‘He really leant on me a lot’:

‘He really leant on me a lot’:

Parents’ Perspectives on the Provision of Support to Divorced and Separated

Adult Children in Ireland

Authors:

Timonen, Virpi, Doyle, Martha and O’Dwyer, Ciara – all of Trinity College

Dublin, Ireland

Corresponding author:

Dr Virpi Timonen

School of Social Work and Social Policy

Arts Building

Trinity College Dublin

Ireland

Tel. + 353 1 896 2950

Fax + 353 1 671 2262

timonenv@tcd.ie

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by the Family Support Agency of Ireland.

1

‘He really leant on me a lot’:

Parents’ Perspectives on the Provision of Support to Divorced and Separated

Adult Children in Ireland

Abstract

The literature on intergenerational transfers and divorce has paid little attention to the experiences of older adults whose son or daughter has divorced or separated. We conducted 31 qualitative interviews to explore support provision from the perspective of older adults with divorced or separated adult children. All respondents were also grandparents. Older adults whose sons and daughters have experienced divorce or separation seek to accomplish two main aims, namely (a) compensating for the perceived losses that their adult children (and grandchildren) have experienced and (b) drawing boundaries around the support that they channel in order to compensate for the losses.

The findings support the relevance of both the solidarity and ambivalence paradigms in seeking to understand post-separation intergenerational relationships and transfers, and hence the argument that these frameworks are compatible and complementary.

Keywords : divorce, separation, intergenerational supports, older adults, solidarity, ambivalence.

2

Introduction

The impact of divorce and separation on parent-adult child relations has been approached from the perspective of the older divorced generation (ageing parents) or the younger divorced generation (adult children). The main foci of this body of research can be divided into (a) the impact of divorce on intergenerational transfers (of care and support, money) and (b) the quality of relationships between the adult children and their parents following divorce in the younger or the older generation.

Research on intergenerational transfers in families affected by divorce has typically focused on transfers between ageing parents who have divorced or separated and their adult children, and to a lesser extent on adult children who have divorced and the support they receive from their parents. One of the motivations for this branch of research is a concern with the potentially deleterious impact of family instability on the availability of care and support to divorced or separated individuals as they age. Some of the (partly conflicting) findings in the literature are that divorced or separated fathers receive less support in older age than their married or widowed counterparts (Dykstra 1997); that both divorced and widowed mothers are more likely to receive support from their adult children than mothers with partners (Stuifbergen, Van Delden and

Dykstra 2008); that divorce between a couple lessens solidarity from younger generations

(Daatland 2007); that partnership dissolution does not have a detrimental impact on availability of support in later life (Glaser, Stuchbury, Tomassini and Askham 2008); and that father-child relationships are more susceptible than mother-child relationships to change following divorce

(Tomassini et al. 2004; Berger and Fend 2005; Lye 1996; Lin 2008).

Relative to this extensive literature on intergenerational transfers from adult children to ageing divorced parents, the body of literature on the supports that ageing parents provide to their divorced or separated adult children is much smaller. Gerster (1988) has shown that kin are a

3

significant source of practical support to divorced men and women. Financial help and assistance with childcare have been argued to be prevalent (Leahy Johnson 1988) and resumption of coresidence to be common, especially for adult sons with low socio-economic status (Sullivan,

1986). Beyond the specific focus on contexts of divorce and separation, the literature on grandparents’ supportive roles within extended families is very extensive and has yielded, among other insights, the argument that grandparents can act as ‘child savers’ (where parents are not able or willing to look after their children) and as a ‘reserve army’ that steps in at times of difficulty and hardship (Hagestad, 2006).

The literature provides contradictory findings on the impact of divorce on the quality of relationships between divorced adult children and their ageing parents. Gray and Geron (1995:

139) argue that ‘[d]ivorce entails a rupture in the changing roles assumed by parents and adult children as they age, and often thrusts one or both grandparents and their children into earlier parent-child relationships’. Kaufman and Uhlenberg (1998) found that both parental divorce and problems in a child’s marriage strain the adult child-parent relationship. Other studies have suggested that the negative impacts of an adult child’s divorce on intergenerational relations are perhaps overstated. Spitze, Logan, Dean and Zerger (1994, p. 291) write that ‘[d]ivorce does not decrease interaction with children, nor does it affect feelings of closeness’ and that ‘[a]ny negative consequences for parents are probably…limited to those directly caused by short-term provision of financial or child-care help beyond comfortable levels’.

Bengtson (2001) has argued that an increase in marital instability will make relationships with extended kin more important, and Dykstra (1997) found that divorce in the younger generation strengthens parent-child ties. It has also been argued that the dissolution of marriage may bring about a revival in parent-adult child relationships, at least as measured by frequency of interaction. Sarkisian and Gerstel (2008) used data from the United States to produce evidence

4

that married men and women have less intense ties with their parents than the never married and the divorced. Co-residence, keeping in touch and receipt and provision of financial, practical and emotional help were less common among the married than the unmarried and the divorced. The authors conclude that ‘marriage is a greedy institution for both men and women’, and that separation and divorce lead to at least a temporal increase in the intensity of inter-generational ties, particularly in contexts where there are young children (Sarkisian and Gerstel 2008, pp. 360-

361). They furthermore argue that the divorced and separated can in most respects be placed between the never married (who interact most intensely with their parents) and the married (who interact least intensely with their parents); this is because the divorced have not managed to resuscitate the relationships to the same level that the never married have sustained with their parents.

Literature on older adults’ experiences of their adult children’s relationship breakdown has tended to focus on the strains that can ensue from divorce in the younger generation, and the parental generation’s feelings of confusion, disappointment, shame and other negative reactions that manifest themselves in intrusiveness and criticism directed at the adult child (Cooney and

Uhlenberg 1990, Leahy Johnson 1988, Spanier and Hanson 1982). Children’s marital problems have been linked to parents’ psychological distress in research by Grenberg and Becker (1988) and Johnson and Vinick (1982). Pearson (1993) highlighted the negative experiences of grandparents such as embarrassment, loss and feeling upset and argued that older parents became more upset over time in a four-year longitudinal study. Grandparents’ reactions are shaped by the context within which they experience their adult children’s relationship breakdown and may have become more accepting as divorce has become more commonplace.

