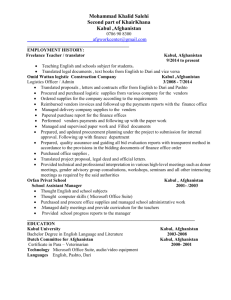

Health Talks Afghanistan WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

advertisement

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Health Talks Afghanistan September 2001 Emergency response “unacceptable” levels of severe malnutrition, given the existence of a general food distribution. The centre saw a 3% death rate in July and August. One factor is the high rates of diarrhoea prompted by poor water and sanitation services which have been the subject of a massive effort in construction over recent months. But the picture is complicated by the reluctance of mothers to take children to the therapeutic feeding centres, possibly because they cannot be away from the rest of their family all day. MSF is about to duplicate both the supplementary and the therapeutic feeding centre to cope with the numbers. Agencies race winter to protect IDPs With winter just six weeks away, and numbers of displaced from rural areas continuing to grow particularly in the Northern region of Afghanistan, international and national organisations are racing against time to get protective measures in place. In Herat the camps set up for the displaced continue to grow by around 8,000 people a month and many are still housed in rough shelters giving little protection. The International Organisation of Migration which administers the largest camp in Herat estimates at least 6,000 new shelters are needed to house families which have already arrived and another 6,000 in preparation for those who may come before winter closes the roads in mid November. A further 4,000 shelters in Maslakh camp need repairs. In the Northern region, many small ad hoc camps are scattered across a wide area, making it even more difficult to provide assistance. Last winter, at least 150 people died from cold and exposure in Maslakh camp in a week which saw temperatures unusually plummet to -25ºC. WHO is particularly concerned that cold, overcrowding, poor nutrition and the resulting lowered resistance to conditions such as respiratory tract infections could have a tragic consequences particularly among children, many of whom are under nourished. Like others the agency is appealing for funds to help maintain essential drug supplies, improve staff capacity and support emergency needs in water, sanitation and fuel supply. “We need to be able to support the IDP health clinics in treating patients quickly and well this winter, and be ready to help with fuel supplies and other materials to protect against the cold,” says WHO officer in charge in Herat, Dr Mohibullah Wahdati. Distribution in remote Ghor The International Committee of the Red Cross has begun a massive distribution of aid in Ghor province where fighting and drought is severely affecting the population. Over the next month, some 11,500 metric tonnes of food, seeds, blankets, kitchen and water equipment and other non-food items are being trucked into the drought and conflictstricken area in an effort to help families avoid displacement from areas that remain secure. Médecins sans Frontières has also this month started a programme to feed children in several areas of Badghis province identified as most vulnerable to try and help people stay in their own homes. But medical co-ordinator Lindel Cherry says it is crucial that other agencies also act in these areas if people are to stay. “We can do our part but if they don’t have a water source, they are not going to stay. Promoting safe delivery wherever Some 100 traditional birth assistants are being trained in the principles of clean and safe delivery, danger signs and how and when to refer in the Herat IDP camps this month. The work is a combined effort between WHO, UNICEF, WFP which is providing ‘food for training’ and implementing NGOs such as Médecins du Monde and Ibnsina. The group also hopes to train a further 100 in camps in the Northern region of Mazar before winter. WHO maternal and child health officer Dr Annie Begum who carries out the training with local physician trainers says training TBAs is valuable Malnutrition at worrying levels Two supplementary feeding centres in Maslakh camp in Herat are providing extra rations for more than 2,000 children every day, and Médecins sans Frontières, which runs one of the centres plus therapeutic feeding centres in the camp and in the city’s hospital, reports 1 September 2001 This document was researched and written by Hilary Bower, information officer for WHO Emergency and Humanitarian Action Department, Geneva, The content does not necessarily reflect official WHO views or policies. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION even if they are again displaced or return to their home. “They take the knowledge with them and in some cases we will be simply refreshing those who were trained by the international community many years ago.” The vast majority of Afghan women give birth with only the assistance of their family members and the country has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. (see page 7) district earlier this month. While IOM provided transport, Oxfam is providing seeds and other basic help in the targeted villages. For its part, WHO is appealing for $6.5 million dollars to reactivate health services and facilities in 27 districts to help prevent displacement and encourage those in camps to return to their villages. The project involves activities from building capacity at district level to manage and support health services through to supplying and reequipping facilities and training health staff. Linking camp clinics to families WHO and NGO teams running the five clinics in Maslakh camp are to set up defined catchment areas for each clinic this month to reduce overcrowding and duplicative use of the clinics, improve the links between clinics and the families they serve and the ability of health educators to reach every family. From the new grid system being applied in the camp, WHO and the health teams will identify coverage areas for each clinic, and will supply families with a numbered family health book, detailing the names and ages of the family head and each family member. This book will be used to track a family’s health and well being and provide epidemiological data. At present, fewer than 20 health educators work in Maslakh camp, despite large problems with hygiene, nutrition and missed illness. With the catchment system, health educators will be responsible for a certain fixed number of families who they will visit regularly. In a linked initiative Médecins du Monde is dramatically expanding the number of health educators in the camp, adding an extra 60 who will be based in 10 ‘container’ health posts in the areas of the camp covered by the NGO. The idea, says MDM head of mission Thomas Durieux, is for the health workers to provide health education on a shelter to shelter basis, to encourage the formation of communities around the containers, and to provide ‘first aid’ to take some of the load off the clinics while improving the attendance of the seriously ill. IDP coordinator appointed WHO has recruited a dedicated international IDP co-ordinator and intends to employ two further national IDP focal points in the North and the West to reinforce its assistance to internally displaced populations and the organisations working