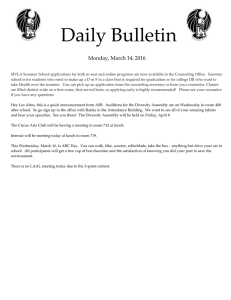

A CASE STUDY ON HIRAM JOHNSON HIGH SCHOOL OPERATION COLLEGE

advertisement