When we consider the literature on the impact of divorce in the younger generation on intergenerational relationships in tandem with the literature on the impact of divorce on

5

intergenerational transfers, some interesting observations can be made. On the one hand, divorce in the younger generation can lead to more intense relationships between them and their parents; on the other hand, the quality of these relationships often declines. This may not be very surprising, as the quantity of interaction with a person is not necessarily linked to the quality of that interaction. However, a number of questions arise. For instance, how do parents whose adult children have experienced relationship breakdown perceive and react to the situation, and how (if at all) do they think it alters their relationship with the adult child and grandchild(ren)?

The theoretical construct of intergenerational solidarity (Bengtson and Schrader 1982; Bengtson,

Biblarz and Roberts 2002; Bengtson et al. 2002) consists of six principal dimensions, namely affectual solidarity (emotional closeness), functional solidarity (help and support), structural solidarity (geographical proximity), consensual solidarity (agreement in opinions and values), normative solidarity (norms and expectations) and associational solidarity (frequency of contact).

Following the inclusion of feelings of conflict into the model, the theory is sometimes referred to as the solidarity-conflict model (Giarrusso et al. 2005, p. 414).

Luescher and Pillemer (1998, p. 414) have argued that ‘intergenerational relations among parents and their adult children can be social-scientifically interpreted as the expression of ambivalences and as efforts to manage and negotiate these fundamental ambivalences’. Pillemer et al. (2007) define ambivalence as ‘the simultaneous existence of positive and negative sentiments [in the older parent-adult child relationship]’ (see also Bengtson et al. 2002). Luescher and Pillemer have argued that ‘countervailing positive and negative forces characterize intergenerational relationships and that the focal point of interest is the way in which ambivalence is mediated and managed’ (1998, p. 420) .

They also express the belief that ‘[s]tatus transitions provide perhaps the best laboratory for the study of intergenerational ambivalence’ (1998, p. 423).

Drawing on qualitative pilot interviews and focus groups, Pillemer and Suitor (2002) developed a five-item

6

measurement of ambivalence, and asked 189 mothers aged 60 and over about the extent to which, in the relationship with their child, they felt ‘torn in two directions or conflicted’, had ‘very mixed feelings’, ‘got on each others’ nerves yet felt close’, had an ‘intimate’ but also ‘restrictive’ relationship, and experienced feelings of ‘indifference’ despite loving the child ‘very much’

(2002: 607). Pillemer and Suitor (2002) went on to show that older mothers’ experiences of intergenerational ambivalence were related to adult children’s ‘failures’ to achieve and maintain normative adult statuses (marriage, financial independence).

Connidis and McMullin (2002) have developed the concept of structural ambivalence , that is,

‘socially structured contradictions made manifest in interaction’. Pressures and competing claims on resources induce stress in relationships that in turn can act as a motivator of action, manifest for instance in negotiating relationships. The emphasis on individuals’ agency is an important aspect of Connidis and McMullin’s contribution to the literature on ambivalence: ‘individuals experience ambivalence when social structural arrangements collide with their attempts to exercise agency when negotiating relationships’ (Connidis and McMullin 2002: 565).

Giarrusso and colleagues have recommended that research should address ‘the extent to which parents or children perceive feelings of ambivalence’ and ‘identify whether transitions [between solidarity and conflict] come in response to life events such as…divorce…in the younger generation’ (Giarrusso et al. 2005, p. 419, emphasis in the original). Adult children’s divorce and separation can be triggers of intergenerational conflict, solidarity or ambivalence. This article sets out to explore the impact that a status transition by adult children (from married/partnered to divorced or separated) had on their parents. Our focus lies both in intergenerational transfers and the quality of the relationship, as experienced and recounted by older parents themselves.

Research Questions

7

There is very little research that directly examines the nature of intergenerational transfers and relationships in the context of divorce or separation in the younger generation from their parents’ perspective. This article analyses the supports that the older generation provides to the younger generation(s) and the impact that these have, from the parents’ perspective, on their relationships with their adult children.

This article seeks to deepen our understanding of (a) older adults’ experience of support provision to their adult children during and after the latter’s relationship breakdown and (b) their perceptions of how support provision in the context of divorce or separation influenced the relationship with their adult children. By focusing on older parents’ perceptions of a major status transition in their adult children’s lives, this article follows the recommendations for research contained in the literature, and offers an exploration of both the solidarity and ambivalence frameworks in this context. The article is derived from a study which aimed to broaden our understanding of the role played in Ireland by grandparents within families where the adult child had been separated or divorced. Our study did not focus on identifying or measuring the relative impact of the factors that influence the nature or extent of support provision. Readers interested in these are referred to previous research that has identified gender, age, geographic distance, prior relationship quality, financial and employment status, parents’ time and other resources, and the presence of grandchildren as factors that impact on intergenerational support at the time of divorce in the younger generation (e.g. Gerstel 1988, Lye 1996, Spitze, Logan, Dean and Zerger

1994).

Context

We undertook this research in Ireland, a country where divorce has been legal only since 1995 following a referendum that was carried by an exceedingly narrow majority. The total number of individuals who have experienced marital breakdown in Ireland (legal separation or divorce,

8

including those who subsequently remarried) increased from 40,000 in 1986 to nearly 200,000 in

2006 (Fahey, Lunn and Hannan 2009). Despite this rapid increase, the divorce rate is low in comparison to most Western countries (Lunn, Fahey and Hannan 2009), and the formal support services for individuals and families experiencing relationship breakdown are arguably still relatively underdeveloped. Divorce is a highly controlled and protracted process in Ireland: spouses must have lived apart for at least four years before initiating divorce proceedings.

Eggebeen (2005) and Nock (1995) have shown that marriages and other partnerships differ in many ways. Because our study was the first of its kind in Ireland and sought to scope the diversity of experiences, we sampled for parents of both adult children who had been married and those who had non-marital relationships.

Method

Overall approach

As the project focused on exploration of the interpretations and meanings that individuals (in our case, grandparents) attach to their experiences, we used a qualitative approach for the study. The adoption of a qualitative approach is also appropriate on the grounds that the topics outlined above are still poorly understood and under-theorised, certainly in the Irish context but also more generally.