with them, and extend its public health programming. Dr Yusuf Hersi intends to survey all IDP settlements, both organised and ad hoc, to get comprehensive picture of the public health situation. He is also keen to develop a system of needs reporting and supply which will allow to NGO and MoPH health facilities working with IDPs to receive appropriate drugs directly in a more coordinated fashion. Communicable disease Donations target tuberculosis Donations of $850,000 from Italy and $350,000 from Norway have brought back into sight the possibility of tackling the country-wide TB control and treatment in Afghanistan. More than 16,000 people die of TB every year in Afghanistan and the situation has been worsening as more and more people find themselves displaced, poorly nourished and crowded into poorly ventilated tents and houses. Herat Hospital estimates it has seen its tuberculosis patients more than double in the past two years. Other than in the main cities, TB clinics are few and far between, drug supplies are erratic and expensive for patients, and health worker knowledge of how to effectively cure TB is poor. Indeed poor and irregular pay makes for low motivation among staff which is especially damaging for a disease which requires a high level of supervision. Ironically, though massive displacement is exacerbating spread of tuberculosis in Afghanistan, the same movement of population, plus the timely donation of monies, may also provide crucial opportunity for cure since thousands are pouring into urban centres from Returnees will need major support The International Organisation for Migration says more than 20,000 people in Herat have registered to return to the original homes if conditions are right, including a large number of ethnic minority people. “In Faryab, for example, we believe it would be possible to get a significant number of people back to the place of origin by dealing with the provision of drinking water and food,” says a spokesperson. Two ‘pilot’ returns have already taken place. Thirty one families in one group and 91 in a second returned to their villages in Gormach 2 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION rural areas where there has been no access to TB programmes for years. “People often say there’s no point in treating people in camps because of the instability, but for many of these people there is no place to be treated where they come from,” says WHO representative to Afghanistan, Dr Said Salah Youssouf. In other countries of complex emergency, such as Somalia, TB programmes bring patients to specific camps for the length of their treatment to allow good supervision and supply of correct drugs. In some ways, displacement may have inadvertently started this process in Afghanistan. The Italian and Norwegian donations will be channelled through WHO to a wide partnership of international and national players (see below) and allow the launch of intensive efforts to cure existing sufferers. This includes providing supplies to treat some 13,000 patients a year – more than three times the current rate – re-establishing laboratory diagnosis facilities, and training staff to work with the gold standard DOTS or directly observed treatment short course strategy. It is hoped that the new money will also allow some staff incentives to be paid. ensure logistic and administrative support to the demonstration sites, and for expert NGOs to help expand activities into areas without treatment facilities. Donations from the Italian and Norwegian governments totalling over $1.2 million will make moves to follow these recommendations possible. Drugs plus food raise cure rate In Kabul, the German Medical Service’s 30-yearold tuberculosis treatment centre has a cure rate of almost 85%, with less than 10% defaulting on the six-month long treatment. “Let me tell you the miracle,” says programme manager Reto Steiner. “We are able give people an incentive. We give them food – wheat, rice, vegetables and oil – and it has the dual benefit of reducing defaulters and making sure the patients eat better.” In Kabul GMS treats some 800 new cases a year. A second specialist NGO, Medair, supports Ministry of Public Health TB clinics and treats more than 1300. A Medair survey last year estimated that some 10,000 people in Kabul contract TB every year. Very few NGOs are presently involved in TB care outside of Kabul. However, one model site is NGO Lepco’s centre at Chak e Wardak, some 2.5 hours drive on rough roads from Kabul. Here Dr Mahd Arif tends patients and a profusion of flower gardens with equal care and DOTS is implemented strictly with high cure and low default rates. Dr Paulo Mantellini is WHO’s new Stop TB coordinator for Afghanistan. He can be contacted at the WHO Afghanistan office, ph:+92 51 2211224 or via any WHO in-country field offices. Demonstrate DOTS, says conference DOTS (directly observed treatment short course) ‘demonstration’ sites should be developed in each region to gradually introduce strictly controlled therapy for TB nationwide, according to participants at the first National Tuberculosis Coordination Meeting held in Kabul in August. Conference participants, which included over 40 ministry and NGO representatives, were adamant that DOTS should be the main form of treatment, but equally insistent that it should only be introduced in a step-wise fashion to avoid further development of drug-resistant TB. DOTS should only be expanded when these demonstration sites, which will receive free drugs and food support, are producing high cure rates said delegates, who advised against too rapid expansion. The use of the most important weapon against TB, rifampacin, especially should be limited to DOTS sites with good supervision. Where DOTS cannot be guaranteed conference participants said patients must only be given regimens which do not include rifampacin. Delegates also called for recruitment and training of TB coordinators and deputies for each region who would train, supervise and Outbreak in North but Kabul cases down A serious cholera outbreak is continuing in Afghanistan, particularly hitting regions where there are major IDP populations. But in Kabul, preparedness activities seem to be paying off. So far this year there have been some 5000 cases and 100 deaths from cholera outbreaks, many of which have been in the Northern and Western region where large numbers of IDPs have gathered. On top of crowding and poor hygiene conditions, drying up of shallow wells has forced large populations back onto river water which is easily contaminated. NGOs such as Médecins sans Frontières, the Danish Afghan Committee, the Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees and local NGO Coordination of Humanitarian Activity, have set up cholera camps in several areas to provide life-saving oral rehydration therapy. They also continue to carry out chlorination of wells and health education while WHO provides cholera kits and technical guidance when needed. In Kabul, however, several years of preparedness and prevention work appears to 3 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION have been able to limited cases in the capital, of which it was once said that health workers could predict everything about the annual cholera epidemic except the names of the people who would die. While