God makes good on his promise of (spiritual) death should the couple choose to violate

his law; and it seems that God underscores the newly found knowledge of shame by

double-clothing the couple. Yet, the clothing offers protection for the couple to the life

that awaits them outside of Eden: not garments as a protective covering per se, but as a

preliminary introduction to social convention.

Faced with the options presented by the serpent, Eve and Adam move one step

away from Eden and one step closer to the city. Accordingly, Jeremy Black and Anthony

Green authors of Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated

Dictionary maintain, “Representations of snakes are naturally frequent in iconography

from the prehistoric period onwards, but it is not always easy to decide whether or not

they carry any religious value.” (167) However, several attributes remain certain: 1) when

depicted as attributes of deities serpents are seen associated with both gods and goddesses

(167), 2) serpents are associated with “Slain Heroes (164), and 3) serpents and serpentine

monsters can be a metaphor for gods and kings (71). Therefore, if Eve represents life,

living, and permanent settlements and the serpent represents gods, myths, and kings the

point of intersection must be civilization and technology. Along these lines, one must

36

question the redactor's motivation in writing the text. Is the redactor suggesting an

exhortation against progress? To those with modern day sensibilities, this may seem most

disturbing. However to further complicate the issue, the answer is both yes and no. What

happens in the garden manifests itself in disharmonious relationships that accompanies

the history of humankind outside the garden.

The abrupt transition to life outside the garden appears initially positive, with the

intimacy between the husband and wife and the birth of children. Maintenance of a

creational theme appears foremost: Adam and Eve fulfill the creational command to “be

fruitful and multiply” and Cain and Abel fulfill the commands to “have dominion” and

“subdue the earth.” Moreover, the initial focus of the text remains in the context of

worship; however, it is in this context that the dissension between the brothers arises.

Evidence of the impending clash ensues from Eve's cry: “I have produced a man with the

help of the Lord” (Genesis 4:1). Here, the verb “produced” plays upon Cain's name and

foreshadows his approaching future.

Cain (qayin) means “brought forth,” “acquire,” “smith,” and “metal worker”

(Strong 1561), implying an immediate conflict with the nature of things. Moreover, as a

“tiller of the ground,” Cain's chosen occupation operates within the realm of the curse:

“By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread” (Genesis 3:19). “Sweat” and “bread”

refer to the arduous and tedious processes required in grain cultivation. Agriculture was

the key development that led to the rise of civilization (and animal husbandry) creating

food surpluses that enabled the development of more densely populated and stratified

37

societies. H.W.F. Saggs, author of Babylonians: Peoples of the Past, attests to these

developments:

Civilisation, in the same sense of a way of life associated with cities and writing,

began in south Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium. But this was not the

sudden single- handed achievement of a master race. Behind it lay many millennia

of human advance. Already, 300,000 years ago, an early form of man using fire,

and fashioning tools and weapons. Our own form of man, Homosapiens, emerged

in Africa by 90,000 BC and by 30,000 BC had supplanted neanderthal man

throughout Europe. Soon after, trading was taking place as far away as 400 km

(250 miles) from the supply base, as the distribution of flint from an identifiable

source in Poland shows. By 20,000 BC man had invented the needle, a tool which

greatly facilitated the making of clothing for the protection against the bitter cold

of the last Ice Age. Man had also learnt many other skills: he could control the

movement of herds for more effective hunting; he knew how to store food;

and he could build shelters and long-term camp sites. These last achievements

prepared the way for further advances, since it was only a step from storing wild

cereals to sowing and cultivating them, and it was an easy transition from semipermanent camp sites to permanent villages.

(23)

This brief historical record is represented through the Adamic family, particularly the

later developments which are realized through the genealogy of Cain. These latter

developments began after the end of the last Ice Age, from about 90,000 BC, running in

an arc from Palestine along the foothills of the Taurus to the foothills of the Zagros. The

38

presence of wild sheep and goats, wild wheat and barley, and plentiful rainfall made these

developments possible. Genesis 2:16-3:23 reflects these beginnings “when it tells how

mankind, after first living in a garden where food was to be had for the gathering, was

driven out to an existence dependent on tillage of the soil” (Saggs 23).

In contrast to Cain, Abel is a “keeper of sheep” (Genesis 4:2). Although Cain is

the eldest brother, Abel and his occupation precede Cain's in the text. Abel's prime

placement in the story underscores his harmonious relationship with God, his family, and

the earth. He fulfills the creational command to ŝāmar (preserve and keep) the earth and

its creatures. Moreover, Abel is translated as “meadow,” and “morning mist,” something

more “transitory” (Strong 1492). The importance of the transitory association to Abel's

character offers a tripartite explanation of the text. First, it foreshadows Abel's transient

existence on the earth. Second, it perhaps suggests that city living can kill the

righteousness of humankind; and last, it provides a sharp contrast to a static population

that exhibits a greater harmony with the natural world. Thus, God accepts Abel's

sacrifice; but “for Cain and his offering he had no regard” (Genesis 4:5).

God looks at both the offerer (the intentions of the heart) and the offering (Heb

11:4; 1 Sam 16:7). Cain's offering of “the fruit of the ground” is reminiscent of the

transgression in the garden just prior to expulsion. Fruit (pᵉ rî) means not only fruit, as in

produce, but also the “result of any action” good or evil (Strong 1555). Hence, it is likely

that the inward character of Cain and Abel are defined through their occupations. Thus,

before God, Cain did not “do well.” The external manifestation of his inward character

39

presents itself through Cain's anger and fallen countenance. Therefore, God offers Cain

advice:

Why are you angry and why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you

not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is lurking at your door; its desire

is for you, but you must master it.

