How to Make an Effective, Professional Research Presentation Platform & Poster Presentations

advertisement

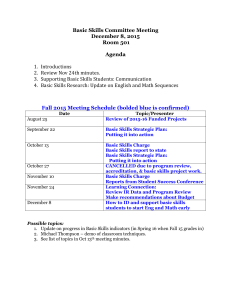

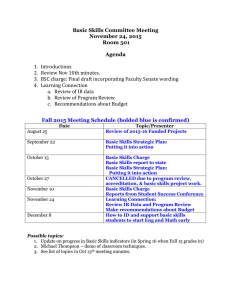

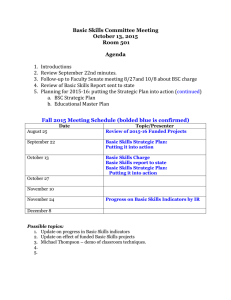

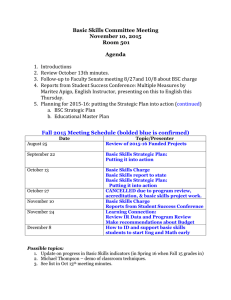

How to Make an Effective, Professional Research Presentation Platform & Poster Presentations John Stevenson, PT, PhD Associate Dean, Graduate Studies Sept 12th, 2015 Presentation Models for Professional Meetings Platform presentation (15-min cycle; 20-min) ◦ 12 min for presentation followed by < 3 min Q & A SSD format ◦ Poster presentation (5’ x 7’ or 4’ x 6’ areas) SSD/MERC format Symposia Longer times (60-90 min) More lecture style Panel Discussions Introductions, followed by debatable premise or question Participants interact in discussion; take Q & A in last third or quarter Summary Platform (oral) Presentation Elements Introduction of title and author(s) by moderator Make sure moderator knows how to pronounce your name(s)! Body of talk, starting with title slide Audiovisuals (Powerpoint or video) Use of pointer (laser or light), if effective Author response to questions and/or comments from attendees Outline of Presentation Title slide with author name(s) Background – 1-2 slides ◦ Slide(s) that introduce the audience to the relevance or application of the project May use pictures to complement points Purpose – 1 slide ◦ The primary purpose of the study or case report, stated as research hypothesis or central question of the study or case Outline of Presentation Description of Methodology – 3-5 slides ◦ Subject description with inclusion/exclusion criteria ◦ Sampling technique with randomization method used, if applicable ◦ Description of instrumentation used to measure or assess variables of interest Equipment pictures really help here! Provide sense of validity and reliability Description of dependent variable(s) measured ◦ Research design used for study ◦ Statistical or data analysis techniques used Examples & Ideas Research about use of trust in execution of golf skills Example slide 1 Measuring Trust in the Performance of Golf Skills Mike Brossman, SPT Doug Elliott, SPT Mark Liley, SPT Physical Therapy Program College of Health Professions Example slide 2 “When I trusted my swing, I hit it perfect. When I tried to steer it just a touch or bow it down and just try to get it in play, I didn’t hit the ball straight at all. I’m hitting it well with my irons, hitting it well at the range, hitting it well when I just step up and trust it. I’ve just got to do that more often.” ◦ Tiger Woods, 2003 U.S. Open Example slide 3 Methodology: Subjects 28 golfers in the Professional Golf Management Program at Ferris State University, Big Rapids, MI Average age of 21 years, 11 years of golf experience, USGA handicap < 10.0 Highly motivated to improve putting performance, received a 3-hr Trust training and drills program, used their own equipment for testing Fundamental Skill Components that lead to Trust Concentration – Focusing on the process Confidence – Belief that if you execute your routine, success will follow Composure – Conviction that your skills will not erode under pressure or stress Example slide 4 Example slide 5 Putting Analysis System -+ Trajectory Velocity Outline of Presentation Results – 3-4 slides ◦ Use graphed results to compare or contrast numerical results ◦ Minimize use of numerical tables; avoid plentiful use – boring! ◦ Consider summary findings slide Discussion – 1-2 slides ◦ Relate how findings impact literature, theory, practice ◦ Impact of your study results Conclusion – 1 slide ◦ What you conclude from results, with inference suggestions/applications, if any “Free” slides ◦ Acknowledgments slide (free, not counted) ◦ Closing slide – “Questions or comments?” Logistic Regression of Predicted vs. Observed Trust For subjects who did not trust their putts, the model predicted correctly 69.5% of the time For subjects who did trust their putts, the model predicted correctly 74.5% of the time Pred_Trust 500 No Yes 400 Count 300 200 100 0 No Yes Obs_Trust Cases weighted by Count Example slide 6 Self-Report Ratings & Outcome Putt # Velocity Trajectory (in/sec) (deg) 1 Make Tempo Target? ? (1-10) Let it go? (Trust) Time to BS Start (sec) 56.73 1.487 Y 8 Y Y 1.14 2-9 10 56.60 4.453 Y 7 Y N 1.08 Example slide 7 Acknowledgements This project was made possible by a grant from the Harrah College of Hotel Management, UNLV to Drs. Stevenson & Moore This project was also supported by the Professional Golf Management Program of FSU which permitted use