UNICEF has provided chlorine and WFP food for work for well chlorination, WHO and NGO partners have intensively trained community and health workers in prevention techniques and hygiene education, as well as in quick identification of cases – all of which seems to have paid off this year with no outbreaks reported so far compared to 6,400 cases in 1999. Social stigma attached to leishmaniasis is high particularly for women who may be thrown out of their home, and both sexes are frequently barred from sharing food and ostracised. A guide to treating cutaneous leishmaniasis in Afghanistan and Pakistan has been developed by and is available from HealthNet International and WHO. Haemorrhagic fever strikes again WHO is investigating three reported deaths from haemorrhagic fever in the Western region of Afghanistan. Diagnosis of Crimean Congo haemorraghic fever was made in Iran in one case, who travelled there for treatment. Another is thought to have travelled by car to Pakistan, while the third died in Farah province. Last summer an outbreak of CCHF in the Herat region took 15 lives before being brought under control. A WHO headquarters outbreak team trained healthcare staff, who are particularly at risk since the highly infectious disease is transmitted through often minimal exposure to contaminated blood. The WHO office in Herat maintains a store of Ribavirin which is crucial to protecting contacts. The Organisation urges anyone who encounters deaths involving bleeding to contact a WHO sub-office or the support office in Islamabad immediately. Leishmaniasis epidemic spreads The extended epidemic of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul city has now reached 50,000 new cases a year. And there are fears that a new outbreak may erupt as internally displaced people move into the newlyconstructed Sakhi camp in Mazar-e-Sharif. The camp is sited in an area well populated by giant gerbils, the rodent carrier of the animalborne form of leishmaniasis, says Dr Kamal Mustafa, WHO’s officer following the disease. “We have sent bed nets especially to target women who suffer the greatest social stigma from leishmaniasis, and we have prepositioned 3000 vials of pentostam, the treatment drug, in Mazar in case of outbreak,” he says. The epidemic in Kabul is mainly due to population displacement and environmental damage from the war which has provided the ideal environment for the sandfly which is the vector for the human-to-human form prevalent in the capital. But the disease has also appeared for the first time this year in Faizabad and unusual numbers of cases are turning up in the northern and southern regions, all most likely as a result of displacement, says Dr Kamal. Treatment is the first line of control because if the sand-fly cannot feed on the lesion, it cannot transmit. In 2000, collaboration between HealthNet International, Japanese NGO TODAI, IMPD and WHO, enabled the treatment of almost 36,000 cases Kabul and 17,000 cases in other regions. One element was WHO’s discovery of a new source of reliable drugs in India which cut the cost of a 100cc from $100 to $10. The organisations also ran training in diagnosis and treatment for male and female doctors, nurses and laboratory technicians in five regions to encourage the prompt therapy that can greatly limit the effect of the disease. Left alone leishmaniasis will eventually cure itself, but often only after the victim has suffered multiple ulcers which are not only susceptible to other infections, but leave disfiguring scars. Drought brings back Gulran disease An unusual and rapidly fatal liver disease, last seen in the drought of the 1970s, has reemerged in the Gulran district west of Herat. Named after the district, Gulran disease is linked to a common weed called charmac and causes rapid liver damage, anorexia and fatigue. In advanced stages, patients develop hugely extended bellies, wasting and bruising, which can be confused with kwashiorkor. So far in this outbreak there have been 400 reported cases and over 100 deaths since mid1999. In 1975, after two years of severe drought, almost 25% of the region’s then 7200-strong population developed liver problems and over 1600 cases were reported. The condition appears to be linked to drought conditions and WHO is currently conducting studies to find out what is the most important risk factor. “Some of our theories are that consuming charmac seeds mixed with wheat or drinking milk from goats which graze on charmac may be the cause of the disease,” says WHO communicable disease officer, Dr Rana Graber. Salty well water and poor nutrition appear to exacerbates the effects and lack of knowledge among health professionals means response is often late or incorrect, all leading to a very high death rate from the condition. Improving 4 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION nutrition, separating the weed from diet, and good hospital care can reverse the illness, but action has to be taken quickly once the toxicity becomes evident. A WHO plant biologist will arrive this month to investigate the phenomenon. A collaboration between WHO and specialist NGO HealthNet International, the project has doubled its original stock of 200,000 nets through cost recovery, while also distributing more than 260,000 nets over the past two years. The programme focuses on pregnant women and children under five who are the most vulnerable to bad outcomes with malaria. Areas where more then 30% of the malaria is caused by the more dangerous falciparum parasite are also targeted. Nets are sold for between $1.50 and $3 each. Other key components of the project are training in re-impregnation methods, community awareness-raising, health education for prevention and health worker training in appropriate treatment and prompt diagnosis. HealthNet International also runs a similar programme in the refugee camps of Peshawar where programme manager Dr Abdul Rab reports there has been an over 50% reduction in falciparum malaria. Funds for malaria currently come from the European Union via HealthNet and WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean regional office which also supplies about a third of the countries needs for choloroquine and sulphadoxinepyrimethamine or Fansidar. NGOs make up the vast majority of the remainder. Roll Back Malaria Poor immunity puts displaced at risk People displaced from the Central Highlands into the endemic lowlands are now among the most vulnerable to malaria. “These people are the real victims of malaria. They are the ones who are dying because they have very little immunity,” says WHO Roll Back Malaria officer Dr Kamal Mustafa, who is currently organising a series of four situation analyses to underpin the implementation of the Roll Back Malaria programme in Afghanistan. The first survey took place in August in the opposition territory of Badakhshan and surveyors are now visiting the remainder of the North East (Kunduz, Baghlan and Taloqan) which is the most highly endemic area and due to the frontline passing directly through it, the most difficult to access. They will also survey the Eastern region which is highly endemic and an area to which refugees are likely to start returning and Kandahar/Helmand in the South which has a low prevalence of malaria but is the most prone to epidemics of