Sampling

We recruited respondents through support groups and advice centres for divorced and separated adults, lone parents’ support groups and older people’s groups (yielding 15 respondents); advertisements were also placed in the main national newspaper of record ( The Irish Times ) and newsletters of the above organizations (yielding 16 respondents). Salient factors identified in the literature that examines post-divorce grandparent-grandchild relationships (gender, lineage) guided our sampling and recruitment process.

9

Sample characteristics

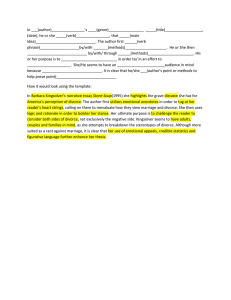

Table 1 below describes the sample by gender and lineage.

Gender and lineage are highlighted in the literature as key variables that influence contact and support provision between (grand)parents and (grand)children following marriage breakdown in the middle generation (Amato and Cheadle

2005). All respondents consented to having the interviews audio-recorded. The interviews ranged from 30 to 120 minutes in duration, and all were transcribed in full by a professional transcriber.

Table 1: Sample characteristics: Gender and lineage

Maternal Paternal

N

2

%

18.2

N

6

%

31.6

Both*

N

0 Male Respondent

Female Respondent 9 81.8 13 68.4 1*

%

0

100

Total

N

8

23

%

25.8

74.2

Total 11 100 19 100 1 100 31 100

*One female respondent had two children who had experienced relationship breakdown.

The relationship status of the respondents’ children was almost evenly divided between those who had been married and divorced; those who had been married and separated; and those whose non-marital relationships had come to an end. Nineteen respondents lived in rural, semi-rural or small town areas (population ≤ 5,000) and twelve in urban areas. The respondents ranged in age from early 50s to early 80s.

Data collection

A university ethics committee approved the study before interviewing commenced. The authors carried out the interviews between August and October 2008. The interview guide contained six sections. The two sections of relevance to this article focused on (a) support provision to the divorced/ separated adult child and (b) the respondent’s relationships with his/her child, the child’s partner and grandchild(ren) before and after the divorce or separation. We asked open-

10

ended and non-directive questions (e.g. ‘What kind of support have you provided to your son / daughter during and after the divorce / separation?’; ‘Can you tell me about your relationship with your son/daughter before/after he/she separated?’), and prompted respondents only to a minimal degree where necessary or when we identified interesting or incomplete lines of thought.

Analytic Strategy

All authors participated in carrying out the data analysis, and engaged throughout the interview and analysis stages in comparison of their coding, categorization and theorizing of the data, both during face-to-face team meetings and via e-mail correspondence. We used ‘support’ as the initial, broad analytic concept; we coded all data relating to ‘support’ and from these codes derived more specific concepts (different types of support); nuances and tensions within each category were analysed (axial coding) and incorporated into the analysis; through a process of selective coding, main themes within each category were subsequently collapsed into the two overarching themes (‘compensating’ and ‘drawing boundaries’) (Corbin and Strauss 2008; La

Rossa 2005). The core category of ‘compensating’ resonated with the concept of solidarity outlined above as demonstrations of solidarity are akin to attempts to compensate for (perceived and actual) losses experienced by family members; the core category of ‘drawing boundaries’ in turn relates to the concept of ambivalence as boundary maintenance is one of the activities people engage in when they experience ambivalent feelings. We re-read the interview transcripts at various points throughout the data analysis in order to check for accuracy and adequacy of evidence to support the categories and themes discussed in this article.

Findings

The supports given by the respondents to their adult children during and after the relationship breakdown processes fell into five main categories. In order of prevalence (starting with the most prevalent form of support, as measured by the number of grandparents referring to the support),

11

these types of support are: (a) emotional, (b) financial, (c) practical: child care-related, (d) practical: provision of housing (co-residence) and (e) practical: advice and assistance with legal and other official matters. These categories broadly match ones derived and outlined by previous research in other contexts, for instance by Mancini and Blieszner (1986). Table 2 summarises the number of respondents who had provided different types of support by lineage and their adult child’s former marital status.

Table 2: Number of respondents reporting provision of different types of support to their adult child by lineage

N

Maternal

(N=12)

%**

Emotional

Financial

Childcare

6

7

7

50.0

58.3

58.3

14

13

10

Co-residence

Legal and other advisory

2

2

16.7

16.7

11

6

* Total N=32 because one respondent had two separated adult children.

** Percentage of all maternal grandparents

†

Percentage of all paternal grandparents

N

Paternal

(N=20)*

%

†

70.0

65.0

50.0

55.0

30.0

Emotional Support

N

20

20

17

13

8

Total

(N=32)

%

64.5

64.5

54.8

41.9

25.8

Two-thirds of the respondents provided their adult child with emotional support. Emotional support was motivated by a concern for the well-being of the son or daughter, following what many respondents described as a traumatic and confusing upheaval for their adult child, regardless of the circumstances or amicability of the separation. Many grandparents perceived the immediate emotional impact of relationship breakdown on their adult child as drastic and its consequences as unfair towards their son or daughter. They were sympathetic towards their adult children who they believed had difficulty coming to terms with their changed circumstance postseparation:

12

And she's bound to have times when she's sorry for herself. The others probably see it too but I am with her more, I always have been…she came to me and I was with her to help her solve her problems...It's not that she comes and complains but I'd know.

(Respondent 29, maternal grandmother)

In most cases there was continuity in the basic quality of the parent-adult child relationships i.e. the relationship with the son or the daughter post-separation bore great resemblance to the relationship before the occurrence of separation. Where change was reported, it was in a positive direction:

I think [the divorce] hasn’t really affected [my relationship with my daughter] in any way. It’s always been a good relationship. We can talk and communicate very readily and we have just kind of shared this thing so I would think if anything, it has deepened it. It certainly hasn’t dis-improved it.

(Respondent 18, maternal grandmother )

A positive ramification of most types of support, and emotional support in particular, was an increased degree of closeness reported by the respondents, a finding that reflects affective solidarity. In all cases where extensive emotional support had been provided, the respondents felt that this had brought them closer to their adult child. In the following case the fact that the mother was to some extent compensating for the absence of the partner in social situations was one of the factors that brought her closer to her daughter:

I used to go out with her if we were going for a night out, going for a drink or anything. I am more inclined to go with her and say 'Come on it will be all right.' I got closer that way.