(Genesis 4:6-7)

Finally, the disharmony within the creation receives a label-- “sin.” The reality of sin is

portrayed as something active and predatory, a potentially consuming fact of life that can

control every aspect of Cain's seeing, touching, and tasting (thinking, feeling, and acting).

Conquering sin, therefore, requires self-control and self-mastery. Perhaps, the redactor

suggests that self-control is the only way to reclaim that which was lost in Eden--through

the maintenance of a paradisaical attitude within the self. For certain, the redactor

purports that the choices of humankind genuinely make a difference regarding the shape

of the future.

However, the reality of sin continues and intensifies Cain's problematic

relationship to God, to others, to the ground, and to himself. For God's advice, Cain had

no regard. He lures his brother to the field and murders him. God is aware of the

homicide, yet he moves to elicit a confession from Cain. Rather than hiding from God,

Cain tells a bold-faced lie. Even more, he turns the question back on God: “Am I my

brother's keeper?” (Genesis 4:9). Cain negates God's command to ŝāmar, he has no

intention of keeping and preserving any part of creation, not even his own brother.

Moreover, by setting the conflict between the brothers in the context of worship, the

redactor alludes to the birth of religion. The more specific allusion is toward polytheism

40

and its direct association with the material aspects of civilization and technology. The

admonition is not against progress per se, but the exploitation thereof. Material progress

frequently outruns moral progress and human ingenuity, so potentially beneficial to

humankind, is often directed towards evil ends (I : 377). This idea resonates strongly in

that the first murder arises in the context of worship. Cain's act not only violates the

cosmic order, but its creator. By taking a life, Cain appropriates to himself a godlike

power over Abel's very existence. Religion, thus, is merely one of the ways by which

men seek to get what they want, to satisfy their desires, and avoid the dangers they fear

(Burrows 154). Humans remain non-religious when all their needs are met as illustrated

by life in the garden. Nevertheless, God remains the evaluator.

Like the sentence meted out to his parents, Cain's sentence is both punitive and

protective. The story maintains the close relationship between humans and the land, and

underscores the link between the moral order and the cosmic order. Although Cain's

“sins” are not intentionally directed toward the ground, the shedding of human blood

adversely affects the productivity of the soil. The prophet Hosea sheds light on the moralcosmic link:

Hear the word of the Lord,

O people of Israel;

for the Lord has an indictment

against the inhabitants

of the land.

There is no faithfulness or

41

loyalty,

and no knowledge of God in

the land.

Swearing, lying, and murder,

and stealing and adultery

break out;

bloodshed follows bloodshed.

Therefore the land mourns

and all who live in it languish;

together with the wild animals

and the birds of the air

even the fish of the sea are

perishing.

(Hosea 4:1-3)

Human behaviors that do not manifest themselves in the consciousness of others, will

nonetheless, come to the consciousness of God. The creation itself both records and

reveals the abuses of humankind. Abel's blood cries out to God from the ground. The

ground “which has opened its mouth” to receive Abel's blood will no longer produce any

yield, regardless of Cain's efforts, and Cain “will be a fugitive and a wanderer on the

earth” (Genesis 4:12). Cain laments his sentence--the murderer fears for his own life.

Here, Cain appears cognizant of the population even further outside of Eden. (The

humans from the sixth day of creation). Yet, God promises that should anyone kill Cain,

he will be avenged seven-fold. Cain prepares to enter the existing order of things, the

42

present customs, practices, and power relations in the world at large. Placing a mark on

Cain establishes God's care for him and sets him apart as a believer in Yahweh. (The

interaction between Cain and God establishes this belief). The evaluation Cain receives

intensifies the earlier curse and displaces him even further East from the garden. Cain is

removed from the presence of the Lord and he settles in the land of Nod or “wandering”

(Strong 1535).

As Cain's name and occupation foreshadow, it is not surprising that within the

existing population, Cain finds a wife with whom he begins the Cainite genealogy and

builds the city of Enoch named after his son. From the line of Cain arises permanent

settlements, stock-breeding, musicians, and metallurgy--trades all vital to the rise of cities

(Genesis 4:17-22). However, “to 'settle' in 'wandering,' an ironic comment, may refer to a

division within the self, wherein spatial settledness accompanies a troubled spirit (see Isa

7:2). That Cain founded a city (nothing is said about the nature of the city) suggests that

rootlessness means more than physical wandering. Those who live in cities can also be

restless wanderers,” asserts Fretheim (I : 375). With the rise in population and

advancement in technology, sin intensifies and humankind is further distanced from the

divine, from nature, and from natural theology. In this portion of the story, Lamech

exemplifies this intensification.

It is from the offspring of Lamech that the material aspects of the civilizing

process come to the fore. Moreover, betraying the original intent of monogamous union,

Lamech is the first polygamist. This bold maneuver perhaps implies Lamech's doubly

sinful nature. Moreover, there is an interesting ambivalence associated with Lamech and

43

his family. Nomenclature plays the predominant role here, and the pairing of names is

most significant. For example, Adah is the mother of both Jabal and Jubal. Adah means

“adornment” (Strong 1544) and Jabal and Jubal both translate as “stream” or