Developing Your Research Potential Lecture Series 2011

advertisement

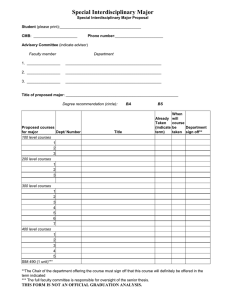

F. Ellen Netting, Ph.D. Professor & Samuel S. Wurtzel Endowed Chair VCU School of Social Work enetting@vcu.edu Developing Your Research Potential Lecture Series 2011 Managing Interdisciplinary Research: Opportunities and Challenges April 5, 2011 10:00-11:30 Student Commons, Commonwealth Ballroom A Collaborating Across Units/Organizations Interdisciplinary collaborations across units within the same university Interdisciplinary or interprofessional collaborations across different universities Community-university partnerships What is Collaboration? Those who want to successfully broker intricate partnerships are advised to Athink systematically and act interpersonally.@ Effective communication should balance the desire to cultivate optimal interpersonal relations with the efficiency required for expedient goal achievement. Valuing the importance of relationships, however, cannot be underestimated. Without attention to interpersonal details, there is little hope of maintaining communication among partners and sustaining those relationships (Welleford et al, 2004). Ede and Lundsford (1990) contend that only through a mutual integration of theory and practice can one resist the powerful seduction of oversimplifying solutions, and collaboration is the processing of this integration and coming to some agreement about it. Hess and Mullen (1995) indicate that “to collaborate is to labor together” (p. 5), whereas Wheatley and Kellner-Rogers (1996) would likely frame collaboration differently -- as actually playing together. “Life is creative. It explores itself through play, intent on discovering what’s possible. Can we bring this creative play of the world into our lives in organizations?” (p. 20). Perhaps these statements reveal how paradoxical collaboration truly is, for the frame one brings to the collaborative relationship surely influences how one views the process – as labor (work) or as play. We believe that it is not an “either-or,” but that collaboration is both. Therefore, we define collaboration as a process in which two or more persons work and play together to achieve some result or create some product in which they are jointly invested, about which they care enough to pool their strengths. These persons may be from the same or different fields, disciplines, and/or professions (Macduff & Netting, 2000). Transactional Considerations Structural – defining roles, setting up overriding structures, determining accountabilities Cultural – recognizing differences in values and assumptions Logistical – identifying and following through on specific activities 1 Relational – attending to interpersonal connections, building trust, working/playing together Points to Consider in Managing Interdisciplinary Research (This checklist is from Ross et al, 2010) Finding or Forming the Community Partner Are the prospective research participants members of an identifiable group with whom the academic researchers can partner? Is the group structured (an established community) or is it unstructured? Does the group have designated leadership (structured group) or can leadership be created, either externally or internally (by group self organization)? Is/are the community leader(s) responsive and inclusive to the needs of the group that they represent? Do/does the leader(s) understand the requirements of the research project and the risks and benefits for his/her specific community? Are the community leaders respected by the community and the academic researchers? Is there a community-based organization that provides services to the group for whom the research agenda is consistent with its mission? Is/are the leaders/community-based organization willing to learn/acquire knowledge that will be beneficial to the group that it/they represent(s)? (Ross, 2010, p. 22) Finding an Academic Researcher Partner Does the academic researcher have the skills, experience, and resources necessary for the specific research project? Does the academic researcher seem willing to collaborate and respect the agency of the community? Is the researcher committed to long-term relationships with community partners? Is the researcher willing to pursue the advocacy and policy issues that emanate from the research? If not, can others help in these roles? Does the academic researcher have some degree of institutional commitment for promoting successful academic-community partnerships? (Ross, 2010, pp. 22-23) Agenda Setting and Developing a Joint Work Plan Has there been adequate dialog to ensure that the health priorities of the partnership reflect the community’s needs? Does the academic researcher have the skills and interest to address the research needs of the community? Is funding available for this type of research? If funding is not available for a particular research priority, are the academic researcher and community willing to pursue other projects and attempt to procure funds for addressing this top priority at a later stage? (Ross, 2010, p. 23) Research Design and Implementation Have the possible results of the research been anticipated and discussed? 