(Respondent 7, maternal grandmother)

13

The provision of emotional support had led some respondents to change their role in relation to their adult child considerably, reverting to the earlier roles of ‘protector’ and ‘comforter’:

She would depend on me an awful lot more now. She would text me and ring me every minute…

(Respondent 29, maternal grandmother)

The breakup also provided many grandparents with an opportunity to forge closer relationships with their grandchildren, through spending more time with them in everyday situations:

I was sitting over there in the chair and the television was on and I said to [granddaughter who wanted to watch television with him] it was the first time in my life that a lady asked me could she sit on my lap.

(Respondent 6, paternal grandfather)

Our sample contained very few cases where relationship breakdown in the middle generation had led to a significant deterioration in the quality of the relationship between the separating child and his or her parents; a complete breakdown in this relationship also seems very rare and is brought about by a confluence of factors, not the divorce or separation per se . A complete severing of the relationship with an adult child had taken place in only two cases: in the case of a grandmother whose daughter cut off all contact after she had sided with her former son-in-law in relation to disputed access to children, and in the case of a paternal grandfather, the sole custodial grandparent of his grandson, who found his son’s drug addiction impossible to handle.

Financial Support

Similar proportions of sons and daughters received financial support from their parents following relationship breakdown. However, there was a difference in the reasons for financial support provided to sons and daughters. In Ireland, a ‘dependent wife’ receives legal aid and does not

14

therefore have to pay for legal expenses of divorce. The need for financial support for sons arose from legal costs, maintenance payments and the expense of maintaining two households, and in the case of most daughters from the fact that they were not in paid employment and had to wait until divorce settlement or maintenance agreement had been reached. The financial implications of the relationship breakdown for sons, particularly those who had been married, were characterised as drastic and unfair:

…I had to [give him] financial [support] as well, because he didn’t have anything the poor thing. He had literally nothing…Whatever he had he put an awful lot of money into the house with her and all that, I mean they started off as any married couple would…he had to…start from scratch again.

(Respondent 4, paternal grandmother)

Legal costs associated with divorce proceedings and gaining access to or (joint) custody of children in some cases had necessitated both short-term and long-term financial assistance to adult sons. In many cases this assistance was, at least on the part of the grandparents, thought of as ‘loans’ that would be paid back at a later, unspecified time, perhaps in order to preserve the dignity of their adult child who had previously been financially independent. In the following case, the acceptance that the ‘loan’ may not be repaid by the son was combined with resentment that the son’s former wife did not bear what the respondent thought would be her fair share of the legal costs:

Grandfather: [W]e paid his mortgage a few times for him…We lent him money a few times and he hadn’t to pay it back to us… We told him if he ever comes good he can give it back to us and if he don’t we’ll do without it.

Grandmother: …the courts really skinned him. She [ex-wife] is getting free legal aid, and she’s just getting everything…

(Respondents 10 and 11, paternal grandparents)

15

Financial support was not limited to cases where the adult child was experiencing financial hardship. Gifts towards house purchase, holidays, cars and other goods and services such as education costs were motivated by the desire to enable the children and grandchildren to maintain a lifestyle that they had become accustomed to, or were expected to reach. These types of outlays were highest in the case of maternal grandparents whose daughters were the custodial parents; in three cases these daughters had received outright gifts of a house purchased for them. These cases corroborate the argument that daughters tend to receive more financial help than sons (Weitzman 1985;

Gerstel 1988). In our sample, the main reasons for the heavy financial support of divorced daughters were the labour market status of mothers (not in paid work either due to high childcare costs or by choice), the failure of some fathers to pay maintenance, and the widespread perception among middle-class people in Ireland that owner-occupied housing is a mark of social respectability.

I’ve given tremendous monetary or financial and infrastructural support. We thought she was going to live in [name of town] when she separated first, so I bought a house in

[town] all of which I paid for myself for her use and she paid rental, a small rental for that.

And she needed a bigger car, the car she had was pretty awful so I paid most of the balance of the between the car she had and the car that would send her children and a couple of friends to the beach and so on.

(Respondent 25, maternal grandfather)

The expenditure on smaller items such as clothing, hobbies and toys for their grandchildren, and occasional large outlays such as holidays, was considerable and went on for several years following divorce or separation:

16

…certainly financially we still help her out. As regards the children’s clothing…even things like books, the [grand]daughter does ballet…we certainly would still financially help her out. Pay for holidays...

(Respondent 26, maternal grandmother)

Childcare Support

Childcare-related support took many different forms, ranging from almost daily provision of childcare to young grandchildren to occasional ‘babysitting’. Not all grandparents were heavily involved in this form of support; some had no or only limited access to their young grandchildren, due to acrimony over access, and others had chosen to limit their involvement for other reasons such as employment. In most cases childcare by grandparents took place alongside strong parental involvement, although our sample did include three custodial grandparents who substituted for parental care.

The most heavily supported group overall were separated sons who had not been married to their former partners; even in the light of this, it is particularly striking that all grandparents who had sons in this category had provided them assistance with childcare following their separation, albeit this assistance was typically confined to the times when the grandchild was visiting the father. This may be related to number of characteristics of the unmarried sons (see also Aquilino

1990), such as their young age, low degree of economic independence, and, for some, the brevity and instability of the partnerships that had resulted in the birth of their children. All respondents with daughters who co-resided with them in the aftermath of the separation had also provided childcare at some point or on an ongoing basis. Crucially, some of these grandparents had taught or were seeking to teach their adult children how to parent. Over time, the son or daughter was able to increase his or her role with the effect that the grandparents were in a position to reduce

17

their involvement. One respondent described the guidance she provided to her son in parenting his own child:

[The son said] that he felt that we [his parents] taught him how to parent, how to play with [his daughter]... I think he…used to nearly panic [when he had to look after his daughter]. [His daughter] loves being around him and I think that's really positive… They have great fun together…So our role would be lessened…and the more it's lessened the better in the sense that the more he takes on.

(Respondent 2, paternal grandmother)

In this case, the decision to become very heavily involved in the care of a young grandchild had also been motivated by the desire to ‘free up’ both the respondent’s adult child and former partner to work without taking recourse to what the grandparents perceived as poor quality kindergartens (daycare). More importantly, however, this respondent had concerns about the fact that the grandchild was not being raised in a stable nuclear family context and felt that they had an important role to play in ensuring that the child was well looked after, educationally stimulated and emotionally secure. Similar to financial and material gifts for adult children who did not strictly speaking need them, this provision of extensive childcare was an attempt to compensate for what the grandparents perceived to be the adverse effects of divorce or separation for the younger generations.