malaria, due to the presence of large numbers of displaced from the central highlands and its position on the transit route through to Iran. The situation analyses are the first step towards creating strategies for Afghanistan under the Roll Back Malaria programme which aims to control the disease through access to prompt diagnosis, appropriate treatment, raised awareness and preventative measures such bed nets and environmental control. Collaboration across sectors and with all possible players is also a fundamental tenet of the programme. So far 38 of the 54 NGOs working in health have agreed to participate in the programme. Seed funding of $25,000 has been provided by WHO and $10,000 by cosponsor, UNICEF. But far more will be needed if the strategies that result are to reach the 13 million people at risk. Mental Health Spotlight on psychological health WHO is about to begin an Afghanistan-wide assessment of the mental health situation and activities in the field. An Afghan doctor trained in mental health and psychology in India, Dr Said Azimi, hopes to complete the field work before winter and use the results as the foundation for a national level workshop on mental health for potential partners including the Ministry of Public and NGOs. Dr Azimi also carried out a three-week awareness raising course for male physicians in Kabul this year covering both pathological and psychological disease. WHO hopes to repeat the training for female physicians if funds can be found to support a female trainer from overseas since no Afghan female doctors have adequate skills in the area. Currently there is little mental health training in the Afghan medical curriculum nor, outside of Kabul any psychiatric hospitals. Some organisations do have mental health activities, such UNICEF’s grief and trauma counselling courses in Kabul, and it’s hoped the assessment will both support the development of knowledge and awareness nationally and enable WHO has translated management guidelines, teaching manuals and health information materials into both Dari and Pashto. Please contact Dr Kamal Mustafa for copies. Bednets prove self funding Afghanistan’s largest bed net programme is proving to be almost self funding. 5 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION organisations and funders to identify appropriate activities. Targeting micronutrients in Kabul Micronutrient deficiency is prevalent in many parts of Afghanistan particularly among women, girls and children. In Kabul, WFP and WHO are working together to ensure that bread consumed by some 500,000 people from the food agency’s assisted bakeries projects is boosted with essential micronutrients. While WFP co-ordinates and supplies the bakeries, WHO has added funds for the micronutrients and trained WFP staff in awareness of the problems and solutions. Micronutrient deficiency is a major cause of birth defects as well as poor health. WHO has also trained 22 health professionals from across Afghanistan as trainers in community nutrition focusing on how to integrate the promotion of nutrition into health care services, assess community needs, develop growth monitoring activities and nutritional counselling, and promote breastfeeding and proper weaning. Some 200 health staff have now been trained in community nutrition. Nutrition Vulnerable pinpointed in new surveys Nutritional surveys are taking place in four regions of Afghanistan in an effort to quantify the risk of increasing malnutrition in the run-up to winter. Supported by the funds from the US Government’s Disaster Assistance Response team UNICEF, Médecins sans Frontières, Action Contra la Faim, and Save the Children Fund (US) are carrying surveys in the North East, North, West and Southern districts. The aim is to get nutritional indicators in three key communities: IDPs, populations living in areas worst affected by the drought, and those living in less affected areas. Levels of acute malnutrition have, until this year, rarely been reported above 7-8%, partly because even when coping mechanisms are extremely stretched, Afghan families prioritise children. But chronic malnutrition appears to be high, affecting growth rates and vulnerability to infection. UNICEF is also working to try and streamline the collection of nutritional data so as to make it comparable across the country. However, one problem to be overcome is how to maintain the comparability with figures collected in the past in a particular region if the approach is changed. Child Health Immunisation needs outreach boost WHO and UNICEF hope to introduce the concept of ‘sustainable outreach’ immunisation services later this year to try and boost persistently low level of childhood vaccination. Although there has been a tenfold increase in the number of fixed immunisation points – from 50 in 1992 to 556 in 2001 – and over 1200 vaccinators incentivised by UNICEF are sited in 266 of the country’s 332 districts, the number of children protected by essential vaccines still struggles to make it over 40%. Two key problems persist according to according to UNICEF senior programme officer, Dr Solofo Ramaroson: the ability to reach deep into the remote and difficult terrain and to correctly supervise and monitor immunization throughout the country. Sustainable outreach takes the principles of the polio national immunisation days with their high level of social mobilisation and community participation and applies them to routine vaccination using teams which visit remote and under-served areas two or three times a year, actively seeking out children, says WHO’s Dr Mojtaba Haghgou. Poor economy hits children Over 15% of severely malnourished children admitted to the therapeutic feeding centre in Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital in Kabul in July died despite efforts to save them, says clinic supporters Action Contra La Faim. Most of the children come from Kabul city or nearby districts, says clinic co-ordinator Dr Asef. “But they often come very late and in very bad condition because they usually go to a private doctor first.” Over 120 children were admitted in July 2001, compared to 80 last July. “The most important causes of malnutrition are economic problems and low education level, “ says Dr Asef. “Families are eating very poor quality food. They can only afford low quality rice and tea – they can’t buy milk or meal. Then if the children get diarrhoea or respiratory infection, they lose weight very quickly.” The clinic’s 35 beds are overflowing with wizened marasmic children, while up in the nursery, senior nurse Nooria says the average weight of newborns is between 2 and 2.5kgs. “We expect it when mothers are so small and malnourished,” she says. Afghanistan gets first GAVI grant Afghanistan has just been awarded its first funding from the Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunisation (GAVI). The target is to vaccinate 50,000 more children with the DPT 3 (Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus) vaccine by 6 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION adding 25 new fixed centres in remote and under-served regions, working right down to household level to ensure full take-up of vaccines and training health workers and managers in follow-up of children. The fund will, unusually, be managed by WHO and UNICEF rather