Academic Advising and Cultural Competency An existential-phenomenological approach to student wellbeing

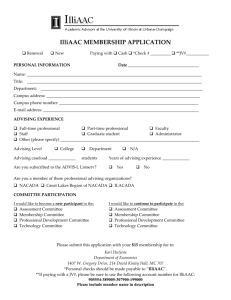

advertisement

Faculty of Education and Social Work Academic Advising and Cultural Competency An existential-phenomenological approach to student wellbeing Dr Remy Low Faculty of Education and Social Work This presentation 1. Academic advising 2. Cultural competency 3. Aboriginal spirituality 4. The phenomenological attitude 5. An existential model 6. Case studies 7. Concluding reflections 2 Academic advising What is academic advising? › “refers to situations in which an institutional representative gives insight or direction about an academic, social, or personal matter” (Kuhn 2008, p.3) › “Academic advising, based in the teaching and learning mission of higher education, is a series of intentional interactions with a curriculum, a pedagogy, and a set of student learning outcomes. Academic advising synthesizes and contextualizes students’ educational experiences within the frameworks of their aspirations, abilities and lives to extend learning beyond campus boundaries and timeframes.” (NACADA, 2006) - minority students in the United States perceive academic advising by faculty members as the most important of seven support services, including career planning or placement, minority student programs, counselling, housing or residential life, student activities, and student affairs or dean's offices. (Burrell & Trombley, 1983) 3 Cultural competency What is cultural competency? › “Cultural competence is the ability to participate ethically and effectively in personal and professional intercultural settings. It requires being aware of one’s own cultural values and world view and their implications for making respectful, reflective and reasoned choices, including the capacity to imagine and collaborate across cultural boundaries. Cultural competence is, ultimately, about valuing diversity for the richness and creativity it brings to society.” (NCCC) 4 Aboriginal spirituality The foundation of practice › “Spirituality includes Indigenous Australian knowledges that have informed ways of being, and thus wellbeing, since before the time of colonisation, ways that have been subsequently demeaned and devalued. Colonial processes have wrought changes to this knowledge base and now Indigenous Australian knowledges stand in a very particular relationship of critical dialogue with those introduced knowledges that have oppressed them. Spirituality is the philosophical basis of a culturally derived and wholistic concept of personhood, what it means to be a person, the nature of relationships to others and to the natural and material world, and thus represents strengths and difficulties facing those who seek to assist Aboriginal Australians to become well.” (Grieves, 2009, p.v) › “The starting point for wellbeing is always cultural in that it is defined, understood and experienced within a social, natural and material environment, which is understood and acted on in terms of the cultural understandings that a people have developed to enable them to interact within their world” (Grieves, 2009, p.2). 5 Aboriginal spirituality The foundation of practice › “It is thus a fundamental principle that an understanding of Aboriginal wellbeing needs to take into account the different ontologies (understandings of what it means to be) and epistemologies (as ways of knowing) that characterise the experience of colonised peoples.” (Grieves, 2009, p.2) › “The tendency for many people from the dominant society, confronted with differences in attitudes or behaviour that is strange or odd, is to demean people from other cultures in some way, or to construct them as exotic and therefore worthy of further inquiry. This is due to the fact that most people are brought up as ethnocentric... this makes it difficult to even appreciate how different difference can be. Your commonsense may not be commonsense at all for another person. Ethnocentrism influences how we think, observe, interpret and understand. It can influence how we diagnose, how we treat, and how we evaluate outcomes. We need to suspend our judgments of difference to understand others in their own terms.” (Grieves, 2009, p.40) 6 Adopting a phenomenological attitude 3 basic rules in practice 1. Epoché (or “bracketing”): We temporarily suspend our assumptions about the world and our preconceptions (see Van Deurzen, 2012, p.9; also Spinelli, 1989, p.17) 2. Description: Instead of naming and labelling, we take the time to listen and (re)describe the experiences of our students slowly and carefully (see Van Deurzen, 2012, p.9; also Ihde, 1986, p.34) 3. Horizontalisation: We avoid placing any initial hierarchies of significance or importance upon descriptions, and instead treat every element of the description as having equal value or significance (see Spinelli, 1989, p.18; also Van Deurzen, 2012, p.9) 7 An existential model Lifeworlds › “Aboriginal Spirituality derives from a philosophy that establishes the wholistic notion of the interconnectedness of the elements of the earth and the universe, animate and inanimate, whereby people, the plants and animals, landforms and celestial bodies are interrelated.” (Grieves, 2009, p.7) › “We are complex bio-socio-psycho-spiritual organisms, joined to the world around us in everything we are and do.” (Van Deurzen, 2010) 8 An existential model Lifeworlds Spiritual Social Personal Physical 9 Culturally competent academic advising An existential-phenomenological approach Case studies: - “Neven” - “Ken” - “Nancy” 10 Concluding reflections What are the limits of this approach in the context of higher education? › Time › Centralisation of processes › Prevailing practices based on a particular ontological and epistemological premise 11 References Burrell, L.F., & Trombley, T.B. (1983). Academic Advising with Minority Students on Predominantly White Campuses. Journal of College Student Personnel, 24(2), 121-26 Grieves, V. (2008). Aboriginal Spirituality: A Baseline for Indigenous Knowledges Development in Australia. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 28(2), 363-398. Grieves, V. (2009). Aboriginal spirituality: Aboriginal philosophy, the basis of Aboriginal social and emotional wellbeing. Casuarina: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health. Ihde, D. (1986). Experimental Phenomenology: An Introduction. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Kuhn, T.L. (2008). Historical Foundations of Academic Advising. In V.N. Gordon, W.R. Habley, & T.J. Grites (Eds.), Academic advising: A comprehensive handbook (pp.3-17). San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. National Academic Advising Association [NACADA]. (2006). NACADA concept of academic advising. Retrieved from http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/ViewArticles/Concept-of-Academic-Advising-a598.aspx Van Deurzen, E. (2010). Everyday mysteries: A handbook of existential psychotherapy. London: Routledge. Van Deurzen, E. Van. (2011). Existential counselling and psychotherapy in practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Spinelli, E. (1989). The Interpreted World. London: Sage. 12