BREATHE, AND OTHER STORIES OF THAT NATURE Brett Alan Wallis

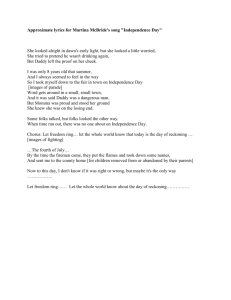

advertisement