than going directly to the country government. skills in emergency obstetric care among female health workers in clinics and hospitals in Afghanistan. While WHO is targeting its initial round of the Safe Motherhood Initiative on Kabul, Herat, and districts in the south eastern region and the north eastern region, working through health NGOs such as the Swedish Committee for Afghanistan, Ibnsina and local health NGO AHDS, UNICEF is focusing on the south eastern provinces of Laghman and Lowgar, plus Farah province in the West and Balkh in the North East. The children’s agency hopes next month to start teaching a new curriculum developed with WHO with the help of an WHO consultant in the field. “We want to work on the supply side – there’s no point in creating demand if when women are referred there’s no good services. Nurses and female physicians in clinics have to know what to do in obstetric emergencies, says UNICEF’s Dr Solofo Ramasoron. Afghanistan has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the world – some 16,000 women (1700 per 100,000 live births) die every year of causes related to pregnancy. Among the causes are: poor availability of reproductive health care and motivated, skilled health workers, lack of access to female doctors, very few midwives, poor referral possibilities, lack of supervision, low education and literacy levels among women, and lack of resources – all added to the problems of a remote mountainous country and ongoing conflict. To tackle these problems, the Safe Motherhood Initiative aims to introduce the skills needed to provide essential obstetric care at different levels of the health service and train health staff in components ranging from antenatal care through to hospital level emergency obstetric response. However, says WHO maternal and child health officer, Dr Annie Begum, important though it is to improve secondary care, it is essential to continue training traditional birth attendants since 90% of Afghan women give birth at home. “People say that TBAs cannot manage women who suffer obstetric complications, but in rural areas where there is nothing, women rely on them so we have to train them in how to conduct a clean and safe delivery, how to recognise the danger signs, when and where to refer to and how to provide first aid before referring.” Dr Begum says the targeted districts are those where there is the potential to form referral links from the TBAs through a health clinic and to a district hospital. Since 2000, WHO has trained 50 female physicians in essential obstetric care, 36 TBA Polio eradication Strong national teams will do NIDs At the time of writing WHO and UNICEF hope to see the first round of the 2001 national immunisation days (NIDs) go ahead as planned on 23-25 September, despite the temporary evacuation of international UN staff from field offices in Afghanistan earlier this month. Expanded programme for immunisation team leader Dr Naveed Ahmed Sadozai says that if international staff cannot be present, the strong national staff team is fully capable of implementing the NIDs. The NIDs this year are synchronized with those in neighboring Pakistan and are the most recent efforts in a campaign that is beating back the polio virus despite enormous odds. So far in 2001, there have been only 9 confirmed cases compared to 27 cases in 2000, and 63 in 1999. Surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis, the marker used to spot polio, has also improved dramatically as has investigation of each individual case, largely due to a network of 237 sentinel sites and focal points across the country. “We believe we now get to know about almost every case of AFP,” says surveillance officer Dr Mojtaba Haghgou. “Many patients go first to a mullah or community leader, so we have trained them to report cases also.” Surveillance data show four remaining hotspots for wild polio transmission in Afghanistan. Two border Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province and Balochistan in the south. The other two are Herat in the west and Kunduz province in the north east. Co-ordination and synchronisation of activities in border areas will be crucial to ensure eradication, says Dr Naveed. Routine vaccination has also benefited from the investment of the polio campaign, increasing from 7% before NIDs started to 36% in 2000 as a result of improvements in cold chain and staffing dedicated to vaccination. Maternal Health Targeting essential obstetric care In the fight against atrocious rates of maternal mortality, both WHO and UNICEF have this year shifted their focus to concentrate on developing 7 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION “They are very motivated, they can teach very easily and it gives hope to the patients that there is a life after disability. It’s not easy to lose a part of the body but we work to help them find a way.” Services and staff are mirrored exactly for men and for women, and the centre recently added a job centre, vocational training and a micro-credit operation to its activities. ICRC, which opened its sixth centre last month in Faizabad, has helped over 45,000 people since 1988, almost half at the Kabul centre. Sadly there is little sign that their activities will be any less needed in the near future. trainers and 580 TBAs who now work in 400 villages across five regions. WHO has translated various Safe Motherhood texts adapted by the maternal health taskforce into Dari. Please contact Dr Begum at WHO for copies. Tracking the gaps that lead to death WHO and the Ministry of Public Health hope to pilot a maternal death reporting system in seven hospitals in Afghanistan. The aim is to track causes of maternal death and identify the gaps in service that have the most fatal effect. Community effort for safe delivery kits Only 12% of women deliver in the care of a person trained to help her. This leaves the vast majority of women giving birth aided only by family members. To help them, WHO and UNICEF plan to train traditional birth attendants and women in communities on how to assemble a disposable safe delivery kit using locally available materials and the importance of utilising all the elements. “We hope increasing availability of the kit will help reduce neonatal tetanus. And making the kits could also become income generating for some families,” says WHO’s Dr Annie Begum. Water and sanitation Turning on the tap in Faizabad For the first time in their lives, all the residents of Faizabad city have access this year to piped water, thanks to UN agency collaboration. The $550,000 project in the capital of the opposition territory not only involved extending a completely new water distribution network into the new city, but also two large water reservoirs in the hills above the city, and even a flood protection system “to protect lives, and our water project,” says WHO’s water and sanitation engineer, Dr Riyad Musa Ahmad. Together with an earlier project which brought water to the old town, the network now benefits all the city’s 50,000 inhabitants. While WHO implemented the project and employed the engineers who designed and supervised the construction of the network, UNICEF brought the piping, and the World Food Programme provided food for work to the labourers. Hygiene education is also a key part of the project, says