HIV RISK REDUCTION INTERVENTIONS IN POPULATIONS WITH SERIOUS

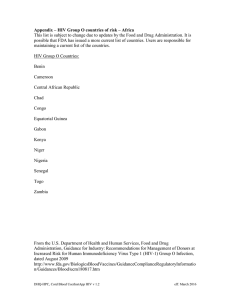

advertisement