However, at times, the “intrusion” of advice from grandparents created tensions, for example in the following case where the respondent had offered extensive advice on childrearing and personal relationships:

I feel one of my roles is to try and give some guidance and direction but this is resented very much you know.

(Respondent 25, maternal grandfather)

18

Gender differences in the focus and mode of support were evinced through the ‘division of labour’ between grandmothers and grandfathers. Grandmothers tended to ‘specialise’ in emotional support to their adult child, while grandfathers provided more practical support, including childcare which therefore was not exclusively a grandmotherly domain:

…[my daughter] would come up for the weekend with the girls…and [my husband] would play with the girls…[He] is a brilliant grand-dad…[meanwhile] I would talk to [my daughter]…She needed that time…(…) basically it split itself naturally.

The girls played with grand-dad and [my daughter] was able to download information and trauma and stress to me…

(Respondent 24, maternal grandmother)

Emotional support provided by paternal grandfathers took the form of both listening and

“tough love”, enacted rather reluctantly in the following case:

It was terrible…to actually sit down and think about people breaking up, it’s devastating… he [son] has deteriorated, he was devastated…I actually had to say something – you’ve got to get up off your ass, kid. We just had to be strong for him, you know what I mean? And listen to him, listening is very important…I found it very strange because I think it was the first time, and I have three children, it was the first time that I actually had to be very strong and say – right, get up, get on with it – which is not nice.

(Respondent 13, paternal grandfather)

The developmental trajectory of the adult child towards parenthood was not in all cases straightforward. Some of the respondents attributed to their adult child characteristics that were not in keeping with their status as a parent. One grandmother portrayed her adult son as being like a big brother to his own child, and herself as the mother to both of them:

19

I mean they are sitting there and they’re arguing over cartoons or a football match, you know, that kind of thing. So I’d be the mother, we’ll say, in the background of it.

(Respondent 12, paternal grandmother)

In other cases, the respondents felt that the behaviour of their adult children, while in many ways corresponding to that of a responsible parent, still left a lot to be desired and had to be ‘patched up’ by them due to the adult child’s failure to pull his weight as a parent and as a member of the household:

…He tends not…to pick up after [grandchild]…her clothes…there's a frustration around it.

(Respondent 15, paternal grandmother)

Despite these irritations the grandmother quoted above did not think that the quality of her relationship with her son had deteriorated as a result of co-residence: feelings of solidarity outweighed conflict.

Extensive involvement in childcare and in acting as the ‘bridge’ between the separated parents did in some cases spill over into excessive responsibility and reliance on the grandparents, especially, in our sample, paternal grandmothers. This respondent felt that her son’s time with his children had come to revolve around her and to depend on her to an extent that over time had become burdensome:

…I started taking responsibility for his relationship with his children…Because it was like “well ma, we’ll be down on Sunday”, and so I had to be there on Sunday no matter what happened…I was making the dinners and he wasn’t doing anything…he didn’t go [out] with them…so the highlight of the [children’s] visits

[to their father] became that they came to see me…

(Respondent 16, paternal grandmother)

20

Over time, this extensive involvement had become burdensome for the grandmother, and the excessive reliance on her to facilitate contact between her sons and their children had resulted in conflict and a vicious circle of accusations, guilt, and deteriorating quality of relationships.

However, generally respondents saw their ’bridging’ role between the separated parents as a pragmatic approach to maintaining positive relations, particularly with the grandchildren:

I mean the bottom line in the whole conciliatory thing was our concern for the welfare of the grandchild. This was kind of necessary. I don't know... I think we're sort of reasonably conciliatory.

(Respondent 3, paternal grandfather)

Co-Residency

Financial difficulties, the sale of the family home or relinquishing it to the former partner or spouse were among the reasons why several grandparents had accommodated their son or daughter for varying lengths of time following separation. All paternal grandparents whose son had not been married experienced a spell of co-residence with their son following the breakup.

This in turn is partly linked to the fact that public housing in Ireland is more easily accessed by separated or divorced mothers who have custody of children and to a number of characteristics of the unmarried sons (such as young age, low degree of economic independence). Co-residence easily spilled over into extensive involvement of the grandparent(s) with the trauma and stress that accompanies separation and divorce, especially in cases where there was on-going conflict between the separating couple:

21

…I think he really leant on me a lot…I had three pretty awful years when he came back to live me. We never knew what brick that she [son’s ex-wife] was going to throw at him...

(Respondent 14, paternal grandmother)

Most respondents stated that co-residence with their adult child was far from an ideal option, and one that was imposed on both parties due to limited financial means, short-term lack of alternative housing, an increase in child care responsibilities, or all of these. For some paternal grandparents, there was the additional consideration of being in a position to offer a stable place where the son could bring his child(ren). While the grandmother quoted below had offered this arrangement initially as a short-term solution, it had become a long-term situation that caused considerable stress and tension for her. It is evident from the quote below that this grandmother was torn between the sense of duty towards her son and grandchild, and the desire to scale back her involvement:

…I don't think he should be living at home with his parents…He's a hard one to live with because he's very quiet, very withdrawn…he tends to have mood swings…drinks too much...But he is extremely attentive to [his daughter] and…spends good quality time with her…I would prefer if he was living [in] a home of his own that was suitable enough to bring [his daughter]…friends of his had said he could have a bed in their home and I said look you have to think of

[granddaughter], you have to have somewhere stable…for her alone you should come back and it took coaxing and he said okay I'll come back for a couple of months and Jesus he's still there…

(Respondent 15, grandmother, unmarried son)

Legal and Other Advisory Supports

22

Eight grandparents had become very closely involved in assisting their adult child with the legal proceedings associated with divorce or with gaining access to children. In the following case this involvement was motivated by the perception that the daughter lacked the skills and resources required to negotiate the legal process in an optimal way:

I took up being correspondent between the lawyers and my daughter…I would type the letters, fax through the details and keep pressure on the lawyers and obviously attend any meetings with barristers, with solicitors, attending at the court.