Dr Musa, and trained health educators have been working within the communities to promote healthy and hygienic practices with water. “WHO usually focuses on quality of water but when there is very little quantity this affects sanitation which inevitably affects water quality. This is why we, and the other agencies, believe this project is so important,” says Dr Musa. Rehabilitation Disease is also war damage One in five people given back their mobility at ICRC’s orthopaedic centre in Kabul have been disabled not by rockets or landmines, but by the lack of access to good medical care. The centre sees about 200 new patients a month, 80 per cent of which suffer from minerelated amputations. But around 20% of them are disabled by other causes such as polio and cerebral palsy. “In a way they are war victims too,“ says centre manager Mr Najmuddin. “They are disabled because they didn’t get the vaccine or the health services they needed or because there were difficulties with their birth. We have many many children with polio contracted before the polio campaigns began.” Whatever the cause, the centre – the largest of its kind in the world – not only makes and fits prosthesis and supplies ICRC’s five other centres in Afghanistan, but also ensures through physiotherapy and careful fitting and practice that the patient is “100% able to use it.” They know what they are teaching - over 75% of the 150 staff have been through the process themselves. “In the past people thought disabled people couldn’t do anything, but we have many disabled people working very hard here, ” says Najmuddin who lost both legs at 19 in a mine blast and has managed the centre for 13 years. Japanese support Northern IDPs People displaced by drought into some of the many camps scattered across the Mazar-eSharif and Kunduz provinces will benefit from a $160,000 donation from the Japanese Government which is to be used to construct latrines and make water quality improvements. The funds are being channelled through WHO’s water and sanitation programme for Afghanistan which is now targeting the Northern region since 8 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION many other agencies involved in the water sector technical group have responded to the needs of the IDP camps of the Western Region. The money will be used to improve quality of water and sanitation in the camps and surrounding areas, says WHO engineer Dr Riyad Musa Ahmad, by providing micro sand filters. Around 20 district hospitals in the area will be fitted with the technology which has been especially adapted for conditions in Afghanistan. Filters, which produce good clean water at relatively low cost and with little maintenance, will also be supplied for communities and families in the IDP camps. backed the project with $230,000 with a further $100,000 donated by the Italian Government. Weekly watch spots outbreaks better MSF Holland has set up a weekly ‘alarm call’ system for six epidemic-prone diseases that has significantly improved response to communicable disease in Kandahar. The project, which started in September 2000, involves 18 sentinel sites which collect and analyse data on cases of malaria, meningitis, measles, typhoid, watery and bloody diarrhoea on a weekly basis. “Last summer we felt we were always running after diseases. With the alarm call system we have been able to manage diseases that could potentially have got out of control, such as the meningitis outbreak in June this year, in a much more proactive and coordinated way,” says MSF-H medical coordinator Beverley Colin. A key element in the programme, which was adapted from a ‘weekly watch’ piloted by WHO in Kabul last year, is the teaching health workers and community leaders to recognise the early signs of an outbreak, and to act on the information. Too often, the beginnings of an outbreak are only picked up weeks after, either because available data is not analysed locally or because there is no data collection. “This makes a big difference to the speed of response,“ says Ms Colin. For example, health workers in Badghis recently started seeing a 50% increase in fever cases and were immediately alert to the possibility of malaria outbreak which in turn allowed the emergency taskforce to plan a response. MSF has integrated the alarm call system into the new nation-wide health information system by using the same case definitions and incorporating the data into monthly reporting. WHO is seeking funds to build on and spread on the experience of these two models particularly into areas where accumulations of IDPs are creating ideal conditions for outbreaks. “The key is to have people watching for early signs of a problem, knowing who to call and seeing a response.” says Dr Rana Graber, WHO’s officer for health information. Health information Disease data starts to flow A country-wide health information system launched in May should soon start producing long-needed data on disease burden. Since January this year over 900 people someone from almost every health facility in Afghanistan – have been trained in both the use and principles of health information by the Health Information System Taskforce, a team which involves the Ministry of Public Health, WHO, UNICEF and major NGOs such as Swedish Committee For Afghanistan, Ibnsina, Médecins sans Frontières and Aide Medicale International. The system has been designed by the taskforce over the past two years and will provide detailed information on 36 conditions plus infant and maternal deaths and causes, and referrals in a country for which accurate statistics are like gold dust. The arduously-developed standard case definitions should also allow comparisons to be made across the country as well as helping refresh and focus diagnostic skills. Though it will take some time to gain momentum, when all health facilities are reporting regularly, more than 10,000 forms will flow initially into WHO offices and eventually, it is hoped, into national health information units. Funds allowing, WHO plans to base a computer expert in Kabul next year to train Ministry of Public Health staff in input and analysis of data, as well as basic computer skills. Collecting health information is crucial to tracking trends, identifying priorities and monitoring impact over time. While it needs to be analysed centrally training has focused on enabling each health facility to use their own data for decision-making before sending the data to a higher level, says Dr Rana Graber, WHO health information officer. WHO has Primary health care Modelling ‘sustainable’ health care WHO wants to launch model ‘sustainable’ primary health care centres in 22 districts this year, in collaboration with the Ministry of Public Health and various NGOs. The concept rests on developing community participation to manage and financially support re-invigorated curative and preventive services. 