Casey Fox INSC 571 Spring 2015 Fiction Critique

advertisement

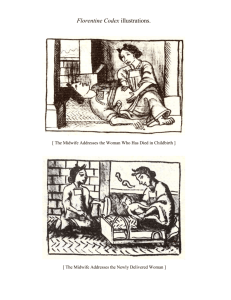

Casey Fox INSC 571 Spring 2015 Fiction Critique Cushman, Karen. The Midwife’s Apprentice. New York: Clarion Books, 1995. Ages 10 and up. Karen Cushman published The Midwife’s Apprentice in 1995 and it subsequently won the 1996 Newbery Medal. The book is small – the hardcover edition is only slightly larger than a mass-market paperback – and slim, coming in at just 122 pages. The bestowal of a major award on a book of this size is generally a testament to the author’s skill at presenting a story in a simple, restrained style, and that is the case with The Midwife’s Apprentice. In a small space, Cushman succeeds in both creating a vivid picture of medieval life and presenting a well-developed heroine who takes an important personal journey. It is an elegant little book, appropriate for older middle-grade readers. The Midwife’s Apprentice is the story of a young girl who lacks a family, a home and even a name. She has no sense of self-worth and her only path is the one that will lead her to a warm place to sleep for the night. She finds herself taken in by a gruff midwife and through a series of ups and downs eventually comes to see herself as an intelligent and worthy human being. Along the way, she interacts with a varied assortment of characters and even manages to acquire what could be called friends. She saves a tortured cat, learns to read and discovers unknown humanity within herself and others. While the story itself is episodic, the heroine’s journey 2 from someone who felt like she did not even deserve a name to a capable young woman progresses deliberately and steadily. Renowned illustrator Trina Schart Hyman provided the original cover art, which introduces the major characters of the book and helps set the tone for the story to come. The style of dress and calligraphic font tell the reader that the book takes place in the Middle Ages, yet there are no knights, castles or fine ladies to be found. A plain girl who appears to be twelve to fourteen years old fixes her intense gaze on the reader from the center of the picture. She wears a wimple and a simple dress, and holds a purple flower delicately in her hands. She looks serious, perhaps unhappy, and is accompanied by a raggedy orange cat. In the background, a house window is open to reveal a scene of childbirth that includes two women, one presumably the midwife referenced in the title. The reader can infer that this will be a story of medieval village life, and that that life is not necessarily an easy one. The Midwife’s Apprentice, however, is not unrelentingly grim. In fact, it offers its fair share of levity, and ends on a happy note. Perhaps the cover could be more effective in conveying a bit of the happiness that our heroine experiences – it is a skillful and evocative illustration, but a bit dour to appeal to young readers. Subsequent editions do use different cover art, so it is possible Clarion Books’ marketing department felt the same way. The world of The Midwife’s Apprentice is a small one. Cushman’s focus is on the lives of the peasantry rather than the noble class, so there is nothing in the book to suggest an exact time period – the characters are more concerned with their dayto-day existence than with any historical events that may be occurring at the same 3 time. Thus, Cushman’s primary concerns with regard to verisimilitude are setting and character behavior, both of which generally feel authentic. With very little exposition or overt description, Cushman paints a vivid picture of life in a medieval village. She introduces the reader to various characters going about their lives: the miller, the bailiff, a merchant, a priest, farmers, maids and laborers. The reader gets a clear sense of the important role each villager plays in the survival of the community. While the language and point of view seem authentic, Cushman does briefly succumb to the temptation of using her main character to act as a vessel for the insertion of modern sensibility. The chapter “The Devil” recounts the villagers’ fear that the Devil has come to cause trouble in their lives. It is revealed to the reader that Alyce herself is the perpetrator of the devilish activities and meant to expose the untoward behaviors of those who had treated her the worst. While amusing, this chapter feels out of place for both the book and the character of Alyce, and is the only time it feels like the author projects a modern perspective onto the story. One of the primary themes in The Midwife’s Apprentice is that of identity: both self-identity and acknowledgement by others. Cushman uses names as the primary way of articulating this theme, particularly the heroine’s. When the story begins, she “knew no home and no mother and no name but Brat and never had” (2). Others regard her as subhuman, and she herself does not question them. She becomes Beetle once Jane the Midwife takes her in, because Jane found her sleeping in a pile of manure like a dung beetle. A beetle is still not a human, and Jane and the other villagers treat Beetle with little regard. In The Midwife’s Apprentice, names 4 impart humanity, and later, after events lead Beetle to realize she is someone who might actually be worth something, she decides she needs a name. A stranger mistakes her for a girl named Alyce, who knows how to read. “Did she then look like someone who could read?” Beetle thinks. Then, “Beetle was no name for a person, no name for someone who looked like she could read” (31). In her newfound confidence, Beetle rechristens herself Alyce, thus taking a major step forward in her personal journey of self-actualization. Convincing others to think of her as Alyce is also an obstacle, but it becomes clear that those to whom she exhibits intelligence, strength and humanity are the ones who readily accept her new name. Will Russet is the first to call her Alyce, but only after she saves him from drowning when no one else would. The young boy whom she helps to secure food and shelter has no problem believing she is Alyce. Jane the Midwife, however, is disdainful when Alyce presents her new identity, saying, “You look more like a Toad or a Weasel or a Mudhen than an Alyce!” (33). Later in the book, however, Alyce and the reader learn that Jane did not think Alyce was stupid, only that she was too easily cowed and lacked the confidence to try again after failure. Alyce possesses a great amount of agency, particularly for a young woman in the Middle Ages. Apart from the aforementioned Devil episode, however, she does not feel like a modern girl placed in a historical setting. Her freedom to decide her own destiny comes from the fact that no one loves or cares about her, thus no one bothers to try to control her. While she has this freedom throughout the book, it is 5 only once she begins to value herself that she understands she can use it to actively create the life she wants. Alyce’s growth throughout The Midwife’s Apprentice is interesting, as it forms a cyclical pattern. She thinks of herself as worthless because others do, but any time she receives a kind word from someone, she wonders if what they say could actually be true. When a merchant alludes that she could be an attractive young woman, Cushman describes his words as “gifts”, that “nestled into Beetle’s heart and stayed there” (30). Kindness from a scholar gives her the confidence to learn to read, and she returns to the memory of a warm conversation with Will Russet for weeks after it happened. These thoughts giver her confidence and, in turn, this confidence leads to even greater acceptance by those around her. The Midwife’s Apprentice is an elegant story of self-actualization that will appeal to young readers who are just beginning to think seriously about who they are. The medieval world Cushman presents is atmospheric, yet not foreign enough to alienate young readers, and Alyce is a strong model of agency who can help children see that their potential for success may be waiting for them to discover just below the surface.