How often will ovarian preservation result in reoperation? Gilbert Sayegh MD

advertisement

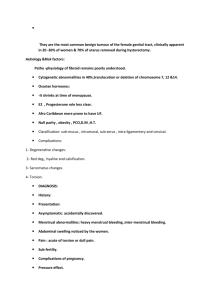

How often will ovarian preservation result in reoperation? Gilbert Sayegh MD Cornelia DeRiese MD BACKGROUND Approximately 78% of women between the ages of 45-64 years have prophylactic oophorectomy when hysterectomy is perfomed for benign disease. [15] According to the CDC, thera are approximaltely 600,000 hysterectomies performed yearly in the U.S., 51% of them include bilateral oophorectomy. Literature quotes 7.6% re-op rates to have ovaries removed at a later date. [13] Most of these repeat surgical procedures are performed due to pelvic pain or pelvic mass. Many re-op occur within 5 years of the hysterectomy. [13] Women with endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and chronic pelvic pain are at higher risk of reoperation if ovaries are retained. [13] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has advised that the decision to perform a prophylactic oophorectomy during hysterectomy should be individualized, based upon factors such as loss of ovarian function and the risk of future ovarian surgery if the organs are retained. [13] CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS Prior to performing elective oophorectomy the following factors should be considered: Age Genetic risk of ovarian cancer Atherosclerosis Osteoporosis Heart disease ADVANTAGES OF PROPHYLACTIC OOPHORECTOMY Reduction in risk of developing ovarian cancer Incidence 1.7% Reduction in risk of developing breast cancer [7] Relief of bothersome symptoms causing chronic pelvic pain. DISADVANTAGES OF PROPHYLACTIC OOPHORECTOMY Surgical menopause Loss of natural ovarian hormones When compliance with estrogen therapy is assumed to be perfect, oophorectomy yields longer life expectancy than retaining the ovaries. [7] Increase in risk of cardiovascular disease [1,2,7] Oophorectomy after age of 50 increases risk of developping an MI by 40% [15] Increase in risk of osteoporosis Oophorectomy after age 40 increases risk of hip fx by 50% [11] Increase in risk of neurologic impairments: Cognitive impairment affecting short term memory and general dementia. [11] Parkinson’s [11] Adverse occular changes Decline in psychological well being [5] Irritability, mood swings Hot flushes Adverse skin and body composition changes Decline in sexual function Vaginal dryness OBJECTIVE There are no West Texas studies evaluating the re-op rate for ovarian disease after hysterectomy. Our objective is to collect and interpret data from our institution in order to be able to more appropriately counsel patients who have to undergo a hysterectomy for benign indications about the pros and cons of elective oophorectomy. This will include the risks and benefits, morbidity and mortality of reoperation and we also want to look at excess expenses. DESIGN Retrospective chart review of patients who undergone a hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy, and oophorectomy by itself. MATERIALS AND METHODS Chart review of subjects who underwent hysterectomies at UMC from 1993 to present. Using dictated operative reports, we will collect data on reason for the procedure and type of hysterectomy and whether ovaries were left behind or removed. We will also collect data on subjects who returned at a later date for a separate procedure to remove ovaries. Subjects who underwent oophorectomies will be evaluated to see if they had previous hysterectomies. WHAT RESULTS ARE WE LOOKING TO FIND? Reoperation rate within our patient population. Between 1993 and present, there were 3251 hysterectomies performed at UMC. During the same time there were 1586 oophorectomies performed. The data will be stratified by: Age groups Indications for the hysterectomy Mode of surgery. RESULTS CONT’D As additional information for the cost analysis, we will look to see if there were any complications including: • • • • Wound infections Bleeding Damage to major organs Any other reason that prolonged hospital stay. Conclusion Hysterectomy is the second most frequently performed major surgical procedure for women of reproductive age in the United States. During 2000–2004 the overall hysterectomy rate for the U.S was 5.4. per 1,000 women. Highest among women between ages 40-44 years old. 38% of women between the ages of 18-44 years old have concurrent oophorectomy with their hysterectomy 78% of women between the ages of 44-64 years old have concurrent oophorectomy with their hysterectomy The overall hysterectomy rate for women living in the South was 6.5 per 1,000 The three conditions that make up 90% of all hysterectomies were uterine leiomyoma ("fibroid tumors"), endometriosis, and uterine prolapse. CONCLUSION CONT’D Looking at cost Average cost for hysterectomy with or without BSO is in the range of $24003700 depending on the type of surgery being performed. • This is only the cost of the surgery Oophorectomy alone is ---------- Hospital stay is $2000 per day Anesthesia is $2000 per case Pathology is $600-1000 per specimen CONCLUSION CONT’D Dr Parker et al designed a model to study the major risks and benefits related to the decision to have prophylactic bilateral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease in women who have average risk of ovarian cancer. Results: • Women younger than 65 y.o. clearly benefit from ovarian conservation and at no age is there clear benefit from oophorectomy. • He concluded that women younger than 65 had increase risk • Dying from heart disease • Women choosing ovarian conservation at ages 50-54, there is 8.5% survival advantage measured at age 80 compared with the oophorectomy group. • Increase mortality from hip fractures. • Pt who were followed to a median of 15 years who were postmenopausal at the time of oophorectomy had 54% more osteoporotic fractures than women with intact ovaries. • His argument is that postmenopausal ovaries continue to secrete small amounts of estrogen for years. Ovaries have also shown to secrete significant amount of testosterone and androstenedione which is converted to estradiol and estrone in muscle and fat. Another study that looked at 121700 women determined that oophorectomy between age 40-44 years old doubled the risk of MI compared to women with intact ovaries. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Shoupe D, Parker WH et al. Elective oophorectomy for benign gyn. Disorder. Menopause. 2007;may-jun; 14 Parker WH, Shoupe D et al. elective oophorectomy in gyn patients. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007 aug;19(4) Bhavnani V, Clarke A. Women awaiting hysterectomy: a qualitative study of issues involved in decision about oopherectomy. BJOG. 2003 Feb;110(2): 168-74 Fry A, Busby-Earle C et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy versus screening. Psychooncology. 2001 May-Jun; 10(03): 231-41 Fong YF, Lim FK et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy: a continuing controversy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998 Aug; 53(8): 493-9 Das N, Kay VJ, et al. Current knowledge of risks and benefits of prophylactic oopherectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003; 109(1): 76-79 Speroff T, Dawson NV et al. A risk benefit analysis of elective bilateral oophorectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jan; 164 Garcia CR, Cutler WB. Preservation of the ovary: a reevaluation. Fertil Steril. 1984 Oct; 42(4) Suchaartwatnachai C, Jetsawangsri T et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy of benign uterine disease in premenopausal women: 11 years review. J Med Assoc Thai. 1994 Oct; 77(10) Farquhar CM, Harvey SA et al. a prospective study of 3 years of outcomes after hysterectomy with and without oopherectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194 Moscucci O, Clarke A. prophylactic oophorectomy: a historical perspective. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007 Mar; 61(3): 182-4 Rocca WA, Bower JH, et al. increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oopherectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007; 69(11): 1074-83 ACOG Practice Bulletin. Elective and risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Clinical management guidelines for OBGYN. Number 89, Jan 2008 Walter AR, Brandon RG et al. Survival patterns after oophorectomy in premenopausal women: a populationbased cohort study. The lancet oncology. 2006;7(10) Parker WH, Broder MS, et al. Ovarian Conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Clinical Obstet & Gynecol. 2007.50(2)