9 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION “If assistance stops tomorrow, what will happen?” asks Dr Abdi Momin Ahmed, WHO officer for primary health care. “The vast majority of functioning health clinics in Afghanistan only exist because of external funds. We want to sensitise the community to support their health workers, to assume responsibility for their own health care systems so that if assistance leaves, the system does not collapse.” The programme has several key elements. One is an intensive programme of orientation and skill building in community management and financing of health services (see below). Health workers also need to be updated in essential disciplines, says Dr Momin, and concrete practicalities put in place, including providing basic equipment and essential drugs to some 75 basic health centres, and carrying out some physical rehabilitation on at least 16 units. So far five district health teams have been trained in the concepts of sustainable health care and introductory work has been done with regional health authorities to gain their support. However substantial funding is needed to move into the implementation phase both the larger towns in Afghanistan and over the border in Pakistan can tip the balance between staying and going.” Although the number of districts providing essential primary care has risen from 12% in 1990 to 48% in the year 2000, the situation is still dire in many parts of the country since geography, insecurity, quality of service and availability of supplies prevent many from accessing the care they need. Cost recovery on drugs helps usage Cost recovery projects run by NGOs have met with surprising success. HealthNet International’s primary care project in Eastern Afghanistan is achieving over 70% cost recovery on drugs, for example. Focused on the Shinwar district, HNI has fostered a complete health care system from community through primary care to the district referral hospital and underpins this system with supplies, equipment, incentives and managerial support. The Swedish Committee for Afghanistan, which supports over 160 health facilities in remote regions of Afghanistan also uses cost recovery, charging patients 40% of the market price for drugs and 1000 Afghanis (US$0.01) for consultation. Male and a female health committees identify the roughly 10% of patients too poor to pay even this meagre amount. “If we give drugs for free, patients don’t trust the drug and throw it away. We have also been working for a long time to teach people in our communities about rational drug use and now they are beginning to believe us when we say a drug is not needed,” says Dr Shafi Saadat, SCA’s head of the health programme. Goal is to avert displacement WHO is carrying out a survey in four provinces in September and October to get information on primary health care support and the level of operation of facilities with a view to targeting investment in clinics in communities vulnerable to displacement. The first survey will take place in Nangarhar and Laghman, says primary health care officer Dr Abdi Momin Ahmad, because of their easy accessibility and the presence of large numbers of farmers previously involved in opium poppy production. Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif will be covered next because of the drought situation there. In the Western District, the survey will be the first step in a displacement prevention package, designed to run alongside other similar programmes involving food and seed distribution and well improvement. Under this ‘survival’ package, WHO is appealing for some $3.5 million to get 27 basic health centres back to an appropriate operation level and supply and supervise them for nine months. “Though a functioning health centre alone will not keep people in a village or be the main reason why they return, it is an essential part of the jigsaw of social and economic support needed to avert displacement and encourage return,” says Dr Said Salah Youssouf, WHO representative to Afghanistan. “If a family member is sick, the pull of health services in Evaluation of basic needs project WHO is to evaluate its long-standing basic development needs programme this year. The programme involves giving loans for projects ranging from health education to literacy classes and income generation activities with the aim of improving health through improving basic living conditions. It is now present in 14 villages in four regions. A 15th village in the central region has just carried out the baseline survey that underpins the initiative and which aims to identify action areas across all sectors. The aim is for the community to use the baseline survey which they carry out themselves, to develop an overall development plan and to identify priority activities which will improve their quality of life and health. From this, a committee develops small projects for funding by UN and other organisations, either directly through money or via approaches such as food for work. 10 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION One village has targeted literacy programmes for women, for example, while others prioritise income generation, or health-related issues such as improving vaccination rates, educating traditional birth attendants or clearing mosquito breeding grounds. health and higher education, and the Liverpool School of Public Health, has a mixed intake of 20 males and females as is allowed in the Northern Alliance sector. It covers management of health services at district level and practice in major clinical areas such as mother and child health, epidemic diseases, vaccination and nutrition. Two similar courses were held for men last year in Kabul, and for women in 1997 and 1998 in Kabul and Herat respectively. Because of the scarcity of Afghan female lecturers, female courses are more difficult to organise, says WHO education and training officer Ms Alexandra Taha. But it can be done by supplementing Afghan teachers with international NGO and WHO lecturers. Ms Taha is also hoping to hold follow-up courses for the male directors to promote an environment in which female participants might be more able to put into practice what they have learnt. Indeed, a step in this direction was the first oneweek course for provincial directors of health who are usually non-technical religious leaders supported by a medically trained deputy director. The programme ran through essential primary care areas including communicable disease control, water and sanitation, essential drugs, immunisation and mother and child health. But it also focused on key elements of service such as teamwork and community organisation, and included a visit to Healthnet’s primary health care community participation pilot project which is achieving 70% recovery of costs on drugs. “This astonished the directors who hadn’t believed the community would be willing to pay for drugs and better services,“ says Ms Taha. Diagnostics Tackling training and supplies Sixteen laboratory technicians from across Afghanistan gathered in Kabul in early September for a two week refresher course in laboratory techniques and diagnosis. The course is part of a series of training sessions over the past two years which WHO has carried out both centrally and at regional and district level to upgrade laboratory and diagnostic capacity. WHO provides the majority of available laboratory supplies since the Ministry of Public Health does not direct any resources to the area and NGO support is general restricted to small clinic laboratories. WHO hopes to improve the supplies to laboratories next year by employing a national officer who will travel through out the country to help strengthen and monitor the supply chain, as well as