2 Do conflicts of interest (COI) exist? Is there a COI management plan that is acceptable to all? What components of the research are modifiable, and have the interests of both parties been explored? What components of the research are non-negotiable and are these constraints acceptable to both parties? Will the data be usable for future research projects? Has an agreement been reached about who has access to, and control of, data after the research is completed? Has an agreement been reached about authorship? Has an agreement been reached about intellectual property? (Ross, 2010, p. 24) Applying for Funding Who is eligible to apply for funding as principal investigator(s)? Who will apply for funding as principal investigator? Does the funder have an appreciation for the degree of collaboration intended by the research partners? If each partner will manage part of the funds, does each partner possess adequate expertise in managing grant funds and the resources and expertise necessary to fulfill reporting requirements?(Ross, 2010, p. 25) The Consent Process for Individuals and Groups What are the risks of participating in the research project for the individual and the community? What are the risks to non-participating community members? What are the possible risks to agency or individuals from the group’s involvement? What are the possible benefits of participating in the research for the individual and the community? Is formal community consent appropriate, considering the history, established structure, and cohesiveness of the group? If formal community consent is not needed, how has the group or community expressed its endorsement of the research project? If formal community consent or informal endorsement is given, have adequate measures been taken to ensure that individual members understand that their participation is voluntary? Have research partners developed an MOU that signifies agreement by all parties to proceed? (Ross, 2010, p.25) Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Dissemination Does the community seek any restrictions on data reporting and dissemination? Has an agreement been reached as to how culturally sensitive results, or results with potential negative implications for a community, will be framed and disseminated? Will the data be usable for future research projects? And who will control this access? Will the academic researchers provide some training on data analysis and journal publication? How should the community partners be listed in publications? (Ross, 2010, p. 28) 3 After the Project What are the short-term benefits and long-term benefits that the community receives from research collaboration? What short-term benefits and long-term benefits do the academic researchers receive from research collaboration? Is the research project part of larger programmatic research within the academic institution that requires sustained involvement with the community, or is it a self-limited project of defined duration? Have the academic researcher and the community/group/leadership discussed the implications of the project’s completion – both positive and negative? Have any plans or promises been made to preserve the relationships, infrastructure, and benefits developed in the community after the life of the project? (Ross, 2010, p. 28) Dissemination: Negotiate in the Beginning a Flexible Plan Without dissemination, no one can benefit from what you’ve learned . . . . . . A. Assessing Your Collaborators’ Motivations & Writing Styles MOTIVATIONS What motivates your writing? What assumptions to you bring to the process? STYLES -- Individualistic ---- Collaborative -- Like to Write Every Day --- Like to have Large Clumps of Time -- Can Work under any Condition -- Has to have a Things in Order -- Enjoys the Process -- Finds the Process Burdensome -- Looks forward to the Process -- Dreads the Process -- Can Sit for Hours Composing -- Finds Self in Front of the Refrigerator Every Half Hour or Checking email -- Needs to talk about ideas with others -- Likes to mull over Topic Alone -- Starts at the Beginning -- Starts in the Middle -- Works from an Outline -- Never Uses an Outline -- Can Sit at the Computer with a Co-Author -- Wants to Write Alone -- Finds Writing Easy -- Finds Writing Hard -- Other Considerations? B. Considering Your Collaborative Experiences and Expectations (Apgar & Congress, 2005) EXPERIENCES What has been your experience with co-authors or collaborators? How have these experiences (or experiences shared by others) shaped your views on collaboration? How do your experiences vary from those of your collaborators/partners? EXPECTATIONS 4 -- What expectations do collaborators bring to the writing process? - about timelines? - about what a first draft means? - about order of authorship? - about first authorship? - about single authorship? C. Negotiating Collaborative Writing Products within Context (Netting & NicholsCasebolt, 1997) GUIDELINES Have you negotiated expectations upfront? Are you flexible enough to change as the process unfolds? Do you acknowledge people who have contributed? Do you know when to accept or negotiate a co-authorship? CONTEXT: Unwritten rules, myths & norms Academic B Community Discipline B Profession Tenure and promotion considerations What is the definition of scholarship in this context? Peer review in-house part of culture B you=re on your own What is required? What is expected? B The importance of single authorship/collaboration B The importance of first authorship B Mainline professional journals versus interdisciplinary journals B Journals versus books B Numbers of publications B Refereed publications B Number of citations B Placement of publications on your CV B Others? D. Targeting audiences & journals AUDIENCES Who needs to hear what you have to say? Do you need to target multiple audiences (i.e. practitioner, research, disciplinary, interdisciplinary, popular, or other type group)? JOURNALS What journals target your intended audiences? If there are several, which are considered the best journals to get to specific groups? Do you have backup journals in mind? E. Preparing & submitting manuscripts OBTAINING WRITTEN GUIDELINES Do you have the guidelines for authors? 