Enterprise Registered Training Organisations: Their operations, contributions and challenges Project summary

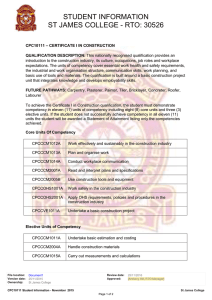

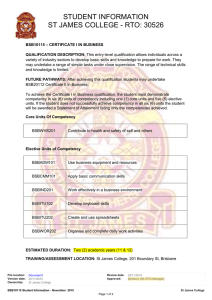

advertisement