provide technical support to the regional and provincial laboratories. Some facilities have, for example, been found to have good stockpiles of some chemicals which cannot be used because they are missing a single element. “The aim is to have fully functioning laboratory in each region working together with the national level,” says Dr Said Salah Youssouf, WHO representative to Afghanistan. WHO is also re-equipping radiology units and retraining radiology technicians in good practice and in maintenance. Three new x-ray machines have been installed in 2001 – two in Kabul and one in Faizabad – and three more on order are destined for provincial hospitals. Study grants but in countries nearby Seven doctors from different parts of Afghanistan have been awarded fellowships in 2001 to study in neighbouring countries via a longstanding WHO programme. The doctors, who work for and are nominated by the Ministry of Public Health, travel to countries such as Pakistan, Iran, Egypt, Bangladesh and Thailand to participate in post graduate studies in public health, epidemiology and nutrition. Several more are to take up places funded via programmes such as tuberculosis and malaria. Previously fellowships were given to European and American schools of medicine, but since very few of these doctors returned to Afghanistan after completing their studies, WHO now focuses on universities in countries closer by unless there are compelling circumstances. Currently all fellowships have only been awarded to men, but WHO education officer Alexandra Taha says efforts are under way to find acceptable ways of allowing female doctors Training and education All sorts learn about public health Increasingly diverse groups of people are participating in public health training in Afghanistan. While a two month certificate course in district health practice – the sixth such workshop to take place in Afghanistan since 1996 – started in Faizabad this month, earlier this year 18 mullahs from across the country gathered in Jalalabad to attend a week-long training in the principles and planning of basic primary health care. The Faizabad certificate course, originally developed by WHO, the ministries of public 11 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION to participate, including the possibility of distance learning linked to internationally-connected universities in neighbouring countries. “We’re hoping to pilot distance learning next year. If materials are on the Internet, we at WHO could download and get them to the students who could perhaps sit exams either in Pakistan or perhaps via an embassy,” says Ms Taha. region if health authorities agree to set up a facility that is maintained by a librarian and accessible to both men and women. Herat regional health authority was the first to fulfil both these conditions. Health promotion Network of educators needed Handful of female schools reopen WHO has recommended that the MoPH set up a central department for health promotion and a network of regional taskforces to train paramedics and community workers and produce health promotion materials and activities. Last month WHO expert Dr Muzamil Abdelgadar held a 4-day training for 24 doctors to create district focal points for health promotion and a 2-day workshop for the 16 members of a new National Health Promotion core group which it is hoped will be the forerunner of a central department. While receptive to the recommendations, the Ministry of Public Health says they will require external funding to carry them out. WHO and partner agencies including Save the Children UK and CARE are also exploring the possibility of developing a training of trainers package in the methods and principles of health education. Many NGOs and technical health programmes such as the polio campaign and Roll Back Malaria already carry out health education activities in communities, says WHO officer for health education Alexandra Taha, so this group intends to focus on encouraging the development of training, strategic and policy expertise. WHO has also raised the idea of incorporating health education into the school curriculum with the Ministry of Education. Three female schools of nursing are now open in Kandahar, Herat and Helmand, while in Kabul some 65 female student are now re-attending medical school under the supervision of an highly respected female doctor. The nursing schools are enrolling new students as well as those who were unable to complete their studies, but most of the students in Kabul are third year undergraduates who are finishing studies they began before the ban on female studying. New students have not been admitted, due to space constraints, say authorities. But observers say it will be difficult to find new female entrants to take up medicine since none can currently attend high school. WHO is providing books, anatomical models and teaching aids such as photocopiers and overhead and slide projectors to both female and male nursing schools, says Dr Normal, national officer for medical education in Kabul. The three nursing schools are also being supported by the World Food Programme which is providing ‘food for training’ to both tutors who receive very limited and irregular state salaries, and to the students to encourage families to allow their daughters to study. WHO also has funds available to support two Afghan female health trainers for the regional health offices in the two cities. But though regional Ministries of Health have agreed to give the trainers offices in the provincial hospital, so far no suitable applicants have responded to advertisements. Sounds of health About 50% of Afghan population are thought to listen in daily to BBC Afghan service’s radio soap opera “New Home, New Life”. On air since 1994, the programme is, among other things, a vital vehicle for health information and WHO and other UN agencies supports it with story lines, technical advice and funds. In recent episodes, characters have explained many basic and notso-basic health issues including breast feeding, hygiene practices, vaccination and diagnosis of leishmaniasis. It also follows up with a series of books that retell the stories and messages for children and which are distributed free throughout Afghanistan and the refugee camps. WHO donates $50,000 a year, but continued funding is not certain and dedicated extrabudgetary monies are being sought. Pulling in the same direction New nurses, assistant doctors and dentists and pharmacists across Afghanistan now follow the same curriculum for their respective studies. After revision and discussion with WHO, the MoPH and its regional directors last year agreed to implement a newly revised curriculum across all paramedical schools. Now WHO hopes to foster the same idea for trainee doctors in the country’s five medical faculties. The Organisation has also imported medical books and computers to equip a library in each For further information, please contact: Dr Said Salah Youssouf, WHO Afghanistan Representative, Support Office, Islamabad, Ph: +9251 2211224 or 2297931, email: WR@whoafg.org, or Dr Khalid 12 September 2001 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Shibib, Desk Officer Afghanistan, WHO Emergency and Humanitarian Action Department, WHO Geneva. Ph: +41 22 791 2988, email shibibk@who.int. 13 September 2001