5 Have you conformed to the style? ASSESSING WHAT THIS JOURNAL PUBLISHES Is this a refereed journal? What kinds of articles has this journal published recently and what does that tell you about what they are accepting? (look at Table of Contents) Are you citing appropriate articles that have already been published in this journal? (Remember that the authors of those articles may be your reviewers.) SUBMITTING THE MANUSCRIPT What do you expect the lead author to do? Who will be the corresponding author? If you need to revise, have you carefully responded to all comments, even those with which you do not agree or cannot make? If rejected outright, have you decided whether to revise or whether to turn it around to another journal "as is" (and the implications of either)? If encouraged to resubmit, have you carefully inventoried every reviewers' comments and responded accordingly? Selected References Anderson, J. A. (2001). The collaborative research process in complex human service agencies: Identifying and responding to organizational constraints. Administration in Social Work, 25(4), 1-19. Apgar, D. H., & Congress, E. (2005). Authorship credit: A national study of social work educators= beliefs. Journal of Social Work Education, 41(1), 101-112. Bayne-Smith, M., Mizrahi, T., & Garcia, M. (2008). Interdisciplinary community collaboration: Perspectives of community practitioners on successful strategies. Journal of Community Practice, 16(3), 249-269. Bronstein, L. R. (2002). Index of interdisciplinary collaboration. Social Work Research, 26(2), 113-123. Butterfield, A. K. J., & Soska, T. M. (2004). University-community partnerships: An introduction. Journal of Community Practice, 12(3/4), 1-11. Ede, L. & Lunsford, A. (1990). Singular texts: plural authors: perspectives on collaborative writing. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. Fawcett, S. B., Paine-Andrews, A., Francisco, V. T., & Schultz, J. A. (2000). A model memorandum of collaboration: A proposal. Public Health Reports, 115(2/3), 174-179. Foster, M.K. & Meinhard, A.G. (2002). A regression model explaining predisposition to collaborate. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31(4), 549-564. 6 Gray, B. & Wood, D.J. (1991). Collaborative alliances: Moving from practice to theory. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(1), 3-22. Haines, V. A., Godley, J., & Penelope, H. (2011). Understanding interdisciplinary collaborations as social networks. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 1-11. Hess, P. M., & Mullen, E. J. (Eds.) (1996). Practitioner-researcher partnerships: Building knowledge from, in, and for practice. Washington, D.C.: National Association of Social Workers Press. Huber, R., Borders, K., Netting, F.E., & Kautz, J.R. (1997). To empower with meaningful data: Lessons learned in building an alliance between researchers and long term care ombudsmen. Journal of Community Practice, 4(4), 81-101. Kulage, K. M., Larson, E. L., & Begg, M.D. (2011). Sharing facilities and administrative cost recovery to facilitate interdisciplinary research. Academic Medicine, 86(3), 394-401. Macduff, N. & Netting, F. E. (March 2000). Lessons learned from a practitioner-academician collaboration. Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 46-60. Maurrasse, D. J. (2002). Higher education-community partnerships: Assessing progress in the field. Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31, 131-139. Netting, F. E., & Nichols-Casebolt, A. (1997). Authorship and collaboration: Preparing for the next generation of social work scholars. Journal of Social Work Education, 33(3), 555564. Pierce, L.R. & Ball, J. (2000). How to conduct a literature search on the topic of interdisciplinary health care research. National Academies of Practice Forum, 2(1), 5557. Ross, L. F., Loup, A., Nelson, R. M., Botkin, J. R., Kost, R., Smith, G. R., Gehlert, S. (2010). The challenge of collaboration for academic and community partners in a research partnership: Points to consider. Journal of Empirical Resaerch on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal, 5(1), 19-32. Powell, J., Dosser, D., Handron, D., McCammon, S., Temkin, M.E., & Kaufman, M. (1999). Challenges of interdisciplinary collaboration: A faculty consortium=s initial attempts to model collaborative practice. Journal of Community Practice, 6(2), 27-48. Rice, A. H. (2000). Interdisciplinary collaboration in health care: education, practice, and research. National Academies of Practice Forum, 2(1), 59-73. Welleford, A., Parham, I.A., Coogle, C., Netting, F.E., Burke, L. P. & Boling, P. (June 2005). University-community Partnerships in the Development of a Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training Certificate. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 24(3), 21-25. Wheatley, M. J. & Kellner-Rogers, M. (1996). A simpler way. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. 7