of their facilities for training & testing as well as providing PGM students for subjects Example slide 8 Prescriptions for Success MAXIMUM total slides < 15 !!!! ◦ “less is more” when used wisely, judiciously ◦ “pictures say a 1,000 words” – avoid using text when an appropriate picture can talk Graphs and figures are more powerful than tables; images speak so you don’t have to Use a pointer device to direct audience to what they need to see to comprehend the story ◦ Avoid ‘pointer palsy’; use two hands ◦ Avoid laser light show effects – distracting ◦ Practice your technique to become smooooth… Prescriptions for Success Not every contributor has to present ◦ Give serious thought to who might be the best oral presenters (1-2 shared); avoid “3 Musketeers” effect ◦ Someone should run the A-Vs without interruption (practiced with technology) ◦ 3rd person could field the majority of questions/comments Don’t use notecards or look at slides unless pointing – speak to the audience Prescriptions for Success Don’t read anything – commit to memory Deliver presentation in conversational style, not lecture style Rehearse, rehearse, then rehearse some more! ◦ Present in front of peers for suggestions ◦ Present in front of folks unfamiliar with project ◦ Present with stop watch to time out slides/presentation ◦ Do final rehearsal(s) with faculty mentor for accuracy checks, polishing and finesse tips Prescriptions for Success: Use of Powerpoint Pick an appropriate slide format ◦ Dark or white backgrounds with contrasting lettering are simple, elegant, and nondistracting ◦ Optimize color/background combos ◦ Avoid fancy or ‘cutesy’ designs ◦ Avoid clipart, use real pictures instead Make sure every slide is visible from the back of a large room – scale is important! Prescriptions for Success: Use of Powerpoint Avoid putting too much information on any one slide…avoid ‘dictionary’ or legal disclaimer appearance Prescriptions for Success: Use of Powerpoint Use brief phrases or key words Don’t write out complete sentences ◦ Use bulleting effectively Ditto Ditto, ditto Yada, yada, yada Poster presentations Can be professionally plotted at several places on campus (Allendale, DeVos) ◦ $25 fee, paid at Student Services Access to the plotter Put content into Powerpoint template Use good contrast, colors Use key words, phrases; avoid sentences Use all the space but avoid congestion Examples to view/critique Effect of Training for Trust in Putting Performance of Skilled Golfers: A Randomized Controlled Trial John Stevenson, Paul Stephenson, Matt Hoffman, Travis Jager, and Erika VanEngen College of Health Professions, Cook-DeVos Center for Health Sciences, Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, Michigan Background Group Comparisons Following Training Trust is defined as a psychological performance skill that allows the performer to release conscious control of motor skill execution 1,2, a skill that can enhance the performance of discrete motor tasks such as those found in golf. The performance skill of trust and the construct of flow in sport may share similarities among the dimensions of automaticity, concentration, and composure. However, unlike flow, trust is a moment-to-moment skill, is skill-specific, is ‘all or none’, and can be trained. Use of trust in golf skills performance has obvious value as a performance enhancement intervention. Control Group (23) Training Group (25) ► No significant difference (p=0.521) between groups on outdoor putting performance (5 putts) Trust Education Phase for Both ► Logistic regression results revealed that, in the presence of tempo match and 18 holes on GL system – 9 with KR; 9 no KR 5 hole course on practice green; FSS measures target match, assignment to the training group was a significant predictor of trust (p=0.043) Trust Training for TG only ► When golfers had a high match of their stroke tempo to their preshot routine intention, and hit their intended target, membership in the training group made a significant difference in predicting whether they trusted their putting stroke Drills Practice Log (5x) Recent research3 indicates that when skilled golfers trusted their shot execution: 18 holes on GL system – 9 with KR; 9 no KR 5 hole course on practice green; FSS measures ► gained 20 yards (“on target” distance) ► swing tempo Figure 1. Study design improved to trust ► For both groups, on all trials, a positive report of trust was significantly (p=0.000) Outcome Measures ►golfers rating tempo high were 2.5 times more likely ►Self-report measures of tempo match (1-10), target (Y/N), and trust (Y/N) ►Putt outcome (made or missed) ►36-item Flow State Scale- 2 (pre- and post- 2- For pitch shot performance (30-yd shot): ► reduced distance from hole by 60% training following testing) ►self-report of tempo and target, time to backswing start were significant predictors of trust ► golfers rating tempo high were 3 times more likely to trust related to a positive putting outcome (Figure 3 below) ► For trials with vision permitted, neither group was more likely to report trust in their putting stroke than in trials with vision occluded (p=0.789) Makeand outcome (p=1.00), indicating that ► No relationship was found between KR 1,200 Miss 1,000 Pearson chi-square was used to determine homogeneity of outcome success was not Make dependent on seeing the impact or path of the putt for visual KR groups at baseline for: 1) putting outcome and trust; 2) change in putting outcome and trust between groups; 3) effect of course level on trust; 4) effect of visual KR on trust In 1994, Moore and Stevenson outlined a 3-phase training program (Education, Skills Training, and Simulation) designed to optimize the acquisition and use of trust as a performance skill for discrete, automatized sport skills. 2 The purpose of the education phase is to provide the rationale for trust, explain its characteristics, identify breakdowns in trust, and to gain commitment from the performer to train for trust. The skills training phase aids performers in acquiring trust under a variety of supervised conditions. Finally, the simulation phase puts the performer in a state that is most conducive to trusting performance at that moment, and is done by structuring the routine to take the performer from analysis, to feel, to trust. ► This logistic regression model, with group assignment, tempo match, and target match, correctly predicted the putting outcome 81.1% of the time Figure 2. Indoor putting testing 800 Count 1- For tee shot performance: 600 self-report; and 5) correlation of outcomes and trust. Logistic regression was 400 One-way ANOVA was used on FSS measures, with correction 200 used to predict trust. Characteristic (p-value of 0.006) Training Group Avg yrs experience Avg USGA handicap .724 Control Group P for nine comparisons. 10.75 11.09 Results 5.408 4.565 .077 Table 1. Comparison of subject characteristics 0 Did not trust Trusted Trust Figure 3. Relationship of trust to putting outcome Figure 4. Outdoor putt test The effectiveness of a trust training program designed to enhance trust in the performance of golf skills has not been demonstrated previously. Purpose Conclusions The purposes of this study were to: ► test the effects of a trust training program on skilled golfers’ ability performance Group Comparisons at Baseline to acquire the skill of trust and their putting ►compare measures of the Flow State Scale to trust putting stroke or their putting outcome success ► No significant difference (p=0.318) between groups on baseline outdoor performance (5 putts) self-report putting groups on frequency of trust and no visual knowledge of results (KR) Subjects Participants consisted of 48 skilled golfers from the Professional Golf Management (PGM) Program at Ferris State University, Big Rapids, MI. ► 20-24 yrs of age (45 men, 3 women) ► USGA handicap index between + 2.0 to 8.0 ► Provided informed consent; randomly assigned to ► Trust and flow are not the same performance concept ► Visual KR had no effect on skilled golfers’ ability to self-report whether they trusted ► No significant difference (p=0.578) between ►compare the accuracy of trust self-report under conditions of visual ► Trust training did not have an overall effect on skilled golfers’ ability to trust their their putting stroke self-report ► Indoor putting course level difficulty (Amateur vs. Professional) did not have a significant effect on trust self-report in either the control (p=0.818) or the training group (p=0.037) ► Indoor putting course level difficulty did not have a significant effect on (p=0.53) Training Group Compliance and FSS Measures putting outcomes References 1. Moore and Stevenson. The Sport Psychologist.1991; 5:281-289. 2. Moore and Stevenson. The Sport Psychologist.1994; 8:1-12. 3. Stevenson et al. Annual Review of Golf Coaching. 2007; 1: 47-66. 4. Jackson and Marsh. J of Sport and Exer Psych. 1996; 18:17-35. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the PGM Program, Ferris State University, and University of Nevada Las Vegas for their support of this project. Thanks also to Joel Oostdyk and Adam Miller at GVSU for design and construction of the putting analysis