FOR PEERS OR PEER TUTORS RESPONDING TO DRAFTS

advertisement

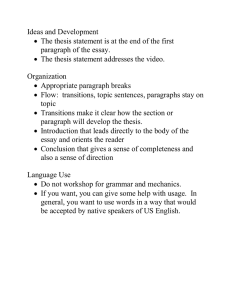

FOR PEERS OR PEER TUTORS RESPONDING TO DRAFTS Recent research indicates that student writers react best to teacher comments that are specific, elaborated, give useful advice, and are framed as open-ended questions (Richard Straub, “Students’ Reactions to Teacher Comments,” Research in the Teaching of English, February, 1997). In responding to your peers’ writing, try to transform the textbook words of wisdom below into revision-provoking questions. TITLES 1. Titles should be both interesting and informative 2. Titles should begin the process of focusing a reader's attention on the point of the piece, and even prick the reader’s curiosity a bit. 3. Sometimes titles come early to mind as you’re writing. Sometimes the piece is finished and ready to hand in, and you still can’t come up with a title. Try rereading your final paragraph. Sometimes a word or phrase from the conclusion will work. Or look for a recurring image or motif in your work; a “found metaphor” can make an effective title. INTRODUCTIONS 1. An opening paragraph should raise your readers’ interest, grab their minds and rivet them on your ideas. 2. An opening should provide a context for your discussion, a reason why somebody would want to clear out some space in his or her busy life to read your piece. 3. Once you have your reader’s attention, the last sentence(s) of an introduction should focus your reader on the thesis of your piece, the one point you will make, the argument you will prove. THESIS STATEMENTS 1. Try to get your thesis made in one sentence. It’s the hardest sentence in the whole piece to write. It tells your reader what point you are proving, how your are proving it, and why. 2. Be specific in your thesis, and don’t belabor the obvious – give it an argumentative edge. 3. As you begin to write you might not be sure enough of your subject to formulate a good, specific, one-sentence thesis. That’s ok. Try a trial thesis, the best guess you can make at the moment. Then as you write, keep coming back to it, improving it as you go on and become more sure. BACKGROUND PARAGRAPHS 1. Sometimes before your readers are ready to launch from your thesis into the body of your argument, they need some backgrounding. It might be historical background, or a set of definitions for important terms. If you are arguing one side of an issue, your readers might need to hear the others side first, briefly, just to be assured you considered it. BODY PARAGRAPHS 1. What’s the one idea being raised, focused on, and proved in this paragraph? 2. Just as the thesis statement formulates the argument of the whole piece, so a topic sentence, usually the first sentence of each body paragraph, formulates the argument of each paragraph. 3. Paragraphs prove their points by reporting evidence (data, quotations, descriptions, etc.) and analyzing , explaining exactly how that evidence supports the point 4. Paragraph development: Take a stand. Offer evidence. Explain how the evidence supports the stand. Take another stand. Offer more evidence. Explain how…. 5. Be sure your evidence is cited accurately and that credit is given to your sources FLOW 1. Readers should move from the central idea of one paragraph to the central idea of the next without getting lost, without making huge mental leaps. 2. Transition devices at the beginnings of paragraphs help remind readers of the connections between ideas they have read and the new ideas they are about to read. 3. Readers should sense each paragraph building on the ideas of the previous paragraphs. They should feel they are getting somewhere in an essay. They should enjoy the experience. TONE 1. 2. 3. 4. The tone of the essay should be appropriate to the subject. Use technical terms accurately. The best sentences are concise, clear, emphatic. Are any of the words unnecessary? Does it ever take 5 words to say what 2 well chosen words might say better? 5. Your verbs should be working for you. Omit bland “to be” verbs. 6. Correct spelling and punctuation 7. Vary the lengths and types of sentences you use. Sentences need not always begin with the subject. CONCLUSIONS 1. Close up your argument without closing your readers’ minds on the subject. 2. Avoid circling back to repeat the thesis as a strategy for closing an essay. Assume that both reader and writer have learned something, and are now ready to engage the implications of the thesis.