(Respondent 24, grandmother, married daughter)

There was a greater propensity among paternal grandparents to become involved in the provision of legal advice and assistance, reflecting the greater likelihood of sons to feel aggrieved by some parts of the legal process and decisions. In the following case, provision of assistance with legal matters pertaining to her son’s access to his child had led the respondent to take time off work.

The nature of the assistance in this case was not very technical, but rather related to the need to be present at meetings, and to the inability of the son, both practically and emotionally, to take time off work and to become embroiled in the process. This grandmother also felt that in providing assistance to her son, she was compensating for the absence of more formal sources of assistance:

Respondent: There just literally is no help for the guy…at one stage I had to take…loads of hours off [work] while we were waiting to get the court case sorted.

Interviewer: Okay. Why did you have to take the time off?

Respondent: Because I needed [son’s name] to keep [his] job, to keep his head...he was going through a very bad time.

(Respondent 12, grandmother, unmarried son)

In a small number of cases grandparents also gave assistance with claims, administration and other paper work after the divorce or separation. One respondent had invested considerable time

23

and energies into ‘lobbying’ (successfully) for public housing for her son, motivated by the desire to ensure that he had his own residence where the grandchildren could also spend time.

The grandparents in our study had in many cases reflected extensively on their role within the family. All were willing to provide extensive support but also sought to set their involvement at a level that they deemed manageable and appropriate. When initially called upon to respond to the distress and needs (for money, housing, emotional support, childcare, advice) generated by their adult children’s relationship breakdown, the respondents had responded largely on the terms of their children and grandchildren. Following their generous response to the crisis period in their adult children’s lives, grandparents usually sought to gain greater control over their role and adjusted their involvement to a level that they regarded as manageable and suitable, and also thought it important to encourage their adult children to regain control over their own lives.

Nonetheless, extensive involvement out of line with the respondents’ wishes did sometimes continue, giving rise to varying degrees of exasperation and even resentment which in turn could lead to more determined attempts to regain control of their level of involvement. This pattern was particularly strongly evident in relation to childcare supports provided by paternal grandparents who struggled more than maternal grandparents to limit their involvement and felt that they had to continue their involvement in order to secure continued access to their grandchildren. This maternal grandmother had become aware of the negative consequences of excessive involvement in co-parenting and decided to take action to guard against the danger of such involvement:

…for a while I felt I was trying to compensate for their lack of parenting and now

I’m not doing that any longer. I’ve withdrawn from that and I think the danger is that you would get hooked into that role and stay with it.

(Respondent 18, grandmother, married daughter)

24

However, resolutions against excessive involvement were not always a realistic option for grandparents who co-resided with their adult child or otherwise acted as the indispensable

‘bridge’ between their children and grandchildren.

Discussion

This article is motivated by the paucity of literature that examines divorce and separation from the point of view of the divorced or separated adults’ parents. In the light of the findings outlined above, the behavior of grandparents in the context of their adult children’s relationship breakdown is characterized by compensation (for losses the children and grandchildren were perceived to endure) on the one hand and the setting of boundaries to their own involvement on the other hand. These responses are explained by the feelings of solidarity towards adult children that tended to increase during and after the latter’s relationship breakdown, and by the fact that the support needs of adult children often exceeded, in duration and/or intensity, what the respondents considered appropriate levels of intergenerational support, giving rise to ambivalence .

These findings are consistent with both the solidarity and ambivalence theories. In line with

Bengtson et al (2002), we argue that these frameworks are not irreconcilable but rather serve the purpose of explaining different stages and aspects of human relationships: ‘each shows us something…about how family members attempt to stay together, what pulls them apart, and how their negotiate their differences’ (Bengtson et al. 2002: 575).

Older adults were compensating for a range of perceived losses in their adult children’s and grandchildren’s lives. These included material losses and setbacks associated with the loss of the family breadwinner (for daughters) or high expenses associated with legal proceedings and maintenance payments (for sons). Emotional setbacks that the parents sought to compensate for

25

included the perception that their children had been mistreated by their former spouse or partner, was the victim in the relationship, and was emotionally vulnerable. The resulting feelings of affective solidarity, protective parenting style and unstinting support of their adult children practiced by many parents in the post-separation scenario meant that some reverted to earlier

‘parenting’ roles (Leahy Johnson 1988). We argue that these behaviours are different forms of compensation that older adults feel their adult children need in a situation where the basic parameters of their lives have been radically shifted. The fact that the grandparents recounted strong links between increased provision of support and their increased feelings of closeness with their adult children (both dimensions of intergenerational solidarity) supports the argument that parents feel intergenerational solidarity, i.e. a strong normative obligation to provide help

(Silverstein and Bengtson 1997). This preceded feelings of conflict and ambivalence in the respondents’ accounts, hence lending credence to the argument of Bengtson et al (2002) about the primacy of solidarity in intergenerational relations. Furthermore, in response to the question posed by Silverstein and Giarrusso (2010, p. 1050), ‘whether the discomfiting nature of mixed feelings has positive or negative implications for the subject or object of ambivalence’, we argue that the implications were predominantly (but certainly not exclusively) positive for the subjects of ambivalence (grandparents) in our sample.

The hypothesis that divorce in the younger generation can lead to more frequent intergenerational interaction and increased supports has been proposed by Ahrons and Bowman (1982) and tested by Sarkisian and Gerstel (2008); the findings reported here give further credence and grounds for theorizing and analyzing these positive impacts of divorce on inter-generational relations. In contrast to arguments advanced by for instance Kaufman and Uhlenberg (1998), our research indicates that positive effects, from the perspective of parents, can ensue in the aftermath of divorce or separation in the younger generation in the form of closer inter-generational ties. Our research leads us to hypothesise that significant positive impacts can also ensue from adult

26

children’s negative life experiences such as divorce or separation, and that these can co-exist with negative impacts; these impacts should be the subject of further qualitative and quantitative research.

