Document 16126354

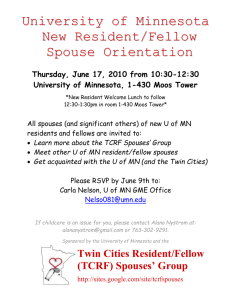

advertisement