Support provision was largely directed by adult children’s and grandchildren’s needs, but grandparents also sought to bring the extent of support provision within acceptable parameters i.e. to set boundaries to their involvement. From the perspective of grandparents, support provision generally had a positive impact on the parent-adult child relationship except where the grandparent was not able to set these boundaries i.e. to calibrate involvement to a level s/he deemed manageable, for instance where extensive involvement in childcare or co-residence continued beyond the parent’s expectations. Overall, however, there was little evidence of lasting conflict between the parental and adult child generations in our sample which leads us to argue that, at least from the parents’ perspective, these relationships are primarily characterized by solidarity. However, the challenges faced by our respondents may also serve to highlight the

“complexities of relationships that stem from the inherent contradictions of social life” (Connidis

2009, p. 140). Reflecting the solidarity, conflict and ambivalence frameworks, shifts in family structure brought about by divorce and separation (structural solidarity), are related to shifts in interaction (associational solidarity) and provision of support (functional solidarity) as well as conflict.

Our respondents’ endeavors to both help their children and grandchildren but also to set boundaries, to calibrate their involvement to a level that was manageable to them, are to some extent captured by the concept of ambivalence. This concept does not fully encapsulate the complex behaviours and emotions the respondents in our study recounted but it does go some way towards making sense of them, especially as the ambivalence-generating aspects of parentchild relationships identified by Luescher and Pillemer (1998, p. 417) were all present, namely

27

solidarity, the tension between autonomy and dependence, and conflicting norms regarding intergenerational relations.

The contexts where feelings of ambivalence were particularly acute were childcare support that proved more extensive or of longer duration than anticipated; and coresidence that lasted longer than expected.

As with all research, the study suffered from a number of limitations, which readers should bear in mind while considering the findings. As all respondents within our sample were grandparents, we are not in a position to discuss possible divergence between their experiences and the experiences of older adults in situations where grandchildren are not present. This was the first study of grandparenting in the context or divorce and separation in Ireland and we wanted to draw a heterogeneous sample in order to get an understanding of the diversity of experiences of grandparents. However, the method of self-selection used for the study may mean that some of the individuals interviewed were “outlier cases”. For instance, it is possible that individuals interviewed wished to participate because they were experiencing a greater number of difficulties as a result of their child’s divorce or separation than may have been the case we had used a random sampling technique. Due to their greater propensity to come forward for studies on topics relating to family life, women were in clear majority in the study (23 out of 31); this means that a small number of men (eight) yielded the data on men’s experiences; a larger sample of men would have given us a better understanding of the diversity of grandfathers’ experiences. Due to budgetary restrictions and timeframe available, we were able to conduct interviews at one point in time only, hence making longitudinal analysis impossible. We had to terminate interviewing before new themes ceased to arise in the interviews (i.e. interviewing did not reach the saturation point).

Unlike some other studies of the impact of divorce in three-generational contexts that interviewed members of two or three generations (see for instance Connidis 2003), we approached the topic

28

from the perspective of grandparents only. This is a limitation: we were not able to compare the findings with the younger generation’s responses. However, the explicit purpose of our research was to gain a deeper understanding of the interpretations and experiences of older adults : the findings represent the views and opinions of grandparents and have not been corroborated by or contrasted with those of their adult children. The fact that their adult children were not interviewed arguably meant that the parents felt less restricted in their responses, i.e. that social desirability bias and self-enhancement were reduced. Nonetheless, readers are advised to bear in mind the discrepancy in the reports of parent-child dyads that is well-established in the literature

(Mandemakers and Dykstra 2008; Shapiro 2004).

An emphasis on the care needs of older adults in the academic literature has meant that their contributions to the multigenerational family are frequently overlooked. Consistent with research on downward (from older to younger) provision of intergenerational support, especially at times of family crisis, our findings corroborate the importance of grandparents in providing family stability. Further research is necessary to acquire an improved understanding of what factors influence support provision by parents to their divorced or separated adult children. Future research should explore the gendered nature of support provision in the aftermath of divorce or separation; we also need to better understand the process of calibrating supports over time; who makes choices and uses their agency (and how) and who acquiesces to their adult children’s requests; what exactly motivates and drives support provision: adult children’s needs or their parents’ perceptions of what they need? Finally, it is also necessary to examine the reciprocal and long-term implications of grandparental assistance on future intergenerational transfers. Does the provision of extensive assistance in the aftermath of separation strengthen family ties in the long run and are adult children who were the recipients of substantial support post divorce/separation more likely to provide support to their parents in later years? In the light of the possible long-term

29

ramifications of intergenerational assistance brought about by changing partnership and family forms, the importance of these questions cannot be overstated.

30

References

Ahrons, C. R., & Bowman, M. E. (1982). Changes in family relationships following divorce of adult child: Grandmothers' perceptions. Journal of Divorce , 5, 49-68.

Amato, P. and Cheadle, J. (2005) The Long Reach of Divorce: Divorce and child well-being across three generations. Journal of Marriage and Family (67), 191-135.

Aquilino, W.S. (1009) The Likelihood of Parent-Adult Child Coresidence: Effects of Family

Structure and Parental Characteristics. Journal of Marriage and the Family 52(2): 405-419.

Bengtson, V. L., Biblarz, T. J., & Roberts, R. E. L. (2002). How families still matter: A longitudinal study of youth in two generations.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bengtson, V., Giarrusso, R., Mabry, J. B. and Silverstein, M. (2002) Solidarity, Conflict, and

Ambivalence: Complementary or Competing Perspectives on Intergenerational Relationships?

Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 568-576.

Bengtson, V.L. (2001) The Burgess Award Lecture: Beyond the Nuclear Family: The Increasing

Importance of Multigenerational Bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family 63: 1-16.

Bengtson, V.L. and Schrader, S.S. (1982) Parent-Child Relations. In: Mangen, D.J. and Peterson,

W.A. (Eds.) Handbook of Research Instruments in Social Gerontology , Vol 11. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 115-185.

Berger, F. and Fend, H. (2005) Continuity and Change in Affective Parent-Child Relationship from Adolescence to Adulthood.

Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung and Sozialisation

25(1):

8-31.

Connidis, I.A. (2003) Divorce and union dissolution: Reverberations over three generations.

Canadian Journal of Aging 22(4): 353-368.

Connidis, I.A. (2009) Family ties and aging (Second Edition). Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks,

California.

Connidis, I.A. and McMullin, J.A. (2002) Ambivalence, Family Ties, and Doing Sociology.

Journal of Marriage and Family 64(3): 594-601.

Cooney,T.M. and Uhlenberg, P. (1990) The role of divorce in men's relations with their adult children after mid-life. Journal of Marriage and the Family 52: 677-688.

Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2008) Basic of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for

Developing Grounded Theory (Third Edition). Sage: London.

Daatland, S.O. (2007) Marital History and Intergenerational Solidarity: The Impact of Divorce and Unmarried Cohabitation. Journal of Social Issues 63(4): 809-825.

Dykstra, P.A. (1997) The effects of divorce on intergenerational exchanges in families.

Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences 33(2): 77-92.

Eggebeen, D.J. (2005) Cohabitation and exchanges of support. Social Forces 83: 1097-1110.

31

Gerstel, N. (1988) Divorce and Kin Ties: The Importance of Gender. Journal of Marriage and

Family 50: 209-219.

Giarrusso, R., Silverstein, M., Gans, D. and Bengtson, V.L. (2005) Ageing Parents and Adult

Children: New Perspectives on Intergenerational Relationships. In: Johnson, M.L. (Ed.) The

Cambridge Handbook of Age and Ageing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 413-421.

Glaser, K., Stuchbury, R., Tomassini, C. and Askham, J. (2008) The Long-Term Consequences of Partnership Dissolution for Support in Later life in the United Kingdom. Ageing & Society

28(3): 329-351.

Gray, C.A and Geron, S.M. (1995) The Other Sorrow of Divorce: The Effects on Grandparents

When Their Adult Children Divorce. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 23(3-4): 139-159.

Greenberg, J.S. and Becker, M. (1988) ‘Aging parents as family resources’

Gerontologist 28:

786-791.

Hagestad, G.O. (2006) ‘Transfers between grandparents and grandchildren: the importance of taking a three-generation persepctive’, Zeitschrift Fur Familienforschung 18:. 315-332.

Hoffman, C.D. and Ledford, D.K. (1995) Adult Children of Divorce: Relationships with their

Mothers and Fathers Prior to, following Parental Separation, and Currently. Journal of Divorce &

Remarriage 24(3-4): 41-57.

Johnson, E. and Vinick, B.H. (1982) ‘Support of the parent when adult son or daughter divorces’,

Journal of Divorce 5: 69-77.

Kaufman, G. and Uhlenberg, P. (1998) Effects of Life Course Transitions on the Quality of

Relationships Between Adult Children and Their Parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family

60(4): 924-938.

LaRossa, R. (2005) ‘Grounded Theory Methods and Qualitative Family Research’,

Journal of

Marriage and Family 67: 837-857.

Leahy Johnson, C. (1988) Post-divorce reorganization of relationships between divorcing children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family 50: 221-231.

Lin, I-Fen (2008) Consequences of Parental Divorce For Adult Children’s Support of their Frail

Parents. Journal of Marriage and Family 70: 113-28.

Luescher, K. and Pillemer, K. (1998) Intergenerational Ambivalence: A New Approach to the

Study of Parent-Child Relations in Later Life. Journal of Marriage and Family 60: 413-425.

Lunn, P., Fahey, T. and Hannan, C. (2009) Family Figures: Family Dynamics and Family Types in Ireland, 1986-2006.

Dublin: The Economic and Social Research Institute.

Lye, D. (1996) Adult Child-Parent Relationships. Annual Review of Sociology, 22: 79-102.

Mandemakers,J.J, Dykstra, P.A. (2008) Discrepancies in Parent’s and Adult Child’s Reports of

Support and Contact. Journal of Marriage and Family 70(2): 495-506.

Mancini, J. A. and Bliezner, R. (1989) Aging Parents and Adult Children: Research Themes in

Intergenerational Relations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 51: 275-290.

32

Nock, S. (1995) A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family

Issues 16: 53-76.

Pearson, J.L. (1993) Parents’ Reactions to their Children’s Separation and Divorce at Two and

Four Years – Parent Gender and Grandparent Status. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 20(3-4):

25-43.

Pillemer, Karl and Suitor (1991) ‘Will I Ever Escape My Child’s Problems?’ Effect of Adult

Children’s Problems on Elderly Parents.

Journal of Marriage and Family 53(3): 585-94.

Pillemer, Karl, and J. Jill Suitor. (2002) Explaining Mothers Ambivalence Toward Their Adult

Children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64: 602-613.

Pillemer, Karl, J. Jill Suitor, Steven Mock, Myra Sabir, and Jori Sechrist. (2007) "Capturing the

Complexity of Intergenerational Relations: Exploring Ambivalence within Later-Life Families."

Journal of Social Issues, 63: 775-791

Rossi, A.S. and Rossi, P.H. (1990) Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations Across the Life

Course. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Sarkisian, Natalia and Gerstel. Naomi (2008) ‘Till Marriage Do Us Part: Adult Children’s

Relationships with their Parents’, Journal of Marriage and Family 70(May): 360-376.

Shapiro, A. (2004). Revisiting the generation gap: Exploring the relationships of parent/adultchild dyads. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 58: 127 – 146.

Silverstein, M. and Giarrusso, R. (2010) Ageing and Family Life: A Decade Review. Journal of

Marriage and Family (72) 1039-58.

Silverstein, M., & Bengtson, V. L. (1997). Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child-parent relationships in American families. American Journal of Sociology , 103, 429-460.

Spanier, G.B. and Hanson, S. (1982) The role of extended kin in the adjustment to marital separation. Journal of Divorce 5: 33-48.

Spitze, G., Logan, J.R., Dean, G. and Zerger, S. (1994) Adult Children’s Divorce and

Intergenerational Relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family 56(2): 279-293.

Stuifbergen, M.C., Van Delden, J.J.M. and Dykstra, P.A. (2008) The Implications of Today’s

Family Structures for Support Giving to Older Parents. Ageing & Society 28(3): 413-434.

Sullivan, M. (1986) Ethnographic research on young black fathers and parenting: Implications for Public Policy. Vera Institute for Justice.

Tomassini, C., Kalogirou, S., Grundy, E., Fokkema, T., Martikainen, P, Broese van Groenou, M and Karisto (2004) Contacts between elderly parents and their children in four European countries: current patterns and future prospects. European Journal of Ageing, (1) 1, 54-63.

Weitzman, L.J. (1985) The Divorce Revolution. The Unexpected Social and Economic

Consequences for Women and Children in America. Free Press: New York.

33